I am a huge fan of the software-as-a-service (SaaS) model, both as a software creator and as a software consumer.

It’s how I earn a living. My company makes DevResults, a SaaS product for a very niche market (monitoring and evaluation for foreign aid programs). Our software addresses a real need, more effectively and more cheaply than the in-house custom databases that used to be the only option.

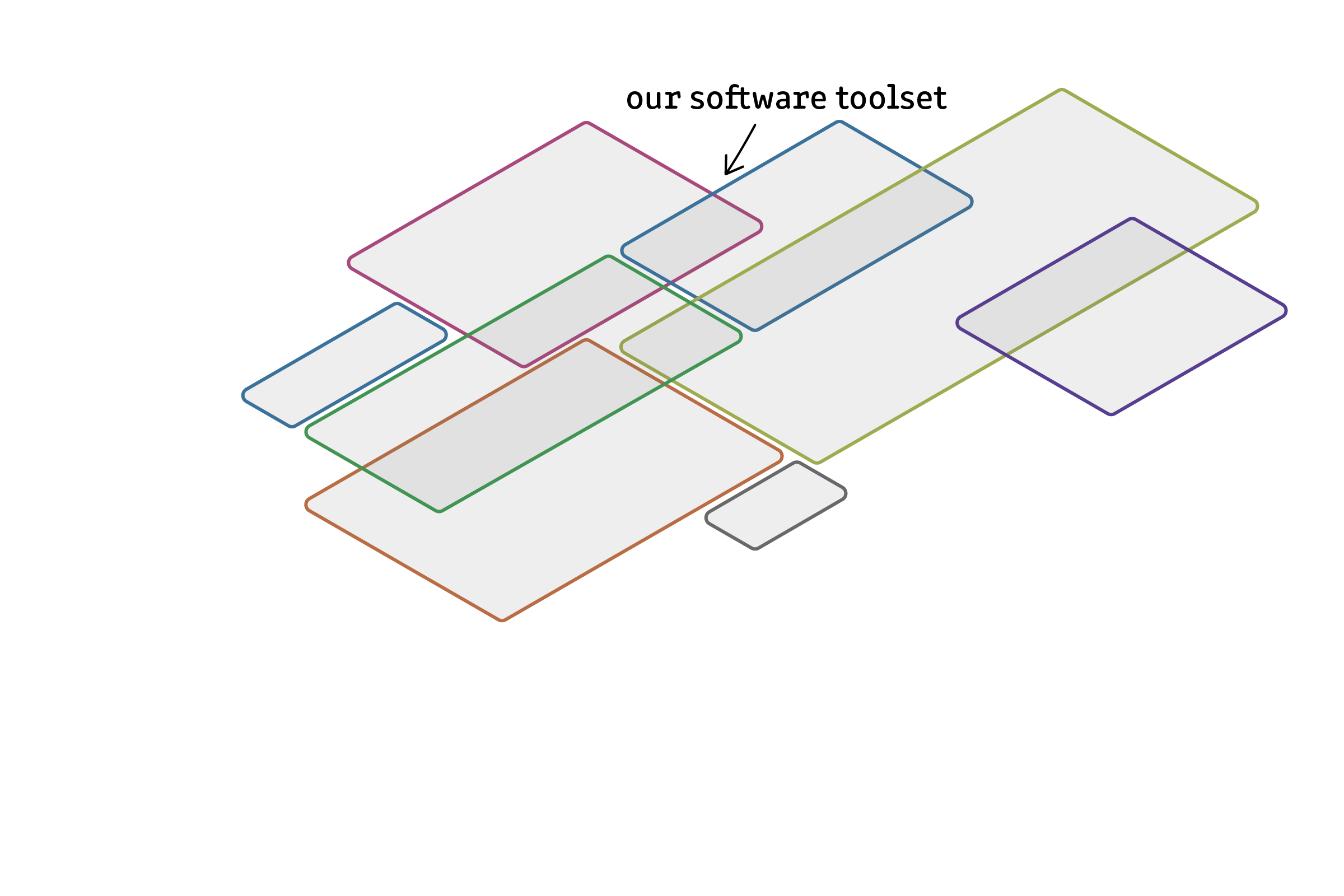

And SaaS is how my team is able to collaborate closely even though we’re scattered all over the globe. We couldn’t do what we do without our toolset of web-based apps, which includes G Suite, QuickBooks Online, Zoom, Slack, GitHub, Asana, FreshDesk, FreshSales, Backblaze, Expensify, Headway, Knowledge Owl, and more.

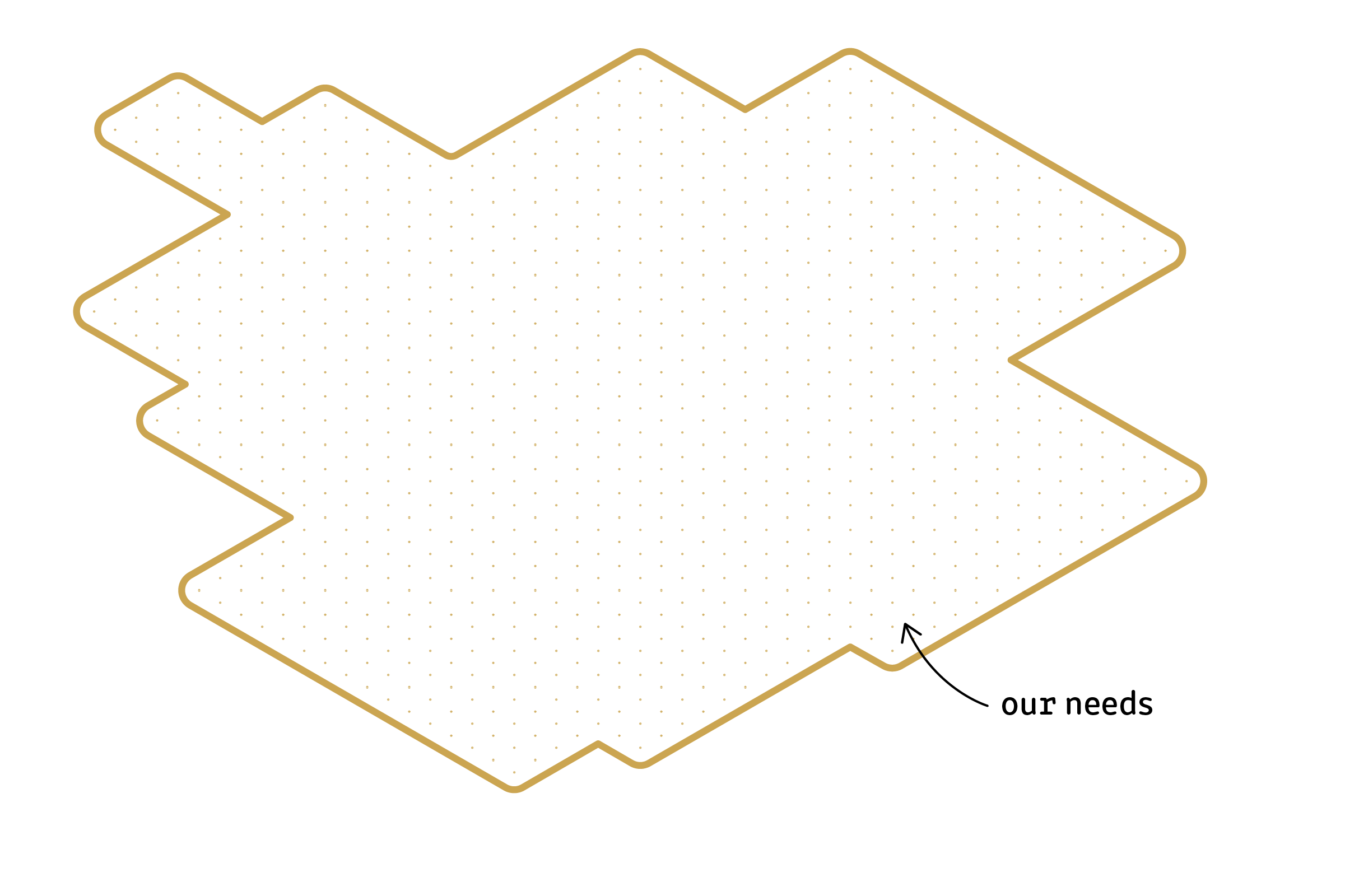

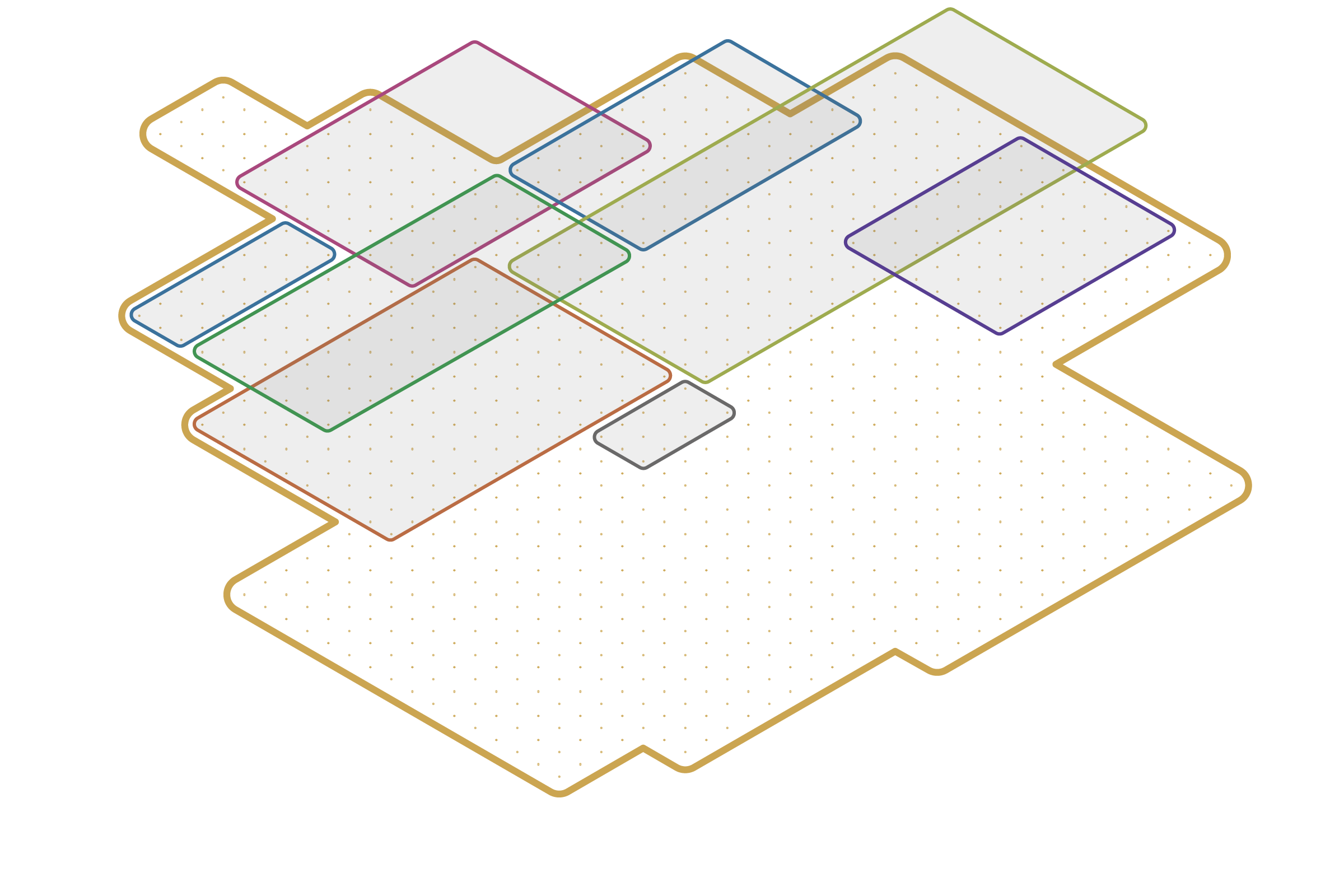

But our toolset still falls frustratingly short. We have too many different tools that, for the most part, don’t talk to each other. Every tool comes with its own implicit worldview, which you can either adopt or spend your life fighting against. And we have needs that aren’t met at all, because they’re too specific to our situation.

So this is how we work. Lots of different tools that kind of fit our needs, but not really; and big areas where we just make do.

Large organizations solve these problems with big, expensive, heavily customized implementations of enterprise software suites. (At least I think they do! I’m not really sure how well that works in practice.)

But small businesses, little nonprofits, and teams within larger organizations know what I’m talking about. DevResults’ customers know what I’m talking about. We all have problems that should be solved by software, but aren’t.

The trouble with commercial software

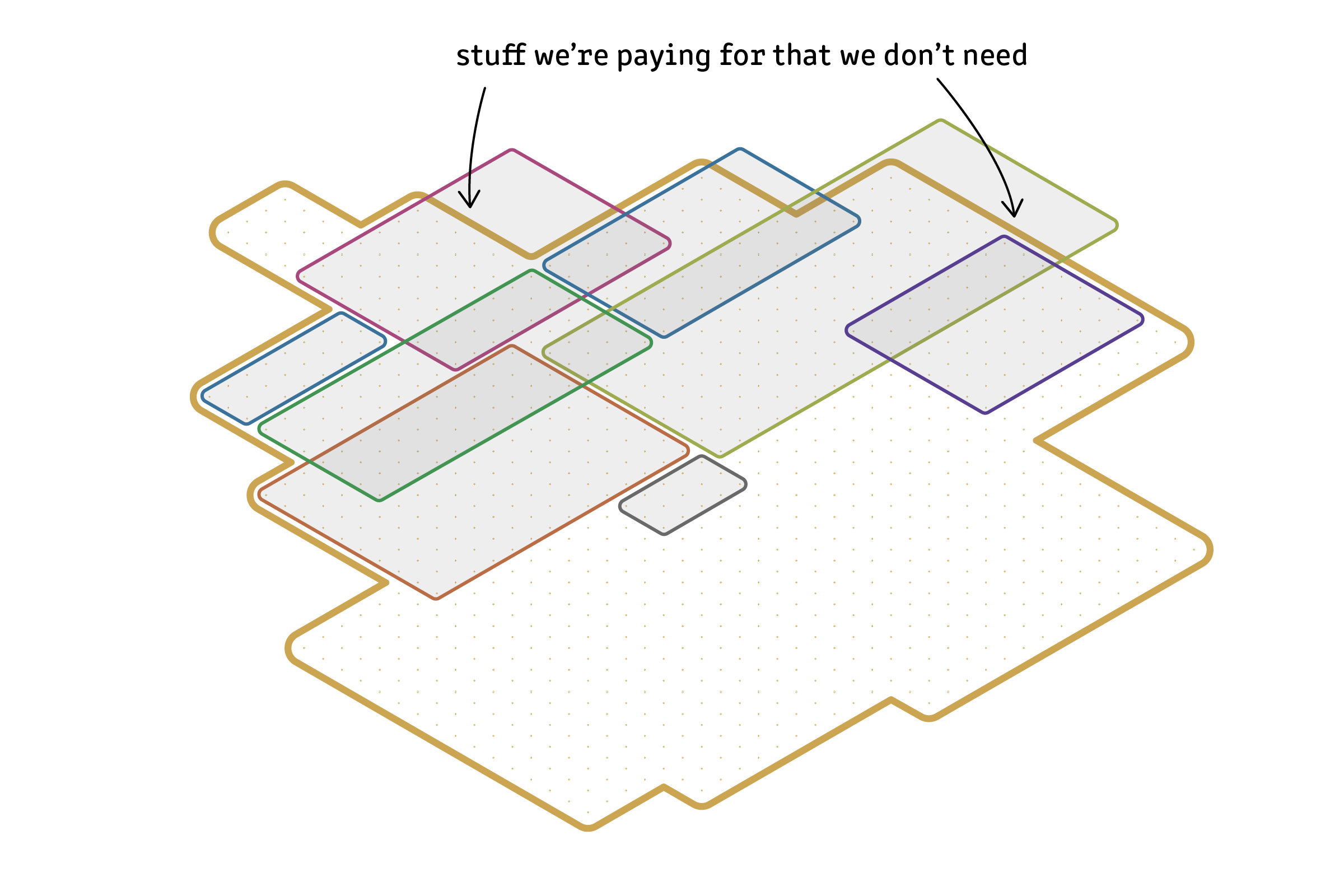

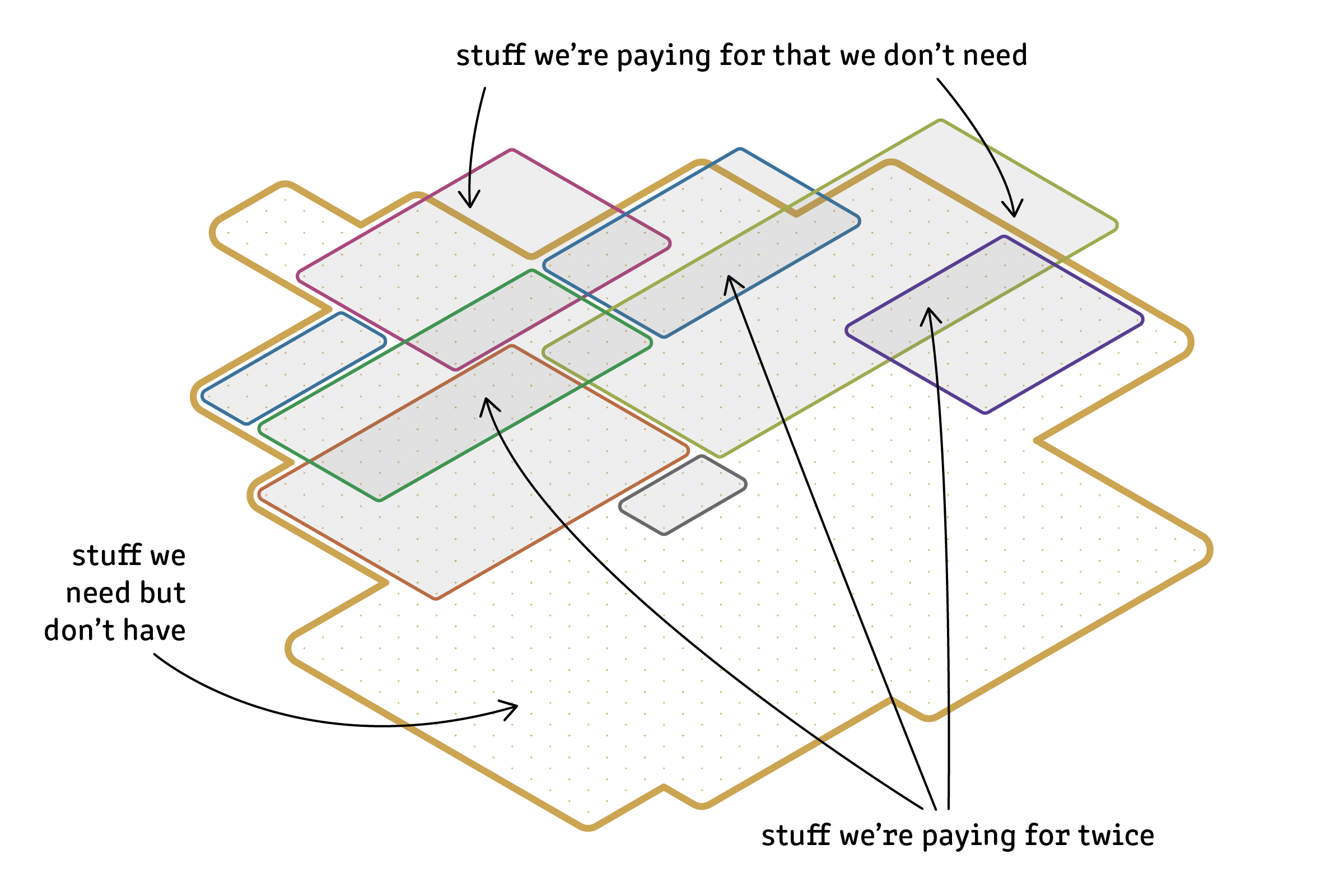

The problem has three parts to it:

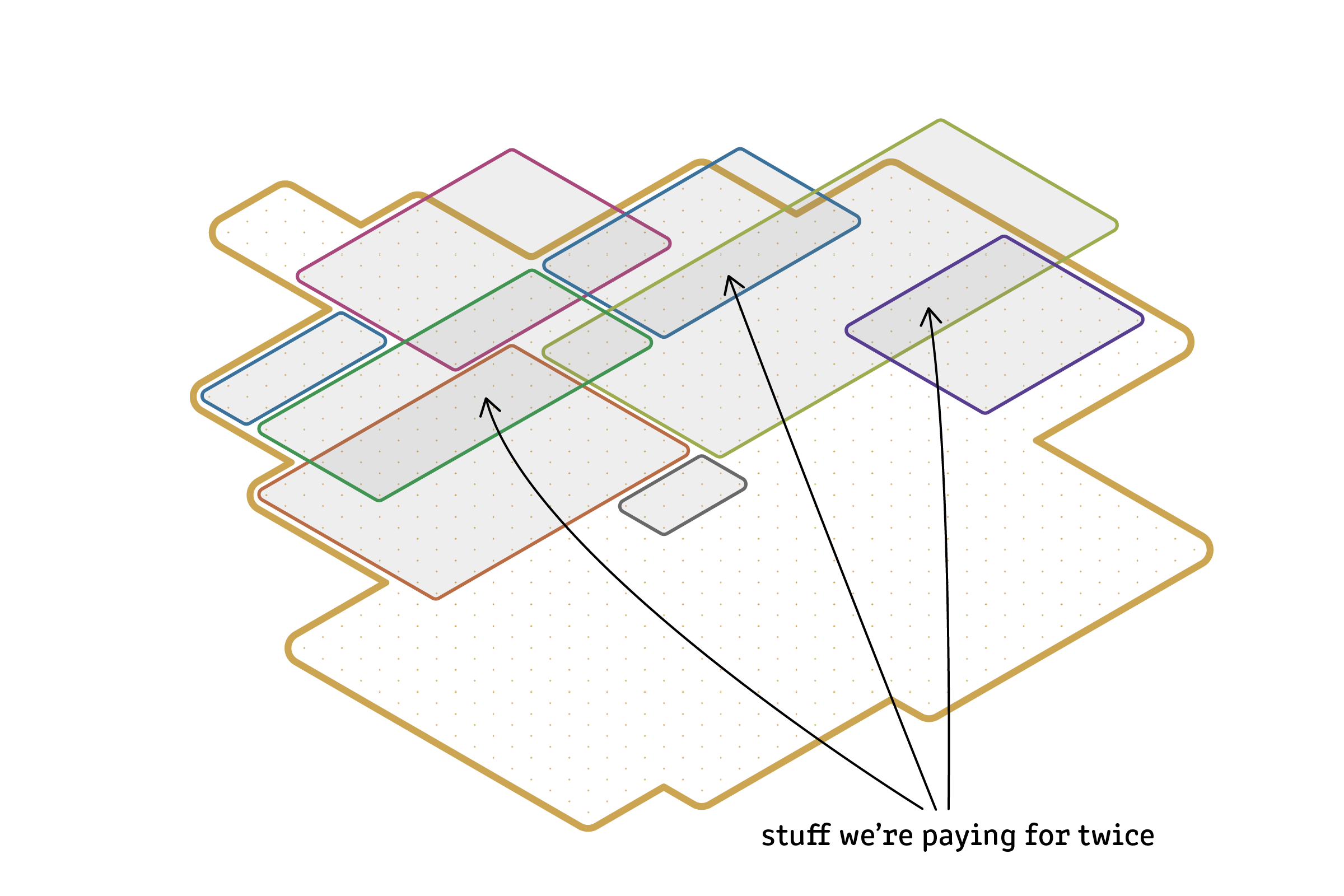

- There’s lots of duplication and overlap between applications.

- We’re paying for lots of stuff we don’t use.

- There are still gaps that we have to cover with home-made systems.

Let’s look at each of these in turn:

1. There’s lots of duplication and overlap between applications.

Sometimes it feels like my team uses a ridiculous number of products with overlapping footprints.

- Customers are explicitly represented in our CRM system (FreshSales), in our accounting system (QuickBooks), and in our help desk system (FreshDesk).

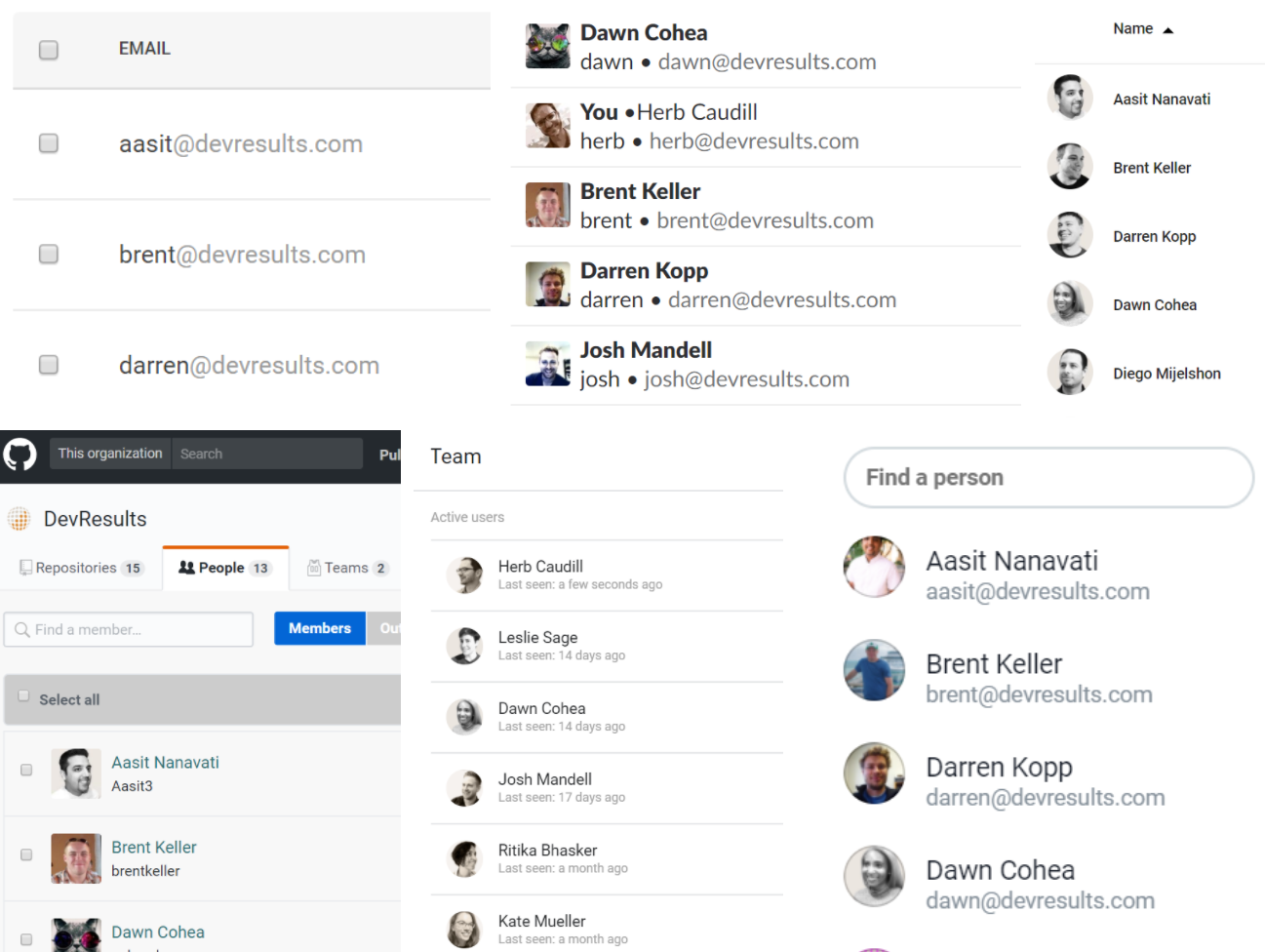

- Teams are explicitly represented in our source control system (GitHub), our project management system (Asana), and our central identity management system (Azure AD).

- Tasks are explicitly represented in Asana, FreshSales, FreshDesk, and GitHub.

- Conversations between team members can happen in GitHub, in Slack, in FreshSales, or in Asana.

- Files might be found in Slack, Asana, FreshSales, FreshDesk, or Google Drive.

This duplication is a problem: For one thing, we’re paying twice (or three or four times) for these features.

It’s not just the expense: Duplicate features add to everyone’s cognitive burden. It’s not clear where some things belong. Do software development tasks go in Asana, which is what we use for managing other projects and tasks? Or do they go in GitHub Issues, which is optimized for that purpose? Either way we have to make rules.

But the bigger issue is that we don’t have a single source of truth for lots of things. In many cases we just have to maintain multiple, parallel lists in different places, with all the repetitive work, human error, and lack of clarity that comes with that.

2. We’re paying for lots of stuff that we don’t use.

There are big areas of unused functionality in every tool that we just ignore. For example:

- FreshSales: Territories, lead scoring, in-app calling

- Asana: Conversations, progress dashboards

- FreshDesk: Forums

These are often great features in their own right, that a bunch of smart people spent a lot of time building. But for whatever reason, we don’t need them: Maybe we don’t have the problem they solve. Maybe we’ve solved those problems some other way. Either way we’re paying for something that we don’t use.

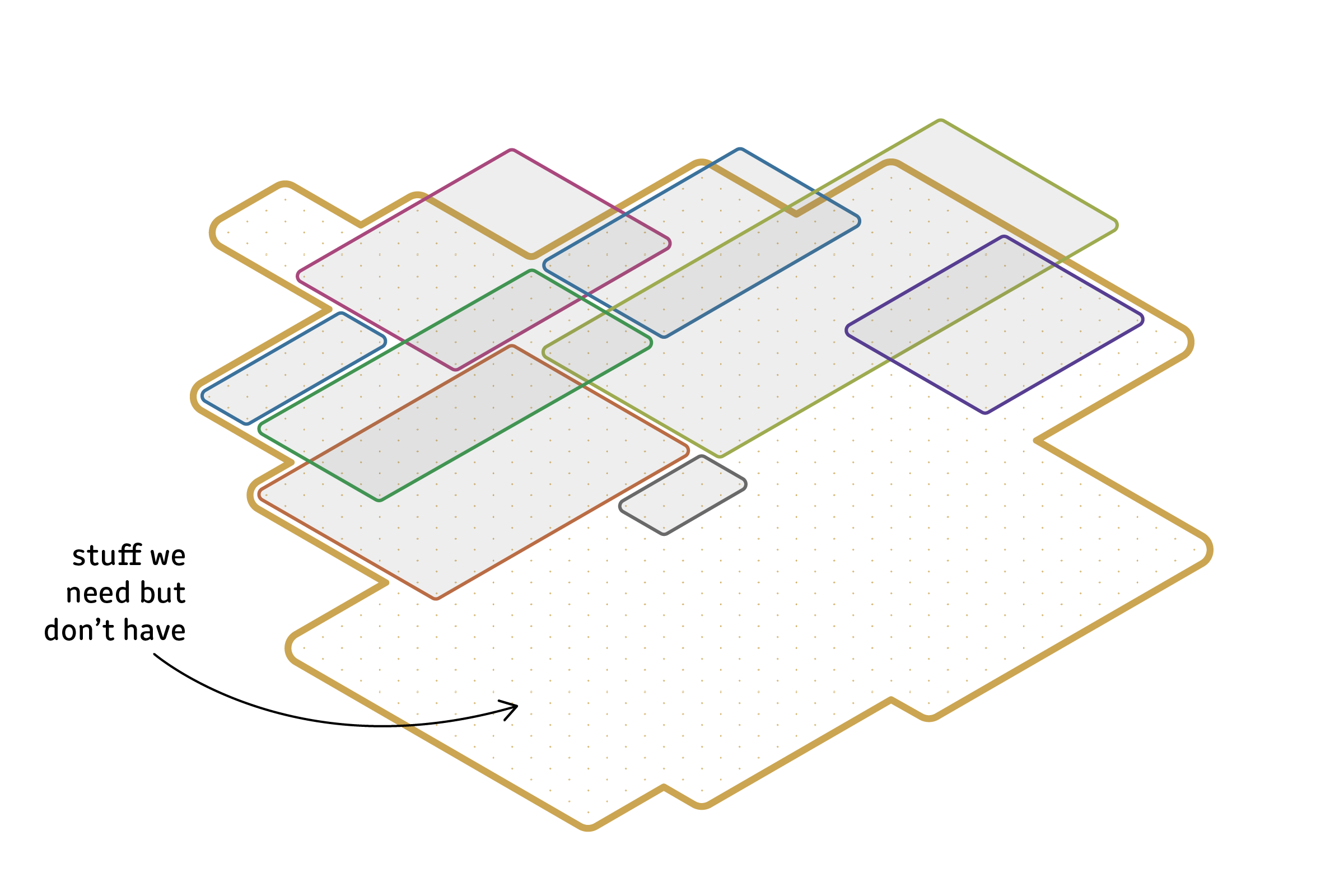

3. There are still gaps that we have to cover with home-made systems.

Finally, there are still important gaps — parts of our team model that aren’t represented by any of these tools.

So for example we don’t have a definitive list of ongoing projects or teams anywhere.

There’s also a lot of vital information about customers and instances that we don’t have a good place for. We have one spreadsheet where we keep track of when it’s time to bill each customer for their annual subscription. We have another where we keep background information on individual projects using our software, for support purposes — notes about contacts, how they’re using specific features, etc.

I could go on. We have a spreadsheet for cash planning and another to keep track of debts and payments. In order to get an overview of the company’s financial health going forward, I’ve cobbled something together that pulls numbers from QuickBooks, FreshSales, and from other spreadsheets. This gives me a janky dashboard that is currently broken because a Zapier task stopped running for a couple of months.

So that’s where we are. It’s a bit of a mess.

We’ve pieced together a bunch of apps to try and capture all of our work, and it’s simultaneously too much and not enough.

It’s a lot for a new employee to figure out: I recently spent a couple of days just documenting on our wiki how everything fits together. Even people who have been here a long time aren’t always sure where to start a conversation, where to share a document, or where to record an important fact about a customer.

Systems fatigue is real.

Any time anyone suggests a new tool to the team (usually me!) there’s an audible sigh — even if it covers a gap we know we have. Really? Another system to figure out, with its own username and password and its own UI quirks and its own place to upload your avatar? Another system to provision or deprovision when people come and go?

The SaaS ecosystem is amazing — if you think of a problem, you can almost certainly find a product out there that addresses it, for $1 or $25 or $100 per user per month. But realistically you can only have so many different systems. Not just because those subscription costs start adding up, but also because the indirect costs — the staff time required to administer them and the cognitive burden of learning and thinking about them — start adding up.

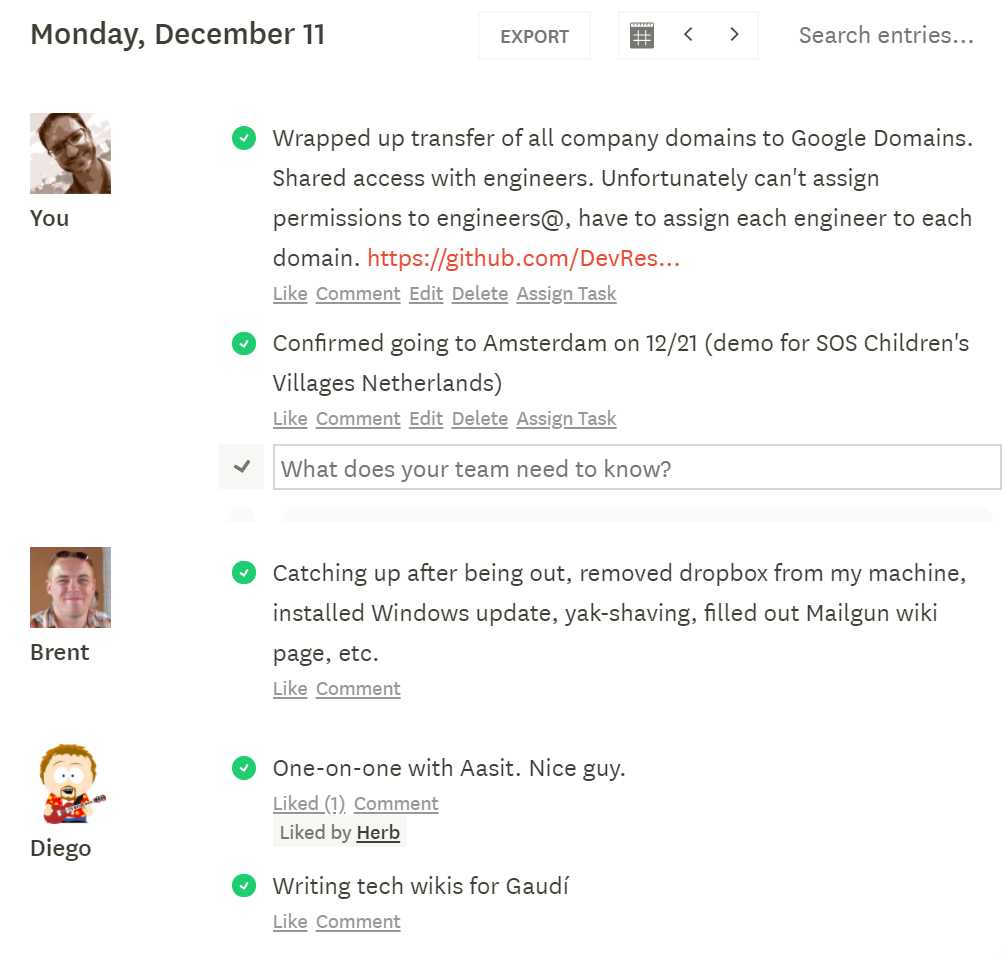

iDoneThis does one thing well. But is it worth $1200/year, plus the cognitive and administrative burden of having Yet Another System?

Consider the case of iDoneThis, a little single-purpose service that provides each team member a place to say what they got done every day.

It’s such a simple thing, but makes our weekly meetings a lot shorter because we don’t have to go around asking people what they’ve done. So it provides real value to our team! But it’s a perennial candidate for the chopping block. Our plan costs $9 per user per month, so about $1,200 per year — not a lot of money, but not nothing either. And it’s such a trivial app — couldn’t it be replaced with just a Slack channel? Or a spreadsheet? Or a Google Doc?

We’re part of the problem too!

Our customers’ experience with our SaaS product gives another perspective on the same set of problems. I see our customers struggling with DevResults in the same ways we struggle with our toolset:

- Trying to figure out what in their organizational model maps to a DevResults “activity”.

- Using tags to make up for the lack of custom fields.

- Ignoring entire sections of the app because they solve problems that don’t have, or that they’ve solved elsewhere.

- Persuading users to learn to use yet another system.

- Wondering how DevResults fits in with other tools they use: When it has duplicate functionality, which to use? How to sync up with information that lives elsewhere?

Two trade-offs and two failed promises

Let’s take a look at two big trade-offs you face when putting together a software toolkit for a team:

Trade-off 1: Minimizing the number of systems vs. using the best tool for the job.

If you go the first route and try to use as few systems as possible, you end up with sprawling multi-purpose software that does a half-ass job at lots of things.

If you go the second route and try to use the best system for each need, you end up with a hive of unconnected single-purpose tools.

In theory, this trade-off can be avoided by integration. If your systems talk to each other, it’s not as much of a problem to have lots of focused single-task apps. Along the same lines, if you can get single sign-on working, people don’t have to keep track of lots of different passwords; and if you can get automated provisioning and deprovisioning working, then you don’t have to maintain duplicative lists of users in each system.

In reality, integration turns out to be too hard to get working for most small teams and organizations.

The failed promise of integration

Some systems have built-in integrations. Slack, for example, advertises hundreds of integrations. In practice, this mostly just means that you can send an app’s notifications to Slack channels.

Slack “integration” with Google Drive: 🙄 Meh.

Other built-in integrations turn out to be pretty lame when examined closely. Asana and Slack both “integrate” with file storage services like Dropbox and Google Drive. In practice, this just means that Asana and Slack both have a clumsy built-in file picker for sharing files directly from your cloud storage. It’s easier to just drag and drop files from your local file system.

Often it’s attractive to buy into a suite, or use multiple products from the same vendor, precisely because they promise to fit better together. That was the deciding factor for us in adopting FreshSales as a CRM — we were already using FreshDesk for support tickets, and we hoped to smoothly consolidate contact data and interaction history from before the sale (CRM) and after the sale (help desk). In practice, this was nearly as awkward as if we were working with completely unrelated products.

Zapier lets you link one app to another via their public APIs: A trigger in one app results in an action in another. In some simple cases it works great. But the trigger/action model can be clumsy and brittle in practice. Getting two systems to maintain the same dataset in sync is a real challenge. Sometimes it just fails silently, and you don’t realize it until you go to look at your home-made dashboard and it doesn’t have any data for the last couple of months.

Trade-off 2: Using generic off-the-shelf tools vs. creating custom solutions.

Commercially available software gives you a high level of quality for your money, but you have to make do with a model that only approximates your world.

A custom solution is usually going to be a little lame: In most cases, these solutions are just spreadsheets; but even if you have an in-house development team you’re not likely to match the level of polish and robustness of a commercial product.

In theory, this trade-off can be avoided by customizability. If you can use a well-tested, off-the-shelf system, but then configure it to meet your needs, you have the best of both worlds.

In reality, customizability never goes far enough.

The failed promise of customizability

In some cases we can add custom fields to capture our needs, and maybe change the order of fields on a form. But we always very quickly bump into the limitations of customizability.

- We’ve added a bunch of custom fields to FreshSales, but different people are interested in different things. The biznass tribe is interested in pre-sale information; the support tribe is interested in fields that won’t be populated until post-sale. There’s no way to show different forms to different teams.

- Asana has per-project custom fields, which we sometimes use to assign time estimates and priority levels. But there’s no way to get a global view of these; and they don’t show up at all in individual task lists.

Deconstructing the typical SaaS app

What would a solution to this problem look like? Let’s start by thinking about how the value of a typical SaaS application breaks down:

- The most valuable part of an application is its superpowers — unique features that would be difficult to replicate.

- The core value of the application lies in its domain-specific data model combined with superpowers.

- A layer of infrastructure has to be there for things like managing users and authenticating them.

- Me-too features are tacked onto the app in an attempt to turn it into a one-stop shop.

- Customizability and integration are weakly-implemented afterthoughts.

1. A domain-specific data model

This is where an app captures its understanding of a domain.

- Quickbooks models a company’s finances: customers, vendors, transactions, accounts.

- FreshSales models a team’s sales process: reps, leads, deals, accounts.

- FreshDesk models a team’s support process: agents, customers, tickets.

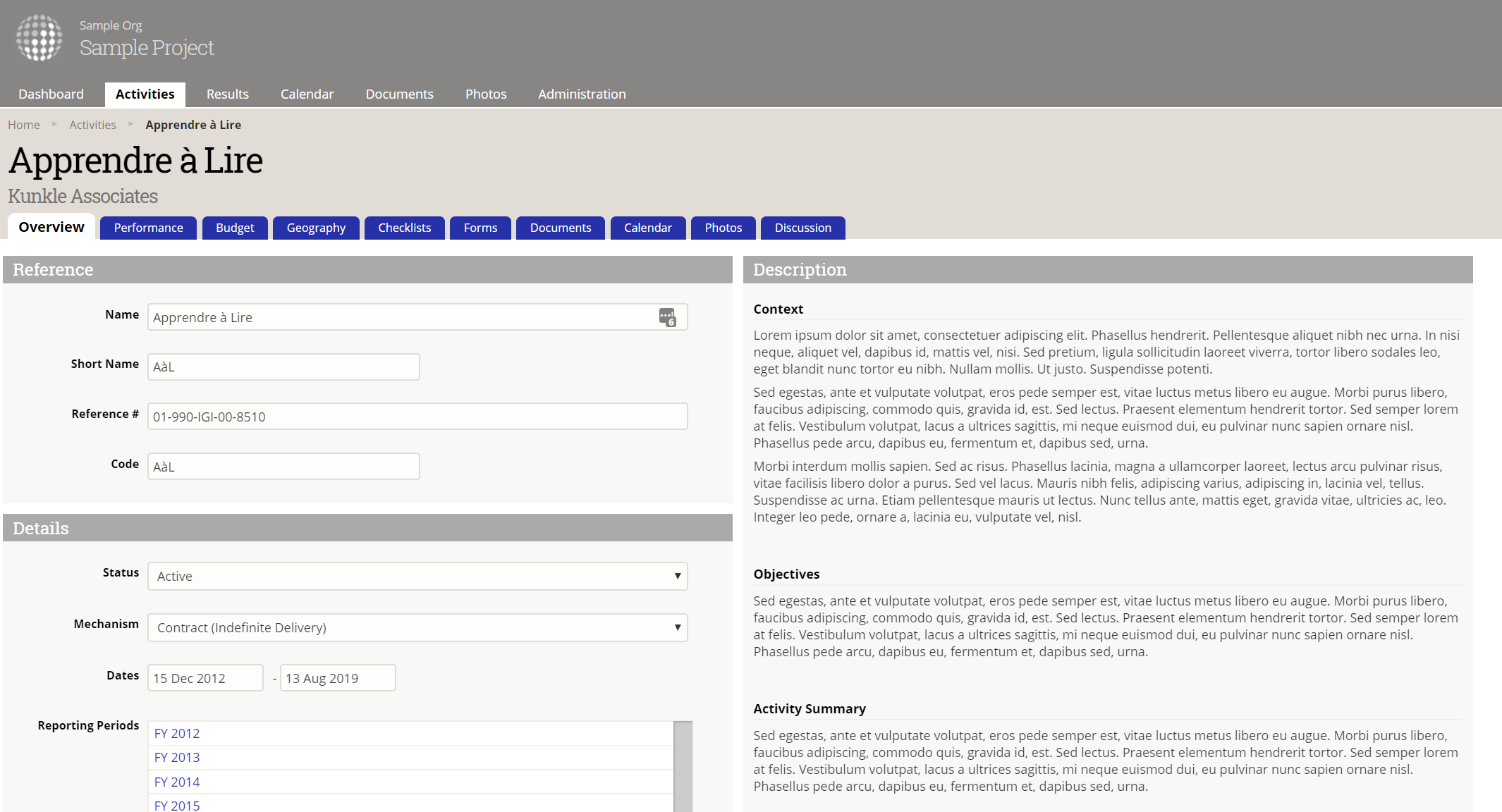

- DevResults models an international development program: activities, indicators, results frameworks, locations.

- Asana models an organization’s work: people, teams, tasks, projects.

FreshSales has a data model that captures a “typical” real-world sales process. A deal (shown here) has a name, a dollar amount, an expected close date, and a probability. It lives in one stage of several that I can define. It’s associated with one account, one sales rep, and one or more contacts. This model may or may not exactly match the way we work; either way it’s not rocket science.

There’s nothing technically difficult about this part: These are just database tables in a relational schema, plus a web UI for browsing and editing records. The web UI piece is not totally trivial, and some do it better than others. Still, it’s a problem that’s been solved thousands of times over.

Some products understand their customers better than others, so they have models that feel more natural. So this can be a differentiator, especially if the product is aimed at a niche market.

Still, even if a software company really understands its domain, the data model still just maps to an ideal or generic domain, and every team and every organization is different. So even at best, the data model only approximately matches your real-world needs.

2. Superpowers

These are the non-trivial skills that set the app apart.

- For GitHub, it’s the git hosting plus UI and workflow around the repositories.

- For Expensify, it’s parsing invoices and receipts.

- For FreshDesk, it’s allowing multiple people to collaborate on triaging a support email inbox.

- For Trello, it’s a well-implemented and unique user interface. (Was unique, anyway! It’s been copied everywhere from Asana to GitHub.)

- For Dropbox and Google Drive, it’s document storage and syncing.

- For Slack, it’s team chat.

Expensify‘s superpower is called “SmartScan”. Drag and drop an invoice or a receipt, and it magically pulls out the vendor, date, and amount. I don’t know if they do it with people or with machines, but either way it would be pretty hard to reproduce this feature!

Not every app has a superpower! Some apps’ value is all in the way they’ve successfully modeled their domain’s data.

3. Me-too features

These are things that go outside of an app’s core strengths.

- Github, FreshSales, and FreshDesk (and DevResults) have some form of task lists.

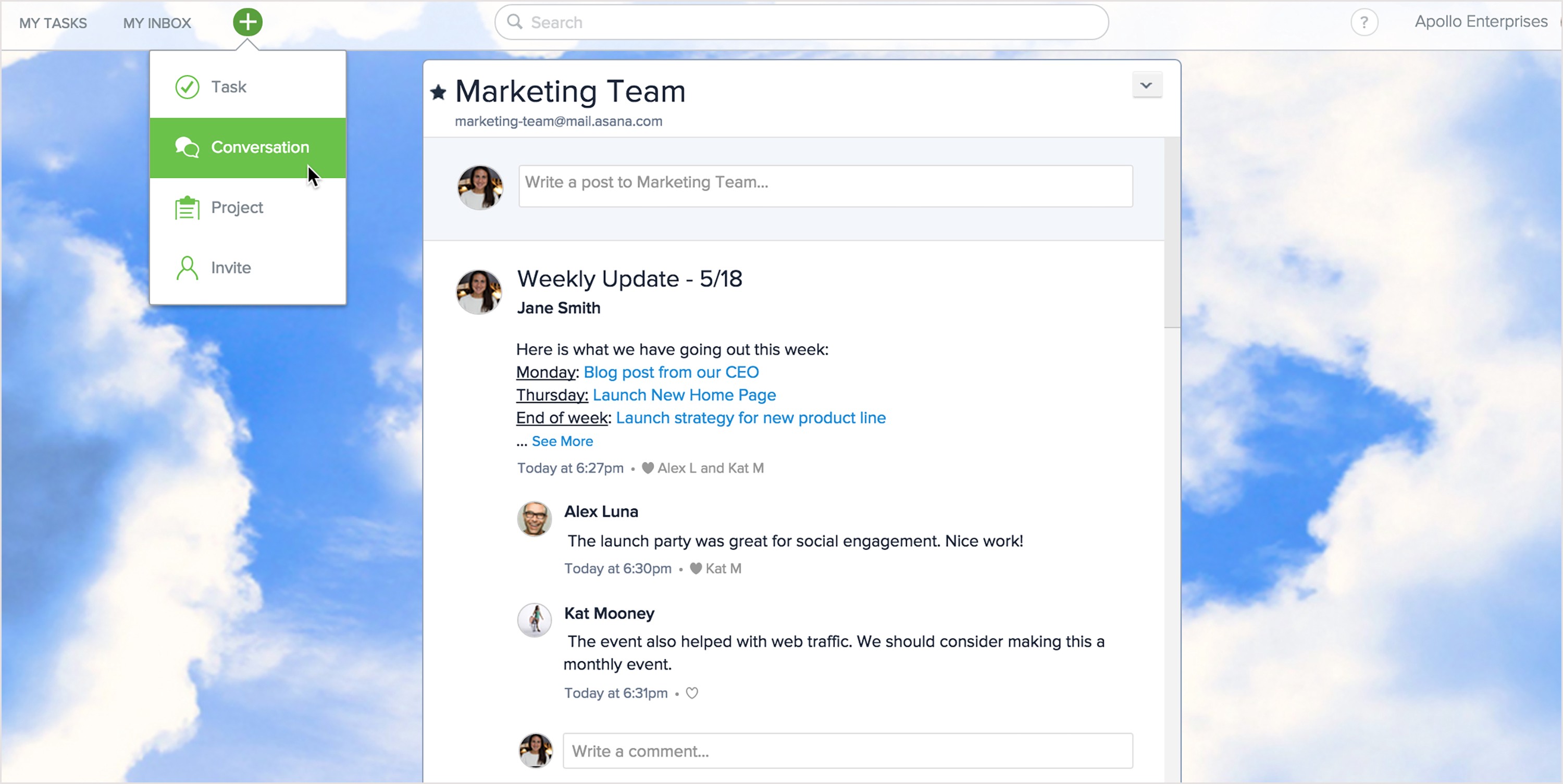

- GitHub and Asana (and DevResults) have discussions.

- Slack, Asana, FreshSales, and FreshDesk (and DevResults) have document storage.

Asana’s “Conversations” is a classic me-too feature: In principle it kind of makes sense to have discussions alongside your task lists. In practice, it doesn’t make sense to have lots of different venues for conversation, so we use Slack instead.

Their only advantage is that they’re linked to the app’s data model. They often weren’t part of the original product idea, but it’s very appealing to have that set of documents or that to-do list right next to the project or help ticket or whatever it is that it pertains to. That’s why customers asked for them, and that’s why they got built. But they’re almost always built in a half-hearted way, and there are always single-purpose tools that are better at these things.

4. Infrastructure

These are the things that every app has to have: User management, provisioning, authentication, permissions, an API and API documentation, subscription management and billing, search.

Again, some products nail the fundamentals better than others, but these are all problems that have been solved many times.

N apps = N user lists to maintain.

If you use ten SaaS apps, you have ten different lists of users to maintain; ten APIs to learn about; ten places to update your credit card information when the expiration date changes; ten different search UIs.

And you’re paying indirectly, ten times, for the cost of building and maintaining all this parallel infrastructure.

5. Customizability and integration

As we’ve already seen, if we get these at all, they’re implemented in a half-hearted and limiting way.

The holy grail

This framework gives us a way of thinking about what we’re getting from various apps in our toolset, and what an ideal arrangement would look like.

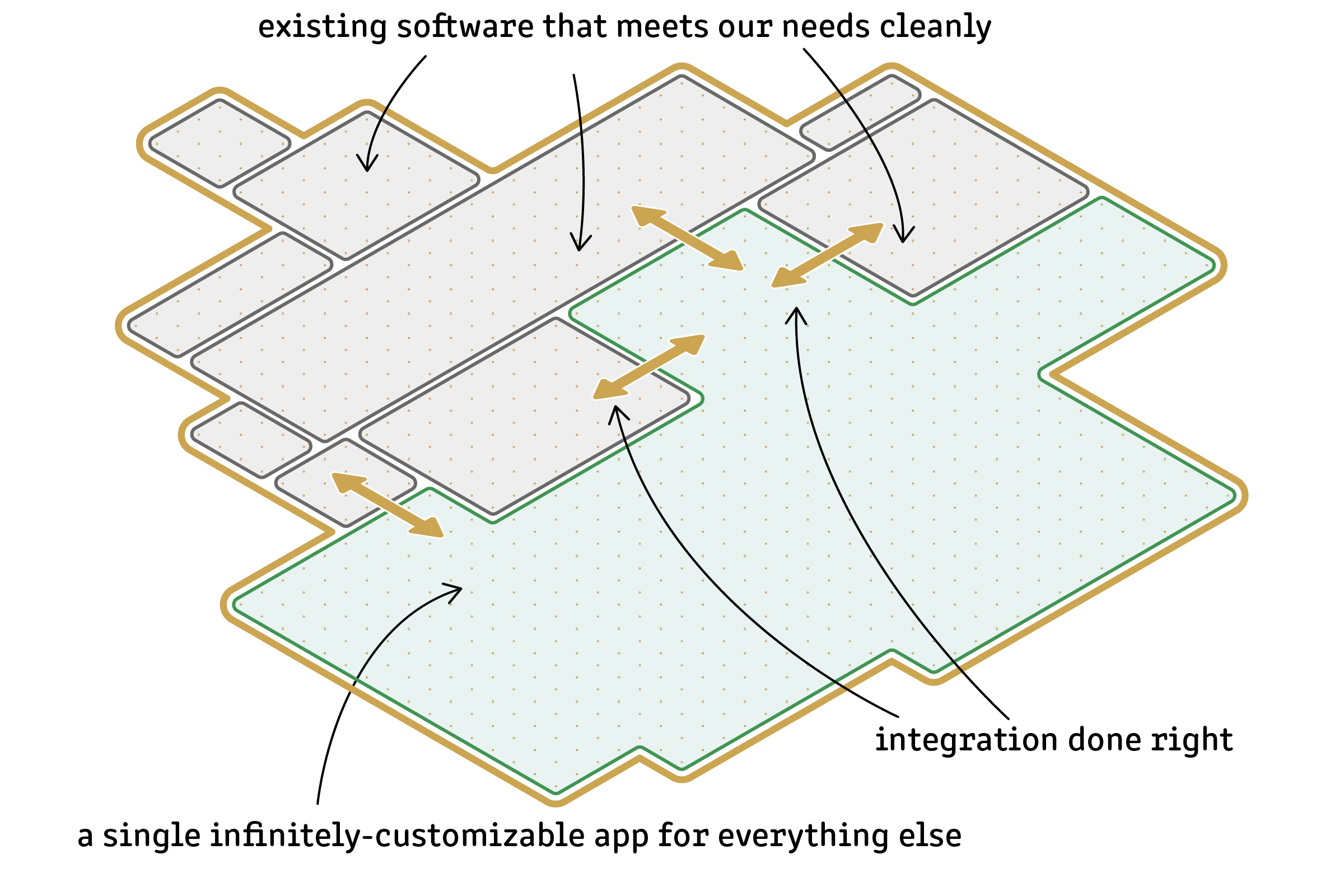

This is what I want. This turns the above model on its head:

- Customization and integration come first.

- Domain-specific data models are free, pluggable, and customizable.

- Common features are shared and linked, so there’s no need for duplicative me-too features.

- Superpowers are left to integrated apps — or better yet to infrastructure-free plugins.

I’ve thought a lot about what this application might look like. I’ll go into the details in a follow-up post.

I’ve also spent some time scouring the landscape for an existing app that fits the bill. (Spoiler: I haven’t found one.) In another post, I’ll take a look at some products in existing software categories that come close.