A key difference between a table in a spreadsheet and a table in a database is that database columns are typed: If you’re storing dates in a column, all the values in that column have to be dates.

Consistent data types are a big part of what makes a database a database — and what makes a database more powerful than a spreadsheet.

But, as we’ve seen, data types are also a key point of friction for non-technical users, because they have to be nailed down too early in the process.

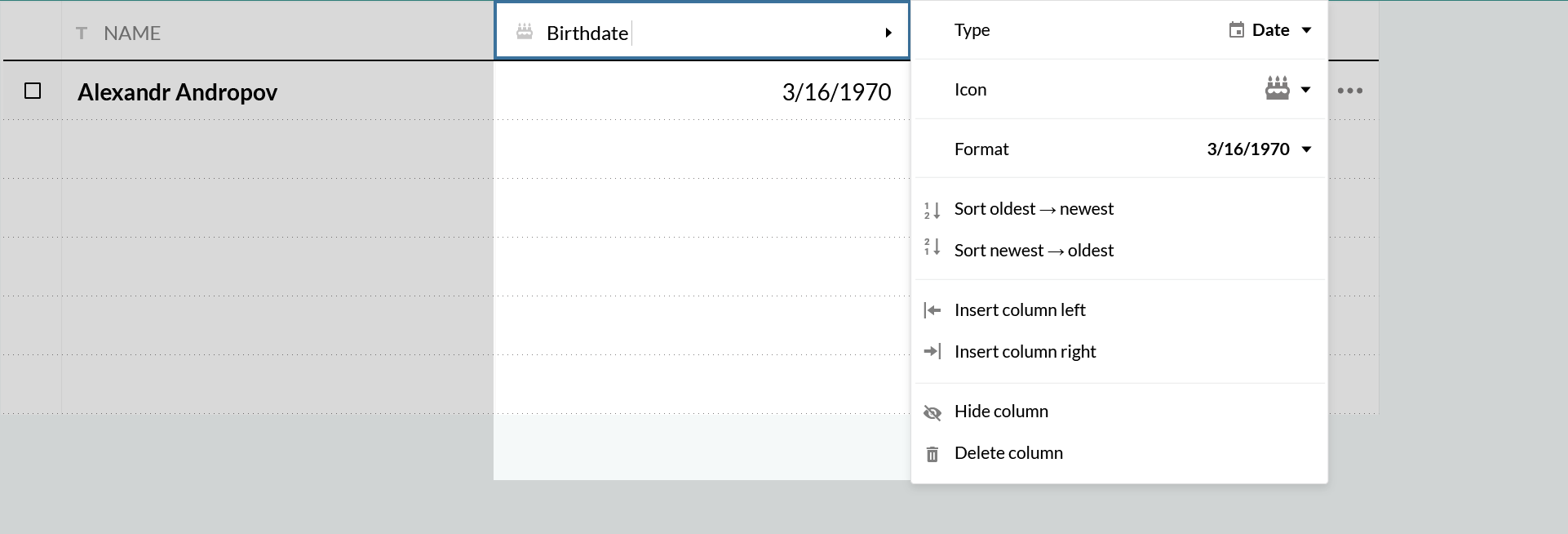

To get the best of both worlds, we want to avoid being heavy-handed: We don’t want to force Celeste to lay out her table schema in advance, but we do want to be smart and try to figure out her intentions. So if she types in a date, we’ll assume this is a date column. We’ll pick up the date format from the way she’s typed it in. And if she changes her mind and needs to change a column from one type to another, we want to make that as effortless as possible.

We want a column to pick up the date format from the way it’s typed in — just as it would in Excel.

Before we go any further with this, though, let’s talk about data types.

Towards humane data types

I propose that the friction here doesn’t necessarily all come from having to choose a type in advance. The problem is also that most database systems force you to think about types from the computer’s perspective.

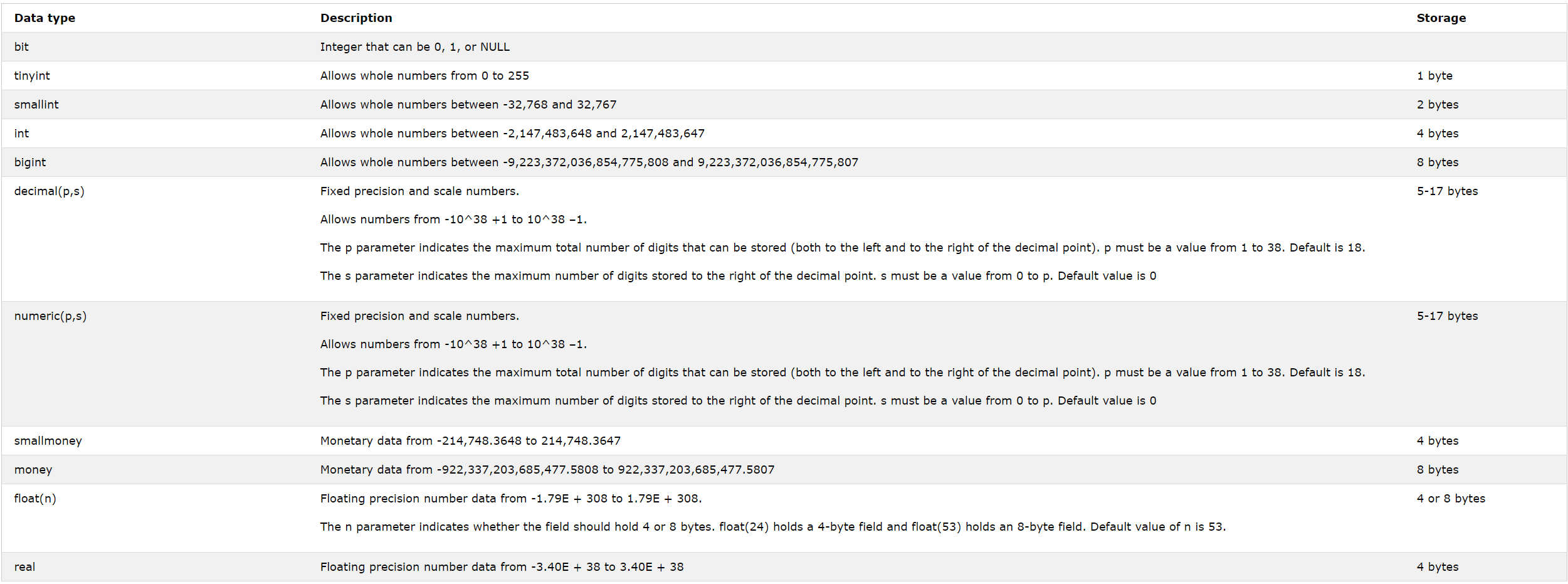

You only have a few fundamental types to choose from (text, number, date, boolean) and within those categories you have to make some commitments about how much space the computer should set aside. So for example, if you’re going the store numbers in a column, the system really wants you to make a lot of decisions in advance about size, precision, and so on.

SQL Server’s datatypes. Do you want int or bigint? Any programmer worth her salt can tell you a story about making the wrong choice and coming to regret it.

Human beings have different concerns. Does this number represent an amount in Euros or in Dollars? Or is it a measure of weight, or length, or area? What if it’s a distance in kilometers, but I want to show it in miles to some users? Does this text represent phone numbers or RGB colors?

With today’s databases, if you care about any of those things, you’re going to have to do the heavy lifting.

So basically you, the human, have to give a lot of thought to implementation details that should be the computer’s concern; but then when you want the computer to help you out with silly things like currencies or countries or weights or measures or oh, I don’t know, BASICALLY ANYTHING HUMANS CARE ABOUT, you’re on your own.

I think that’s the opposite of how it should be.

So what data types would actually be helpful to Celeste?

I think these categories ought to be front and center:

- Dates and times

- Physical measures: length, distance, weight, etc.

- Names, addresses, and other multi-part human artifacts

- Countries, states, currencies, languages, and other canonical lists

- References to other things in the same system

Let’s look at each of these in turn.

Dates and times

The passage of time is of fundamental concern to us humans, perhaps owing to the fact that we all die.

Most computer systems have something like a datetime datatype that allows you to identify an instant in time, down to the millisecond: for example, Wednesday, June 7, 2018, 9:45:23.1234 (Greenwich Mean Time).

And maybe that is, in fact, what we are interested in.

But it’s often either a date with no time or a time with no date:

June 7, 20189:45 AM

Or, it could be a related, but distinct, concept such as:

A duration:

30 milliseconds5 days42 years

A period of time:

- the year

2007 - the month of

May 1997 Quarter 1 of 2019

A standalone day of the year, month or day of the week:

- every

March 16 - every

February - on

Tuesdays

Today’s databases are of very little help with managing these constructs.

Now, there are libraries in most programming languages to help programmers represent these concepts cleanly. For example, the js-joda library for JavaScript (based on the joda-time package for Java) does a great job. But database tools supposedly designed for non-programmers — like Access or Airtable — mostly leave those users to struggle unassisted with the database’s raw data types.

This is going to be a recurring theme: There are so many great programming libraries and frameworks and concepts that have made things very clean and simple and straightforward for programmers. But no one has taken these ideas one small step further and wrapped them up in a form that makes them usable to civilians!

Physical measures: length, distance, weight, etc.

Another amusing human idiosyncrasy is that we have multiple incompatible systems to measure the physical world.

The good news is that the rules for converting, say, 5'8" to 172.72 cm are well-known and involve simple math. Computers are better at simple math than people are. A thoughtfully designed system would take advantage of that fact to transparently take care of those conversions — so that one user could enter data in feet and inches, while another users would see the same data expressed in centimeters.

Again, there’s no shortage of free libraries to help with these concerns: For example, the convert-units library for JavaScript can handle not only everyday things like length, distance, weight, and temperature — but also more specialized physical measures like acceleration, frequency, or volume flow rate. But again, unless you have the wherewithal to write your own software, these don’t do you much good.

Names, addresses, and other multi-part human artifacts

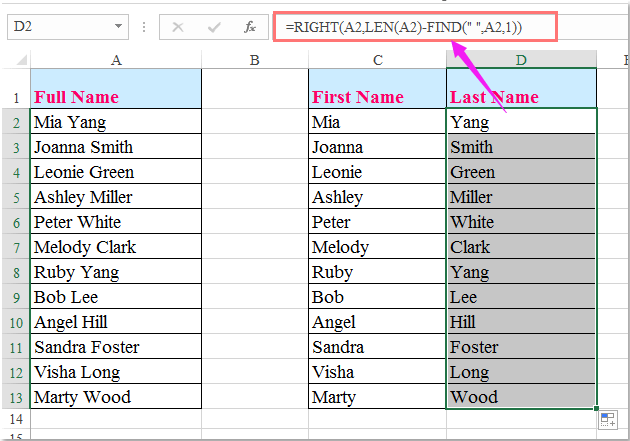

If you’ve ever created a table of contacts in Excel, the first thing you’ve had to deal with is human names.

Perhaps you started with a single “name” column. Then, you realized you wanted to sort by last names, so you figured out how to automatically split a full name into a first name and a last name:

But then start seeing names like these…

J. Shane KunkleHerbert “Herb” Caudill IIIJosep Puig i CadafalchDr. John P. Doe-Ray CLU, CFP, LUTCBrigadier General Zebulon Pike

…and you decide to call in sick and spend the day under the covers.

And then there are addresses. Do you need one or two address lines? Three? Do you support international addresses? Do you need to break out street numbers? Apartment numbers?

What would the “pretend it’s magic” solution for handling names and addresses look like?

What I’d like would be to just paste them in, as-is — but have the computer figure out their component parts. That way I’d still be able to sort people by last name, or pull out their initials or their preferred given names. And I’d be able to display addresses in a standard format, or group them by zip code or by country.

The good news is that we don’t need magic in this case, neither do we need to write a lot of code. Parsing and normalizing human names is hard, but it’s mostly a solved problem. Same for addresses .

The same approach applies to other fascinating human artifacts like phone numbers, RGB colors, and IP addresses. There are tons of existing services and open-source libraries to choose from for each of these. There’s no reason to force people to come up with their own home-grown solutions to these basic needs.

Countries, states, currencies, languages, and other canonical lists

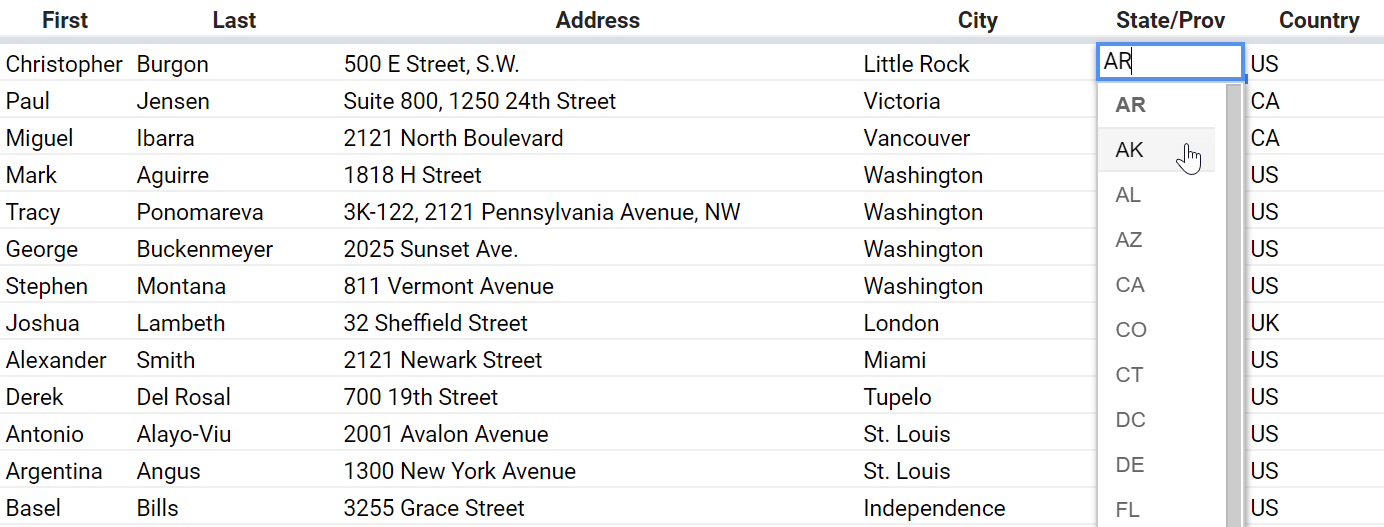

Another hassle you might have dealt with in your contact spreadsheet is the problem of inconsistently entered names — for U.S. states, countries, and so on.

If you’re given this data and you want to do anything at all with these columns, you have to go through and make them consistent by hand.

And if you want to make a spreadsheet that forces people to choose from as set of options so that it stays clean, you have some hoops to jump through.

If you know how to make this happen, you’re in the elite 1% of spreadsheet power users.

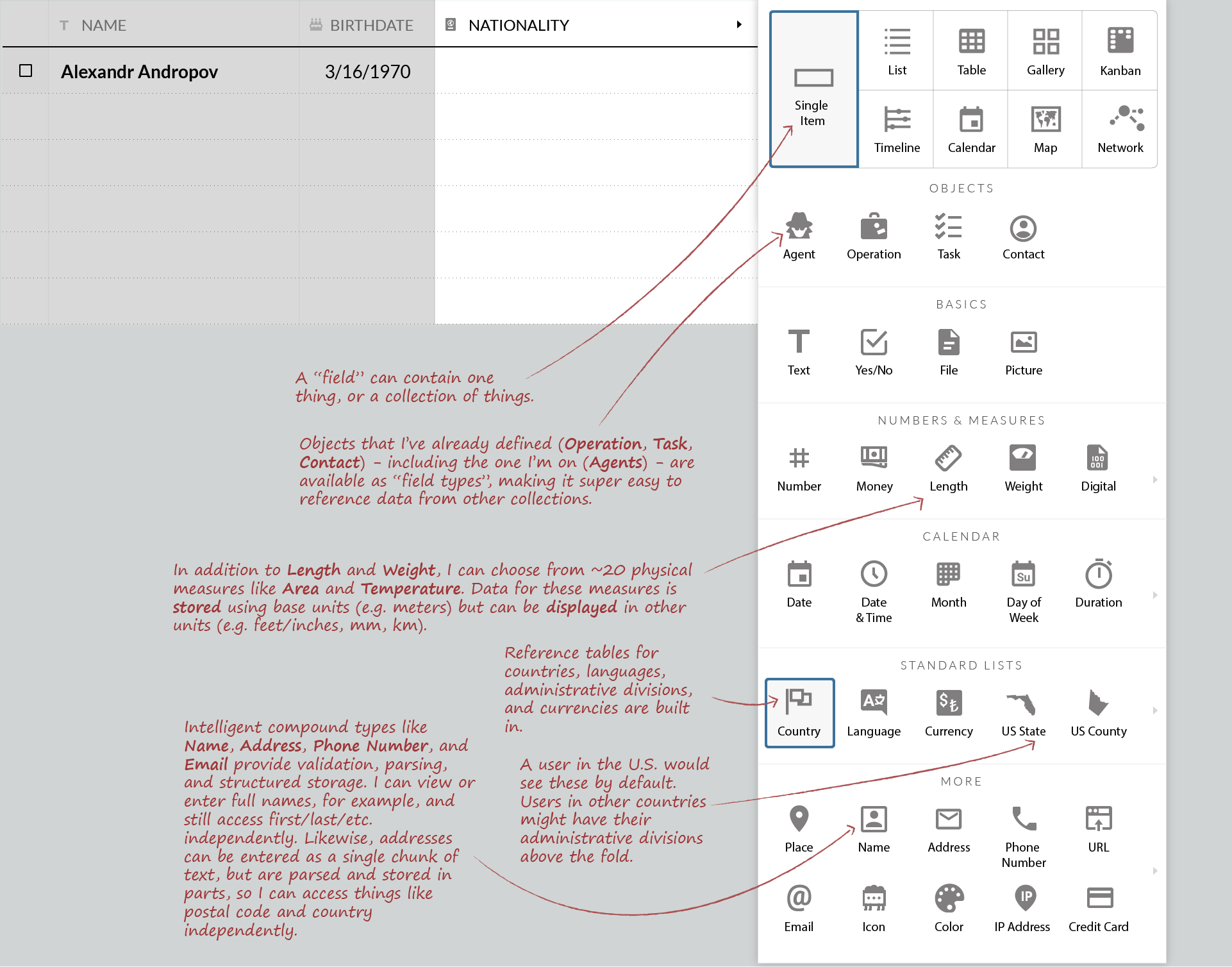

A humane system would take into account that (a) this is a really common scenario! and (b) we have standard lists for these things! — and make it easy to create a column with a datatype of Country or US State (or Canadian Province, or Kyrgyz Oblast, or what have you). Same goes for Currency and Language.

References to other things in the same system

One of the big limitations of spreadsheets is that it’s hard to link data from one table to another. Relational databases have this capability as a core strength — as the name implies — but as we’ve seen, most databases force us to think in an indirect and abstract way that doesn’t come naturally to most people.

This point — where Celeste realizes that what goes in a cell is actually a reference to a complex object that is defined elsewhere — is one of two key mind-melting junctures.

This shouldn’t be complicated.

Suppose I have a table of Classrooms and a table of Teachers. I want to assign a Teacher to each Classroom, so I make a column called Teacher. What’s the field type of that column?

It’s a Teacher.

What it’s NOT: A Link, a Reference, a Foreign key, or any other nerdy term that focuses attention the underlying implementation and makes it scary to civilians. Celeste shouldn’t have to decide whether this will be stored in a normalized or denormalized way. Celeste shouldn’t have to know an embedded document from a pointer. These are implementation details and they shouldn’t leak through to the UI.

Suppose I’m building a system that includes Tasks, Projects, Companies, Customers, and Employees. I should be able to treat each of these as a data type, and see them listed right there with all the other data types we’ve discussed. What goes in this field? A Company. Or a list of Employees.

Again, we’ve made this kind of thing straightforward and intuitive for ourselves as programmers. We’ve been living in an object-oriented world for over three decades now. We the have built-in primitives, yes, but we can define our own custom objects. Objects have properties that are in turn primitives or objects. This elegantly recursive paradigm makes it possible for us to model pretty much any real-world concept we can dream up, in all its detail and complexity.

So why don’t we put these tools in the hands of users?

Instead we restrict them to stupid grids and give them a handful of stupid datatypes to choose from. It ain’t right.

Collections of things

The elegance of the object model depends, crucially, on our ability to represent arrays of objects in addition to individual objects. So there might be multiple Employees working on one Project, or multiple Customers in the same Company.

This is the second mind-melting juncture for Celeste: How do we fit a list of things — or a whole other table — into this little cell?

Again, as programmers we have no problem modeling this. You can have a thing, or you can have an array of N things.

In the latter case, it’s easy to end up with a clunky UI. But that’s a solvable problem.

What’s required is a willingness to try, and a willingness to stop infantilizing the user.

Stop treating civilian users like babies

On that last point, a brief rant.

Since the early days of personal computing, we’ve made great progress towards making software easier to use. We’ve learned to say no to new features, we remind ourselves to Don’t Make Me Think, and we aspire to create software that does just one thing well.

That’s all healthy and positive — for the most part.

But I feel like one result of that has been that we software makers have collectively and individually ratcheted down our level of ambition. We’ve internalized a condescension towards end users that has led us produce more focused applications that do less and less, on the theory that anything more would overwhelm our poor customers.

As a result, there’s a huge chasm these days between what you can accomplish with user-facing tools and what you can accomplish by writing code.

Turns out, there are lots of intelligent non-programmers out there. There was a time — I know because I remember it — when there was tons of competition for that market. Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, there were dozens of innovative database systems designed for non-programmers to use: dBase. Hypercard. FileMaker.

Part of what happened, I think, was an accident of history: After Microsoft Office steamrolled the “office productivity” segment of the software industry, we were left with just two viable products in the user-facing database space: Excel and Access. Access has never sparked much enthusiasm or creativity, on account of it sucks and has always sucked. Excel has proved to be approachable and versatile enough that, in spite of not being a database, it has become the general-purpose database of choice. In doing so, it’s almost completely suffocated innovation in this space.

But those users are still out there, and I think they can be trusted with the concepts of arrays and objects and recursion.

It’s our job, as programmers, to offer up these facilities in a way that maps naturally to people’s intuitions; and there are a million ways to get that UX wrong. It’s our job to hide everything but what’s essential, to provide affordances, to avoid exposing distracting or intimidating implementation details. But it can be done, and it should be done, because it’s not right that all that creative energy is being wasted on twisting Excel into unspeakable contortions.

I’m going to stop there for now. Hopefully we’re a bit closer to having a tangible idea of what this tool might look like.

One possible way of presenting data types.

We want to make a tool that serves as a platform for humans to organize information for themselves and for teams they work on. To get there, I think we need to give a lot of thought to the types of data that humans are likely to organize. It believe it will be crucial not to dumb down this part down, but rather to use the familiar concept of the data type as a way of sneaking in the full flexibility and power of the object model.