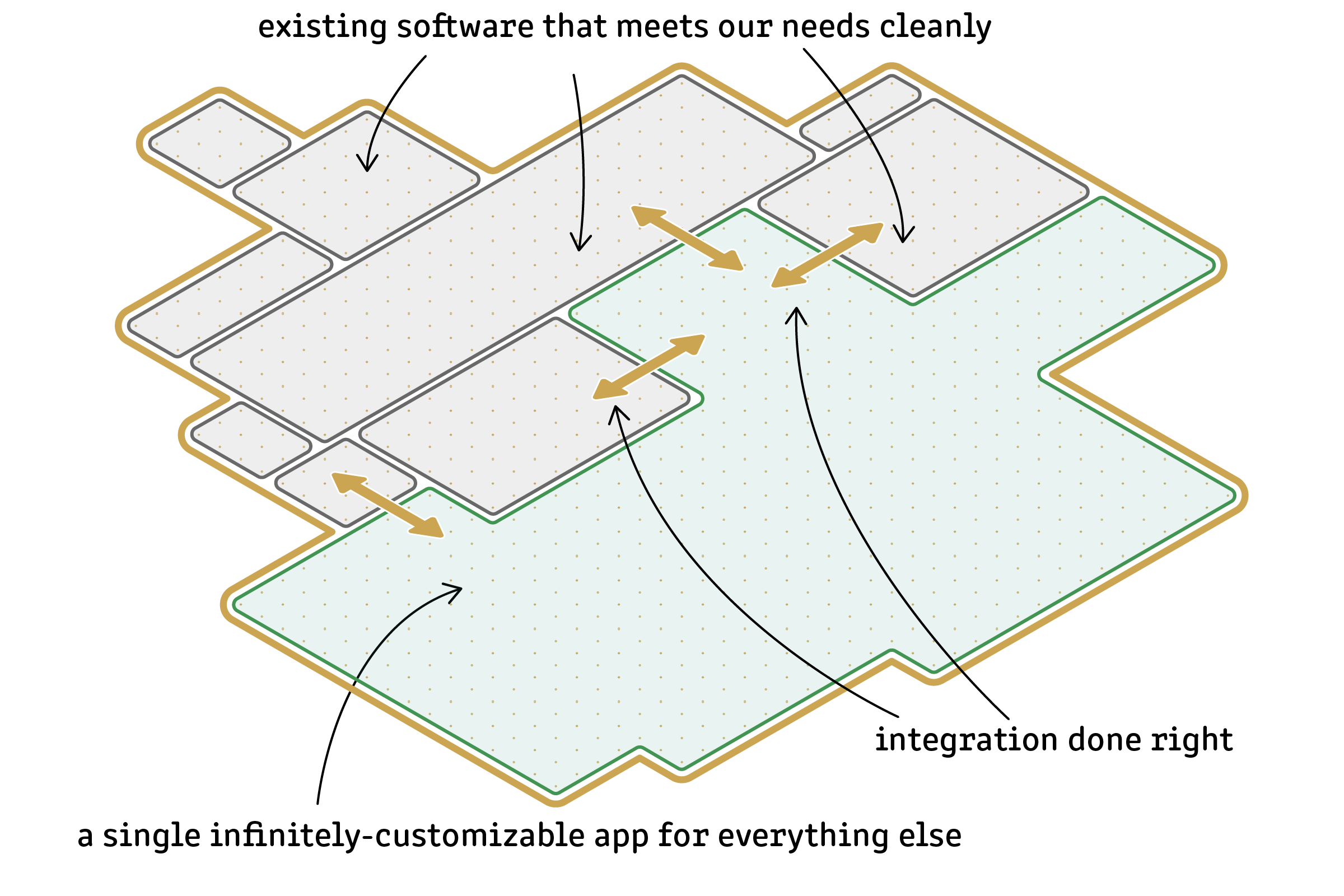

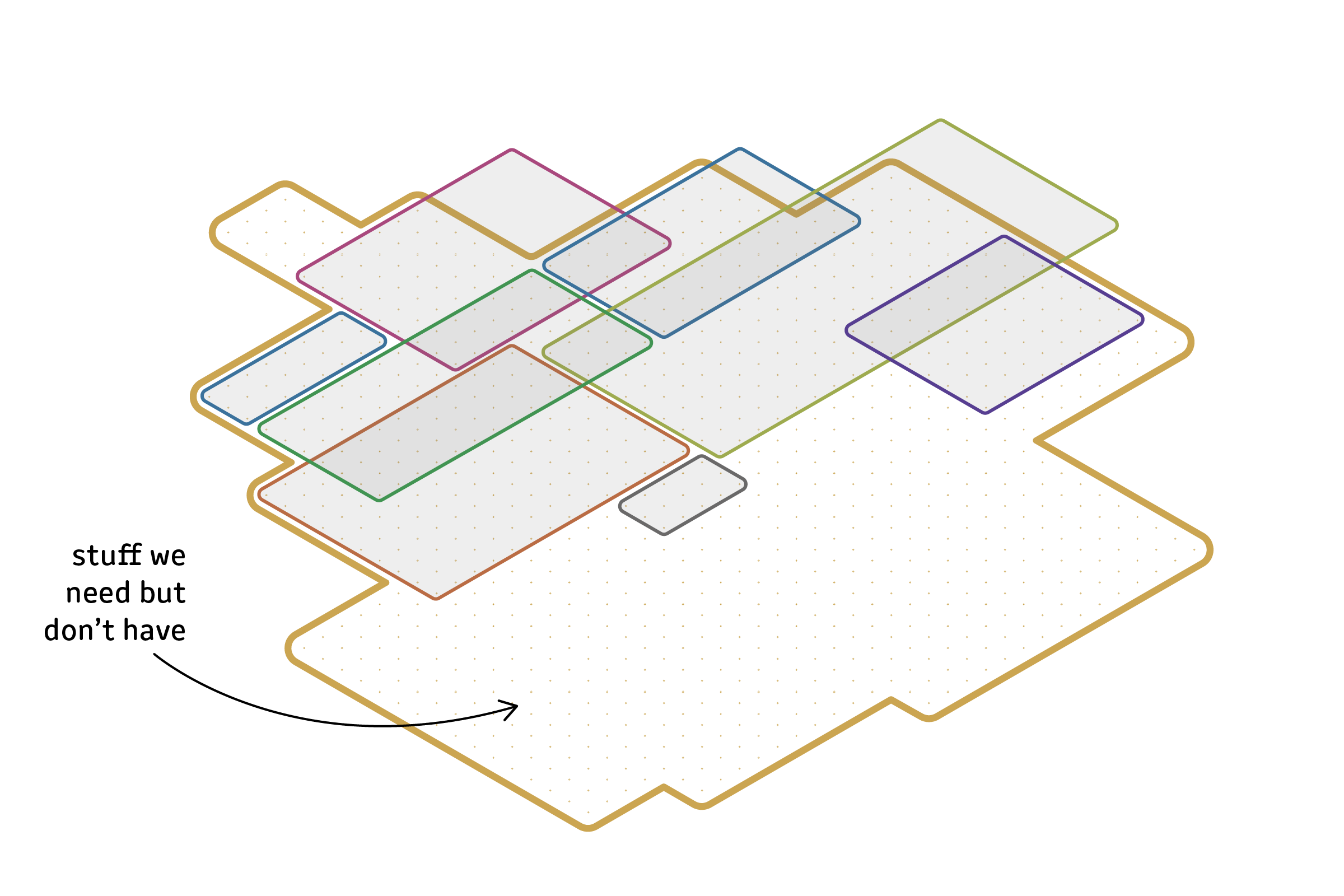

After writing many words about the challenges of building a SaaS toolset for a team, I concluded that the holy grail would look like this:

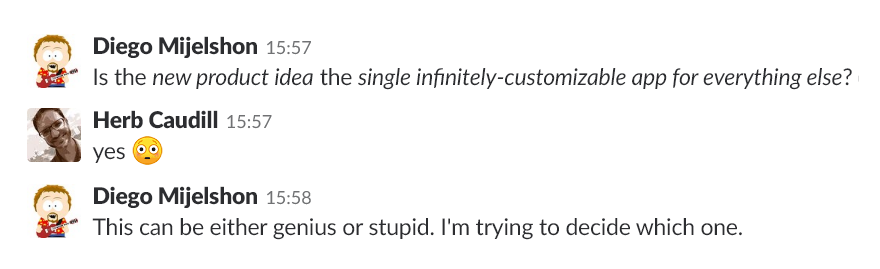

I’d mentioned to some people on my team that I was thinking over a new product idea. When I published that post, this was the first reaction:

The conventional wisdom in the software business is to do one thing well. In general that’s good advice, and that thinking has brought us some terrific, tightly-focused tools.

So it seems a little crazy to talk about building a multipurpose SaaS product in this day and age.

On the other hand, there’s clearly enormous demand for an extremely malleable general-purpose application. Exhibit A for that demand is Microsoft Excel.

The curious case of Microsoft Excel

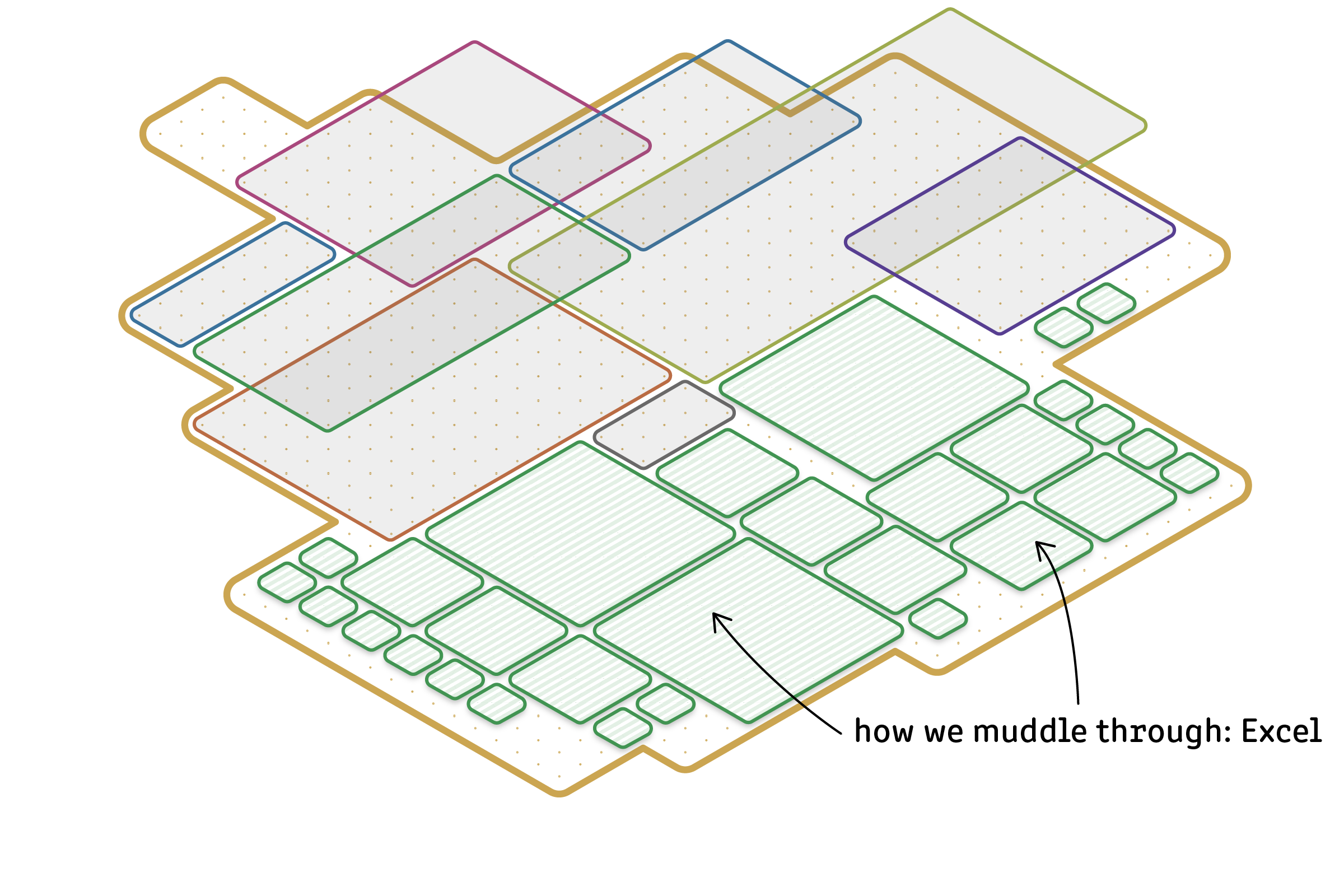

The reality of most teams, including mine, is this: We use purpose-built software for some stuff, and for the rest we use Excel.

In most cases, Excel is not up to the demands we put on it — but that doesn’t stop us. There are other tools out there that might be more appropriate, but we don’t use them.

Excel sucks and people love Excel. I think this is important. If we want to create something to replace Excel in that “stuff we need” white space, then we need to understand why Excel is so appealing in spite of its limitations.

Let’s take a little detour to think about this.

Excel is the world’s most widely-used “database”

It goes without saying that Microsoft Excel is the world’s most-used spreadsheet software. What is surprising, and of interest to us, is that Microsoft Excel is the world’s most used database software as well.

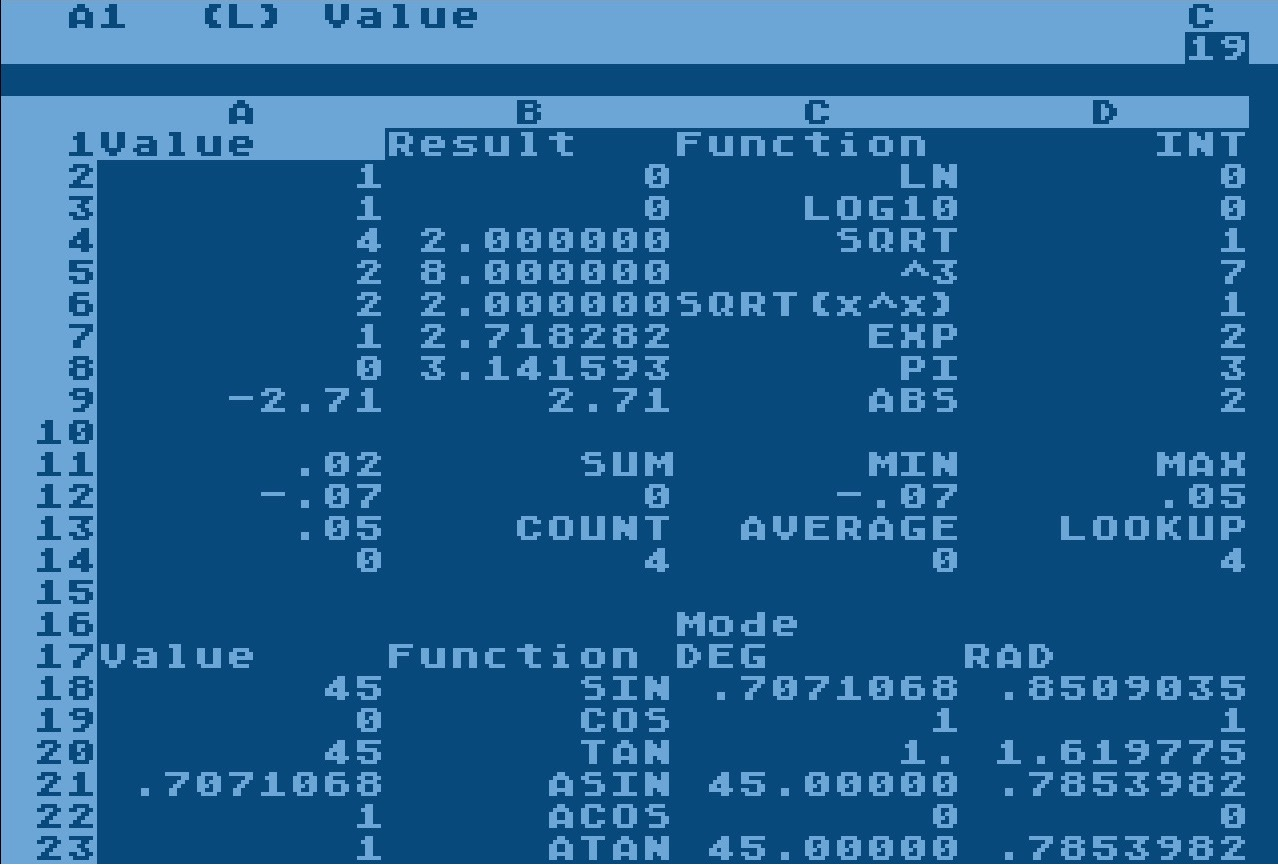

VisiCalc was the original killer app — software compelling enough to fuel sales of the hardware it ran on.

This isn’t what spreadsheets were made to do. This software category was introduced on the Apple II by VisiCalc — short for “Visible Calculator” — to do financial modeling. Bob Frankston, one of its creators, described it as “a magic sheet of paper that can perform calculations and recalculations”.

VisiCalc was supplanted by SuperCalc, then Lotus 1–2–3, and then Microsoft Excel. Each new generation advertised faster calculations, more functions, new “what-if” features. But in the early 1990s, Microsoft came to understand that most people didn’t use Excel for numerical computation: They used it for storage.

Joel Spolsky, who worked on the Excel team at the time, describes the moment when the team realized this:

Everybody thought of Excel as a financial modeling application. It was used for creating calculation models with formulas and stuff. … Roundabout 1993 a couple of us went on customer visits to see how people were using Excel. Over the next two weeks we visited dozens of Excel customers, and did not see anyone using Excel to actually perform what you would call “calculations.” Almost all of them were using Excel because it was a convenient way to create a table. Spreadsheets are not just tools for doing “what-if” analysis. They provide a specific data structure: a table. Most Excel users never enter a formula. They use Excel when they need a table. The gridlines are the most important feature of Excel, not recalc.

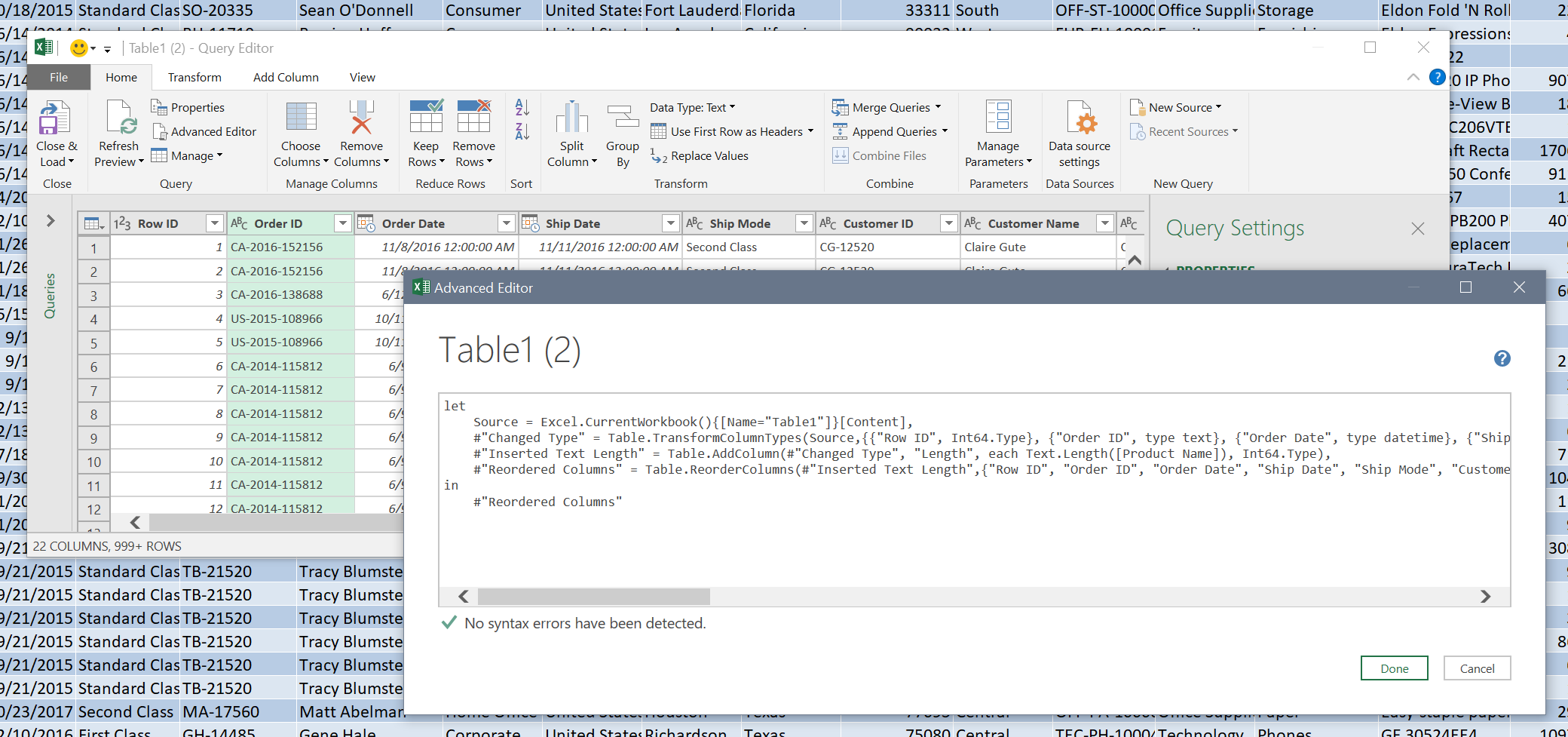

Realizing this, Microsoft belatedly started to add data-management features to Excel. The biggest single improvement was a feature tried in 2003 called, aptly, “Tables”. I suspect that 95% of Excel users don’t know it’s there. Microsoft is still retrofitting Excel with database functionality. Deep in the bowels of the “Data” tab you’ll find hardcore data manipulation tools that approximately no one has ever used.

Did you know you could create queries within an Excel spreadsheet to filter, project, transform, pivot or unpivot data from an existing table?

In spite of all that effort and all of the data-centric features that have been piled onto the product, it’s still an exercise in frustration to use Excel to manage data. Why is that?

Trapped in flatland

Excel’s most obvious limitation has to do with its very nature. There’s no getting around the metaphor of sheets of paper: a two-dimensional grid of rows and columns.

I believe there’s a moment in every Excel user’s learning curve when they realize that their information doesn’t fit in two dimensions, and their brain melts.

My wife, Lynne, is the prototype of the intelligent non-programmer. (She is also stunningly beautiful and very likely to read this.) I mentioned this idea to her, and she immediately knew what I meant. She told me about trying to use Excel to keep track of a training program across multiple hospitals: Venues, classes, syllabi, instructors, topics, participants. She got to a certain point, stared at the screen for a while, and said “Fuck it, I’m printing stuff out and buying a binder.” Paper 1, Excel 0.

Search Quora or StackOverflow and you’ll find dozens of variations of the question “Is it possible to store multiple values in an Excel cell?” or “Can I insert a table into an Excel cell?”

Listen closely, and you can hear the sound of someone’s brain about to melt.

If you have a certain type of background, you look at a situation like this and you immediately see one-to-many or many-to-many relationships, and you know the solution involves multiple tables, which you can link together with vlookup or index/match.

But most people’s brains don’t go naturally to a relational-tables model, and most people have never used those functions.

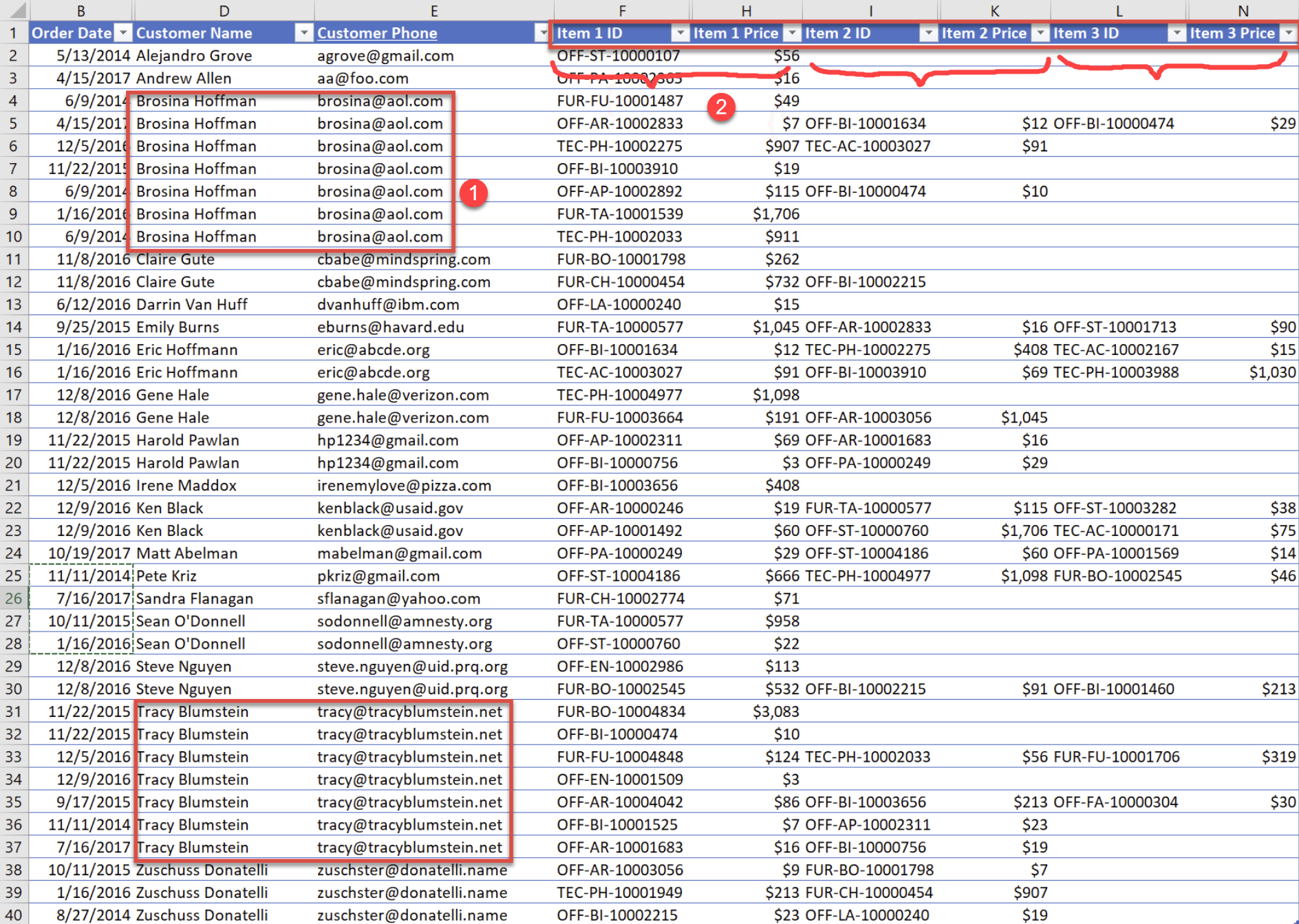

Two signs that you’ve outgrown Excel: (1) Repeating the same data over, and (2) a series of numbered columns.

So in the best-case scenario, you get around Excel’s two-dimensionality with multiple tables and vlookup hacks. More likely, you limp along with error-prone, labor-intensive horror shows like the one shown above — with information duplicated all over the place, and maybe with repetitive sets of numbered columns to spice things up.

No separation between data and presentation

Even if you’ve organized your data into strictly normalized relational tables, you’re very limited in terms of your ability to view the data.

That’s because in Excel, data and presentation are hopelessly commingled. This leads to irreconcilable tensions between two worthy goals — keeping the data clean on the one hand, and presenting it in a way that is readable and clear on the other.

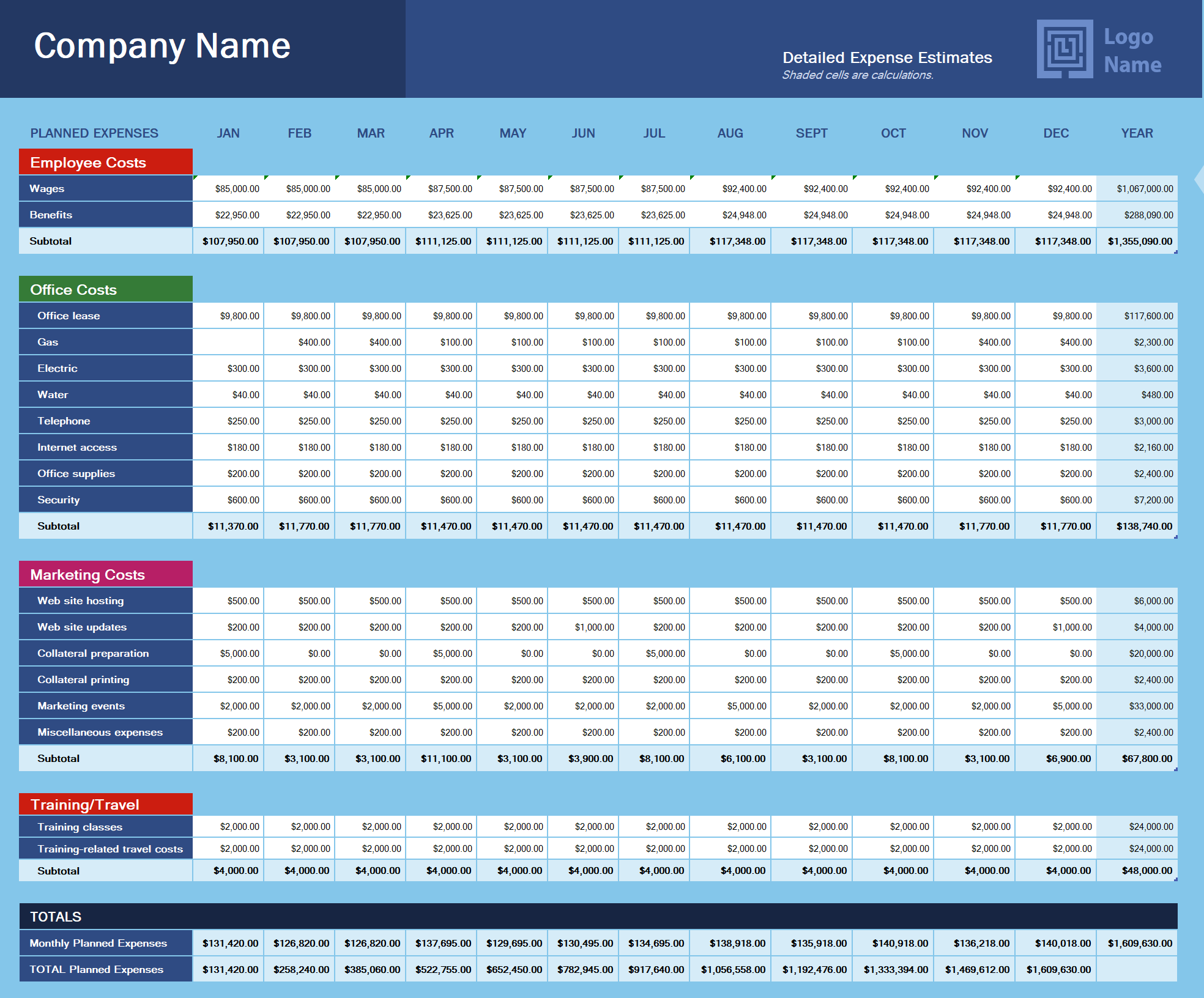

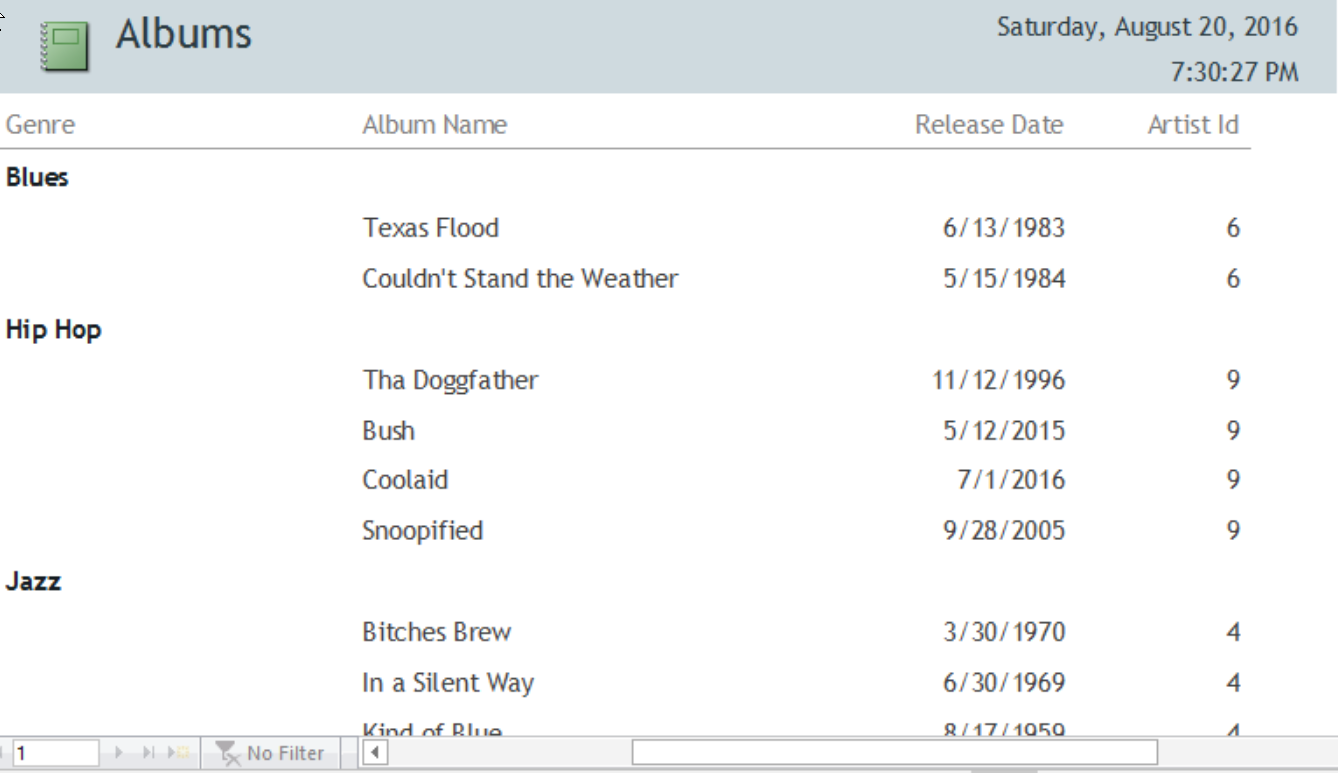

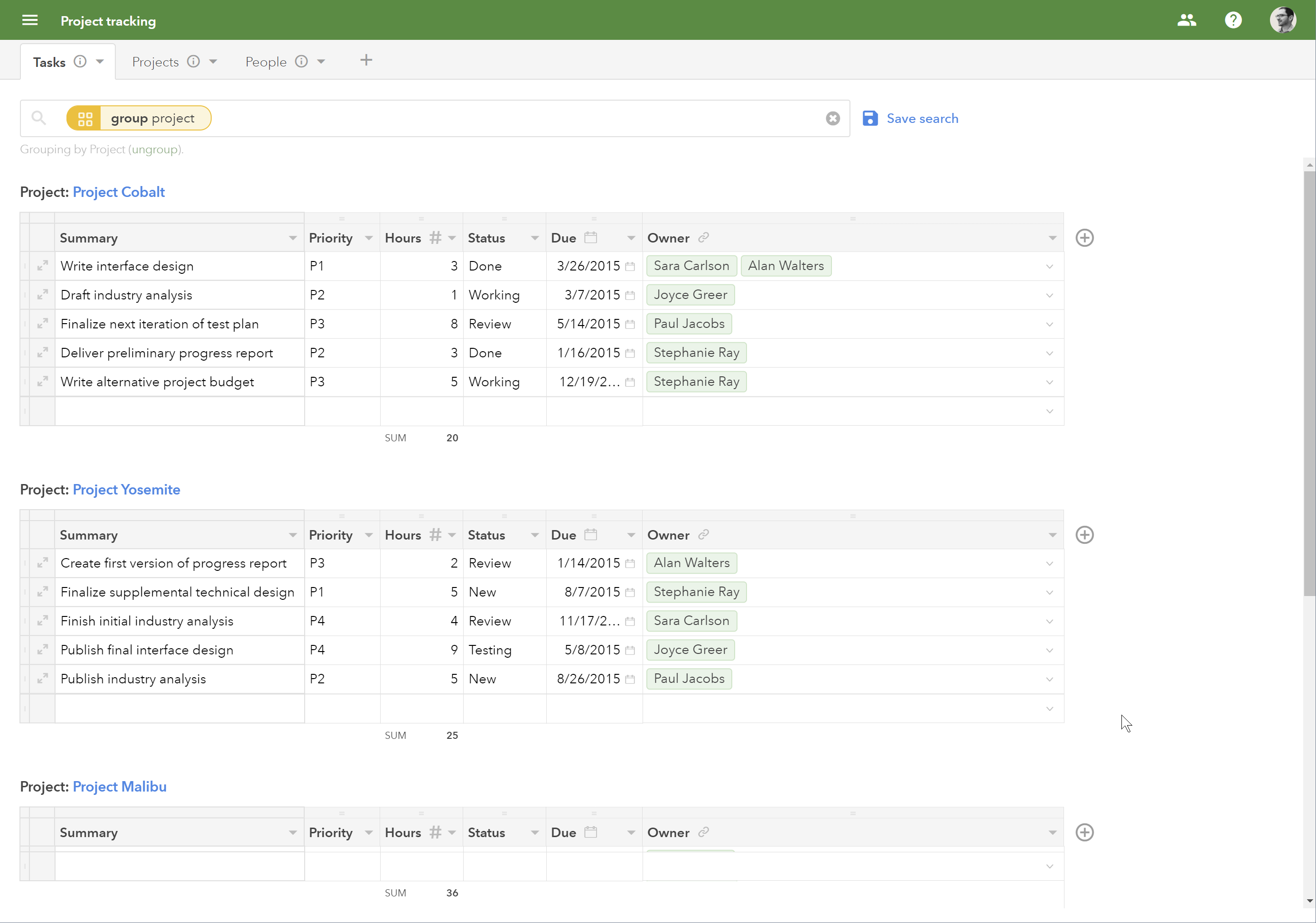

So people are naturally tempted to do things like this — manually grouping and subtotaling different categories, with blank rows and brightly colored labels:

This is an official template provided by the Microsoft Corporation. It’s pretty, but of all people, they should know better than to offer this up as a good practice!

If you know spreadsheets, you know that this spreadsheet would be a nightmare to work with. You can’t get numbers into it or out of it without repetitive copying or pasting, or retyping. And it’s brittle — look at it wrong and you’ll break something. Just picture in your head what’s involved if you want to add a new expense category, or remove an existing one.

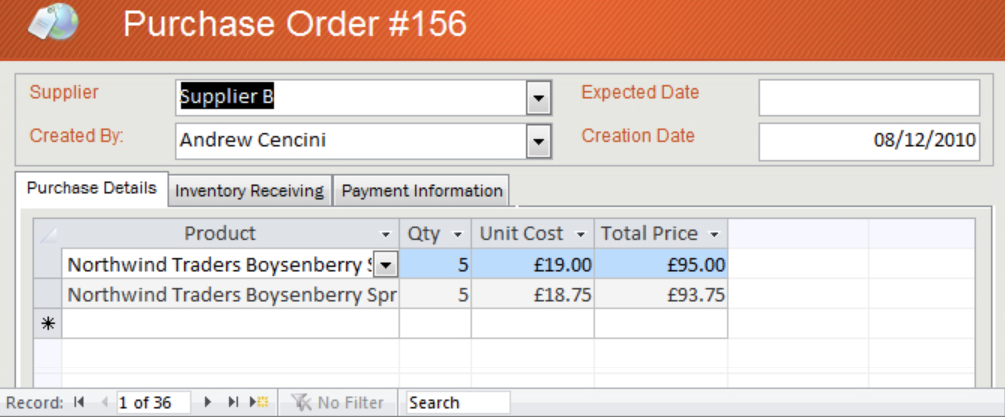

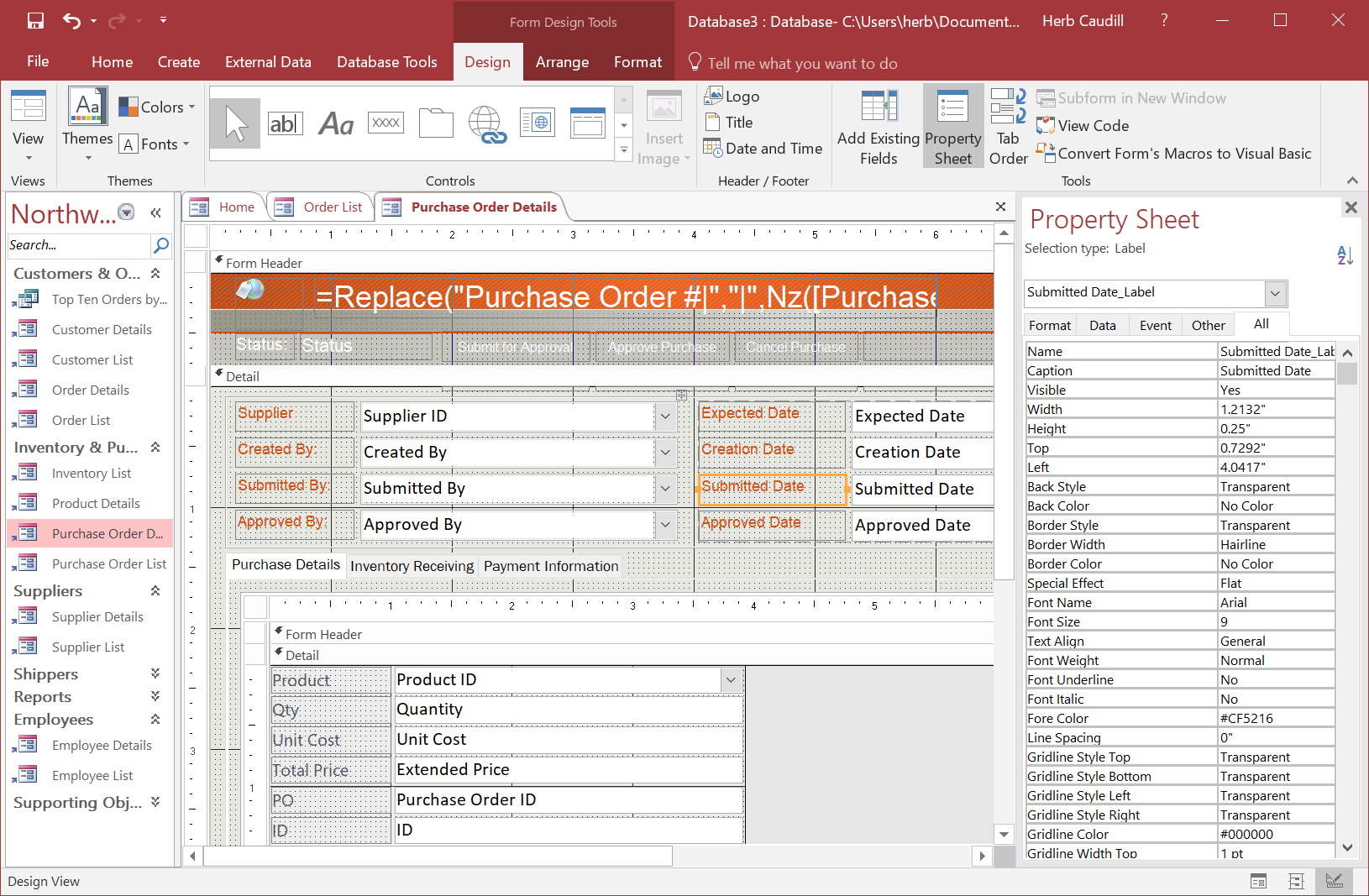

Even if you’ve done everything right, you can’t create these kinds of views on your data in Excel.

There’s no way to create a natural view of data with one-to-many or many-to-many relationships — for example a form or report like these, that draws from tables of data that are stored elsewhere.

Error-prone

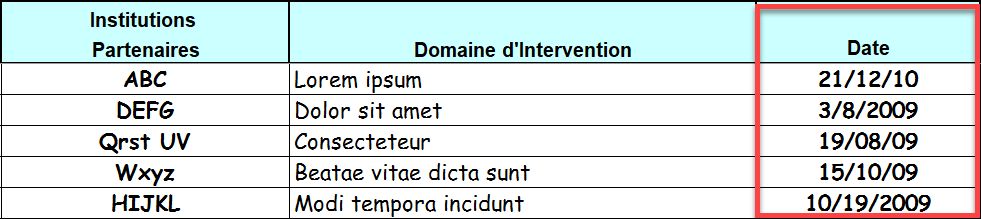

The downside of Excel’s flexibility is that it’s really, really easy to do the wrong thing. You can enter text into a numeric column. You can type something that looks like a date but isn’t.

Some of these were entered as M/D/Y and some as D/M/Y. Can you tell which is which?

You can inadvertently delete rows, type over a formula, omit cells from a calculation, or worse. Mistakes in Excel formulas are easy to make, hard to notice, and hard to debug.

As a result, the internet is littered with Excel horror stories, from the $25-million budget shortfall to the $6-billion trading loss to the incorrect policy advice that deepened a recession.

File-based

Twelve years after Google Sheets was introduced, and ten years after Microsoft launched Excel Online, most spreadsheet “systems” are still files that live on a server or on someone’s hard drive somewhere.

As a result:

- Only one person can use them at a time.

- They get emailed around, which is insecure.

- You end up with multiple versions with cryptic names like “Budget v3 (FINAL) modified HC Feb2018 (clean).xlsx”.

So why don’t people use database software instead?

So: We’re agreed that Excel isn’t a great tool for managing a database. If you Google “Why do people use Excel as a database” you’ll turn up page after page of rants, making the not-unreasonable two-part argument that:

- Excel is not database software; and

- If you need a database you should use database software.

So let’s talk about Microsoft Access, which is database software, and which doesn’t have these limitations.

- Access is designed around a SQL-like structure of relational tables with normalized data.

- Its columns are typed, so you can’t enter a non-date in a date column or text in a numeric column.

- Presentation and data are cleanly separated, so you can create various views, forms, and reports on top of the underlying data.

So why don’t more people use Access? It’s not because they’re too dumb to figure it out. My team includes four data scientists and five programmers. We can all write SQL in our sleep. We use spreadsheets a lot and we don’t use Access at all.

The reason, I think, is best summarized in Venkatesh Rao’s answer on Quora to the question “Why do many people still use Excel as a pseudo database?”:

One is a workspace for humans, the other is a store for programmatic manipulation.

Excel greets you with an empty, non-judgmental grid: You can start typing and very quickly get some degree of clarity and organization. Datasets in a spreadsheet are malleable, allowing you to be experimental and incremental.

Access, on the other hand, forces you to do a certain amount of upfront thinking about the structure of your data. Once you’ve defined that structure and started filling it up with data, it gets harder and harder to make changes to it.

Excel is no good for data. Access is no good for humans.

This tension between spreadsheets and databases gives us a starting point for what A Single Infinitely-Customizable Tool For Everything Else might look like.

It has to let me easily create lists and tables like Excel. But in the long run it has to give my data a more solid structure like Access does.

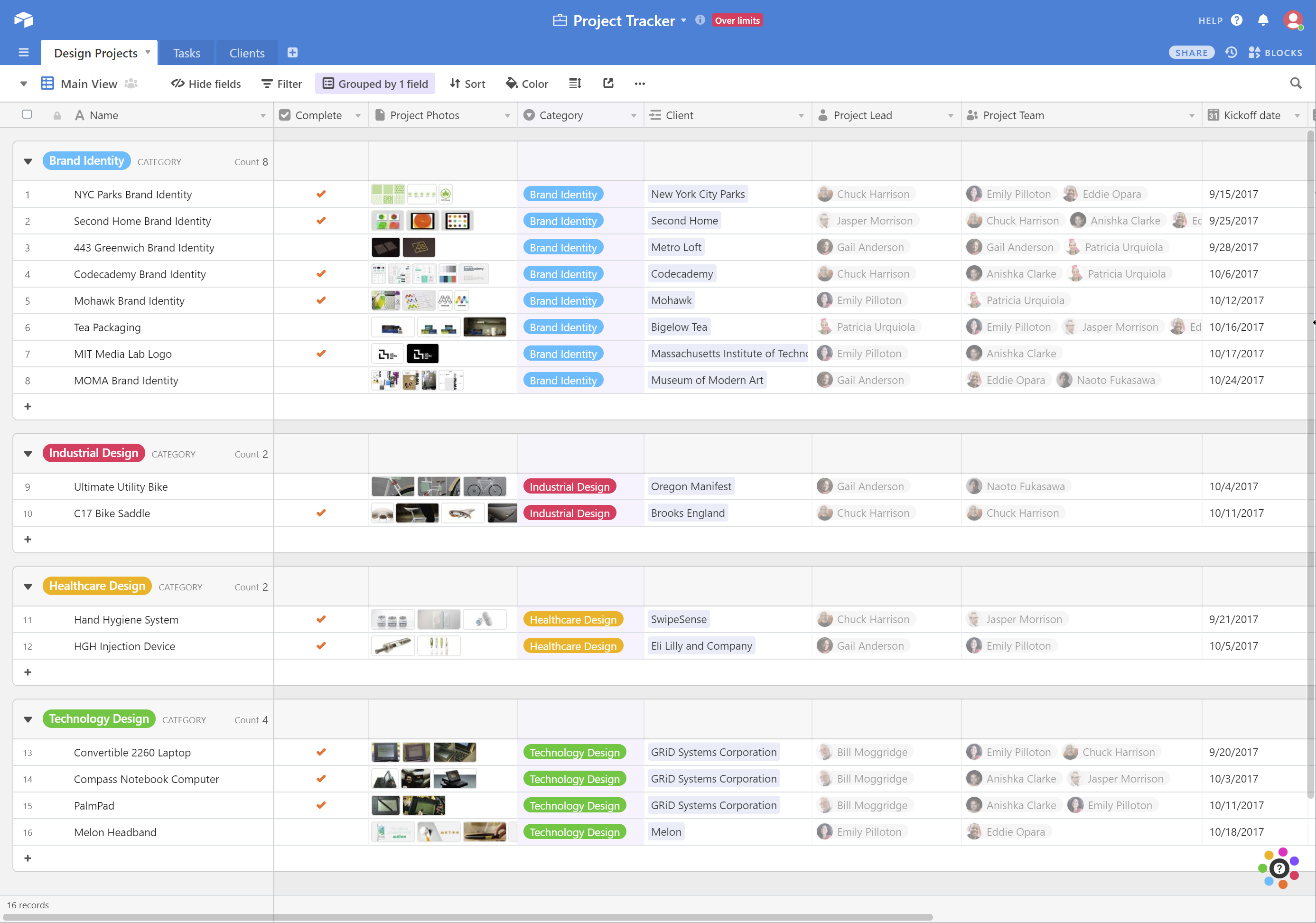

Fieldbook (left) and Airtable both advertise the simplicity of spreadsheets combined with the power of a database.

As a product idea, “Spreadsheet meets Database” is not new. Airtable (“Looks like a spreadsheet, acts like a database”) and Fieldbook (“As simple as a spreadsheet, as powerful as a database”) beat me to it. They’re good products, and a step in the right direction. And there are dozens more products in this vein.

But I think we can go a step farther than just mashing up two existing product categories.

There are a couple of problems that the current crop of SpreadDataSheetBase products inherit from the database side of the family.

One problem with databases is that they force me to start naming and defining things before I have data.

I want to just start typing in stuff without defining my data model in advance, and then start naming and defining things as a schema emerges from the data.

When that critical moment arrives and I realize that my data doesn’t fit in a grid, my brain shouldn’t melt; in fact it should be natural and obvious how to capture that complexity.

Which brings me to the larger issue with today’s user-facing database products, which is that they force me to cram my reality into linked two-dimensional tables.

The relational data model is wonderful; but it was invented to make things easy for machines, not for humans. And if you spend any time talking to intelligent civilians about their struggles using Excel as a database, you’ll realize that it’s not a model that occurs naturally to many people.

Thinking outside the grid

I have a theory that a loosely-typed object-oriented model, like JavaScript objects or JSON documents in a NoSQL database, is a more natural fit for most people’s mental models than a strictly-typed relational table structure.

Photo © 2011 by Simon Bramwell

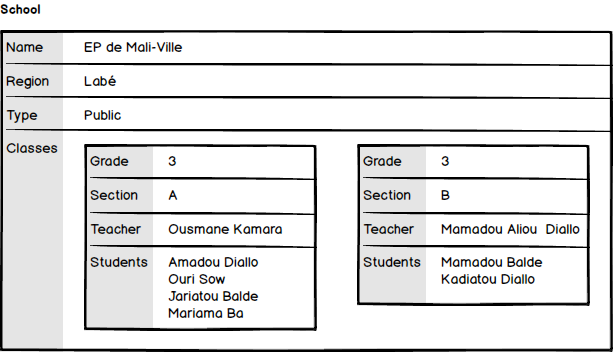

I was recently talking with a DevResults customer who was managing data from an educational project that works in several developing countries. Since this scenario is fresh on my mind, let’s consider a simple data model for a school.

In this model, a school “has” a name, a region, a type, and a list of classes. It’s not unreasonable to think of each of these things as a field or a property of a school, even though one of them is a list.

Likewise, a class “has” a grade, a section, a teacher, and a list of students.

We can capture this information in a JavaScript object or a JSON file in a succinct way that aligns nicely with our mental model.

{

name: 'EP de Mali-Ville',

region: 'Labé',

type: 'Public',

classes: [

{

grade: 3,

section: 'A',

teacher: { first: 'Ousmane', last: 'Kamara' },

students: [

{ first: 'Amadou', last: 'Diallo' },

{ first: 'Ouri', last: 'Sow' },

{ first: 'Jariatou', last: 'Balde' },

{ first: 'Mariama', last: 'Ba' },

],

},

{

grade: 3,

section: 'B',

teacher: { first: 'Mamadou Aliou', last: 'Diallo' },

students: [

{ first: 'Mamadou', last: 'Balde' },

{ first: 'Kadiatou', last: 'Diallo' },

],

},

],

}

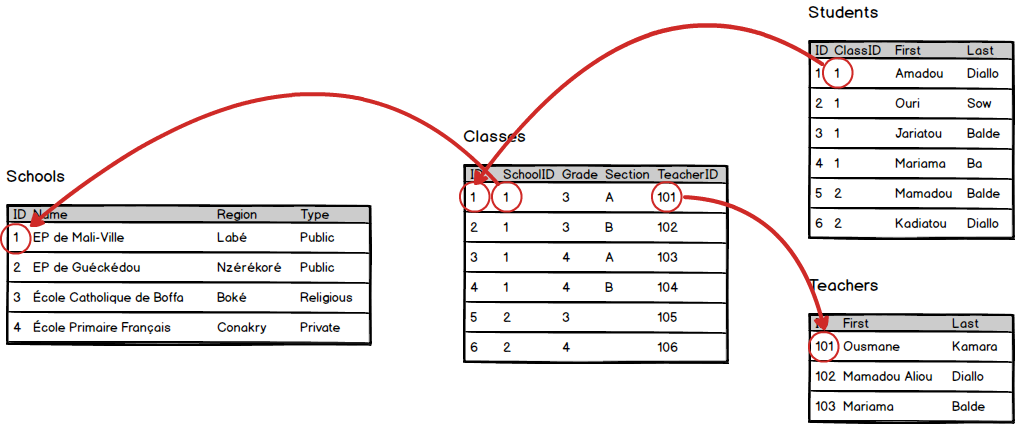

In contrast, the relational model of the same data introduces a weird layer of abstraction and indirection.

This is weird for a couple of reasons.

Even though a class has no free-standing existence outside of a school, we create a table that only contains classes. It’s weird that if you look at a school, you’ll find no mention of its classes; and if you look at a class, you’ll find no mention of its students. Rather, the class is stored as a property of a student, and the school is stored as a property of a class.

Now, this abstraction makes total sense once you understand it. But it’s unnatural. It maps awkwardly to my internal representation of reality. (In related news, relational data also maps awkwardly to the object-oriented code it has to be translated to.) This awkwardness creates a set of cognitive obstacles that most people don’t make it past.

If my “easy-to-use database” requires me to conceive and implement this non-intuitive structure before I can enter the information for a single school, I may very well conclude that I’m better off with paper and a binder.

One cognitive obstacle is the tabular model, which locks us into rows and columns, with each cell containing a primitive value: a number, or a date, or a string of text.

An object model frees us up to think about things in a recursive, hierarchical way. As it turns out, this is how the human brain is wired to represent reality. Things are composed of other things, which are in turn composed of other things. A property of a JavaScript object can contain a primitive value, but it can also contain a complex object with its own properties. Or it can contain an array, which in turn can consist of simple values or complex objects.

Now, this is not to say that tables are passé as a way of viewing and organizing information. There’s a reason why Excel’s gridlines are so compelling. A table is a clear and concise way of displaying a set of facts (columns) about a collection of similar objects (rows). But it’s not the only way! There are lots of other ways to visualize a collection — an outline, a network graph, a timeline, a map, a kanban board. Most database UIs I’ve seen begin and end with tables, and I suspect that’s in large part the underlying tabular storage technology showing through.

Another cognitive obstacle is the strong typing requirement: In a relational database, you can’t enter data before you’ve decided what type of data each field of each table will contain. That’s as true of SQL Server as it is of Airtable.

In loosely-typed environments like JavaScript and NoSQL databases, I can create a schema but I don’t have to. That gives me the flexibility to just enter my stuff without thinking about it too much at first — like in Excel — and allow the schema to emerge later.

Because it is helpful to have a schema at some point: If the software knows that a field should only contain dates, it can reject non-date input; it can offer me a helpful UI like a date-picker; and it can offer date-based views like a calendar, a timeline, or a timeseries chart.

But the schema should know its place. Its job is to serve, not to run the show. It shouldn’t insist on coming first. I should be able to modify it as needed. It should observe quietly, inferring types where possible from the data (much the way Excel recognizes dates and currency amounts when they’re typed in, and applies the corresponding formatting) and only asking for clarification when something I want to do requires it.

To be clear, the notion of relations isn’t a cognitive obstacle. In the JSON snippet above, I’ve embedded the teachers’ information directly in the class. In this scenario, perhaps it’s a good idea to store a list of teachers separately, and just store references to them; that way if we misspell a teacher’s name we only have to fix it in one place. I’m guessing that our intelligent civilian can probably handle that just fine, and transition easily from the model described above to something like this:

{

name: 'EP de Mali-Ville',

region: 'Labé',

type: 'Public',

classes: [

{

grade: 3,

section: 'A',

teacher: 101,

students: [1, 2, 3, 4],

},

{

grade: 3,

section: 'B',

teacher: 102,

students: [5, 6],

},

],

}

The difference is that a relational database forces you to put everything in a remote table, even where it doesn’t make sense — so classes have to be stored separately from schools. In an object model, you have the choice.

What would be even better would be if the software treated that as an internal implementation detail, and spared me from having to think too much about whether an object is stored in embedded form or as a reference.

OK. So our product description is starting to take a little more shape:

- It gives me an easy entry point like Excel, and some relational power like Access.

- It doesn’t require me to give things a lot of definition up front, but it allows me to do so when necessary.

- Instead of exposing an underlying structure of tables and rows, it exposes an underlying structure of arrays and objects.

- I can see my information in tabular form, but I also have access to lots of other visual representations that might make sense for my data.

- And of course, it’s all delivered in the browser, so it supports real time collaboration; and the app and the data live in the cloud, so it’s highly available and scalable and all that.

This is probably still a little hard to picture. I have many thoughts about what the user interface would look like, but I’ll stop now and share some sketches and mockups in a subsequent post.