Things have changed a lot in the decade since the last time I built a web application from the ground up. It used to be you picked a framework (ASP.NET, Rails, etc.) and learned it inside out. Now, as a result of the open source explosion in the JavaScript ecosystem, it’s your job to put together a mosaic of frameworks.

On the one hand, we’ve finally arrived at the promised land of code reuse. If you’re into programming productivity, no Agile methodology or VS Code extension compares to a technique I like to call “importing code that someone else wrote.” What a time to be alive!

Used with permission. Original here.

On the other hand, the framework anxiety depicted in this CommitStrip cartoon has multiplied into a fractal landscape of decisions both big and small.

Say you start by picking a front-end framework. For this project, React looks like an easy choice. It’s one of those rare technologies that makes everyone using it feel like a badass.

But React is just a rendering engine; its scope is minimalist by design. The ecosystem around it is vast and energetic, evolving at a dizzying speed. There are lots of choices to make and lots of alternatives at each juncture. And no matter how much time you put making educated decisions, there will probably be something better next week.

At some point, though, you have to stop thinking and start coding. I’ve spent the last couple of months experimenting with different approaches to different parts of the puzzle, and the outlines of an overall architecture are starting to take shape in a way that I’m really excited about.

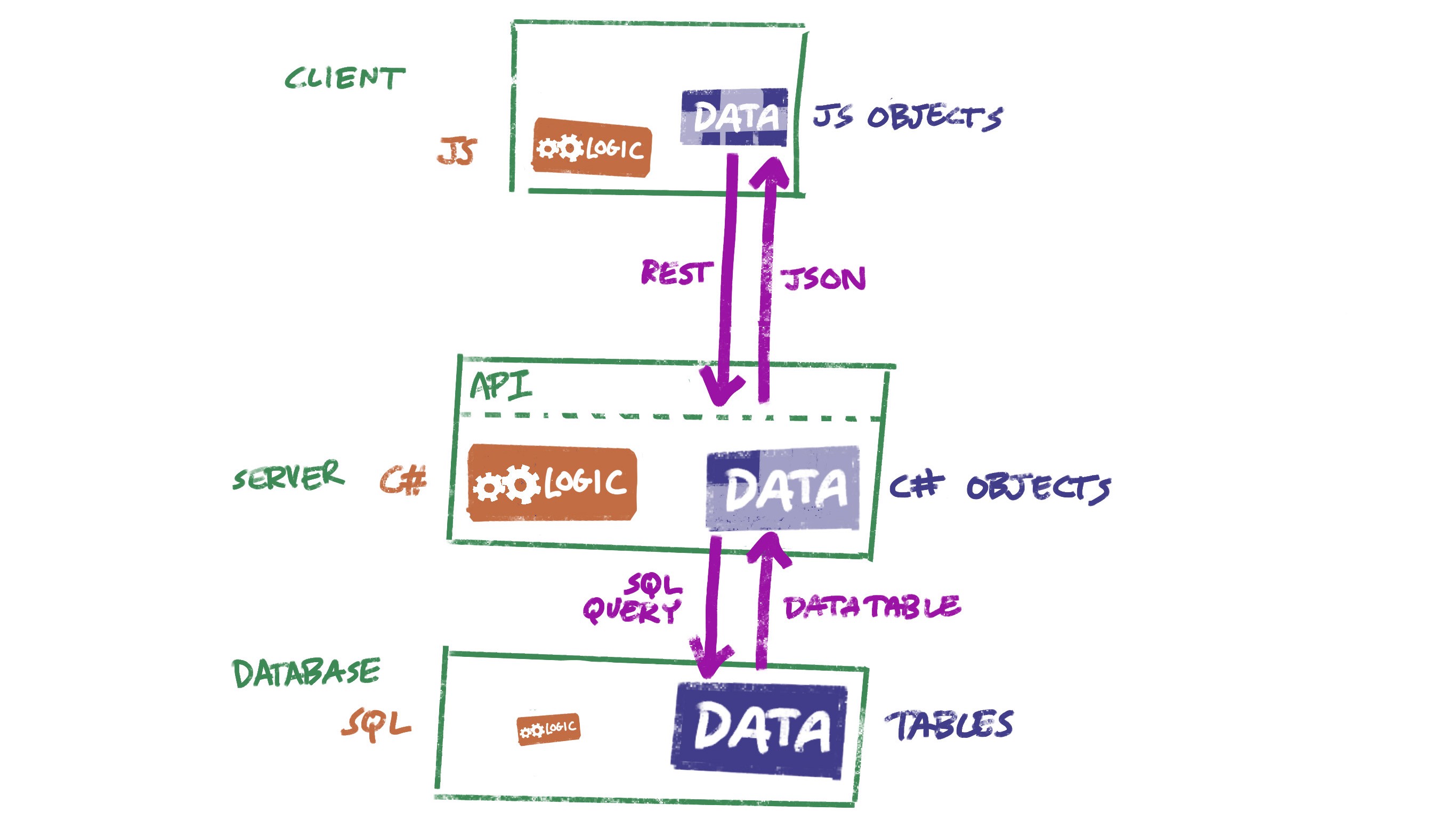

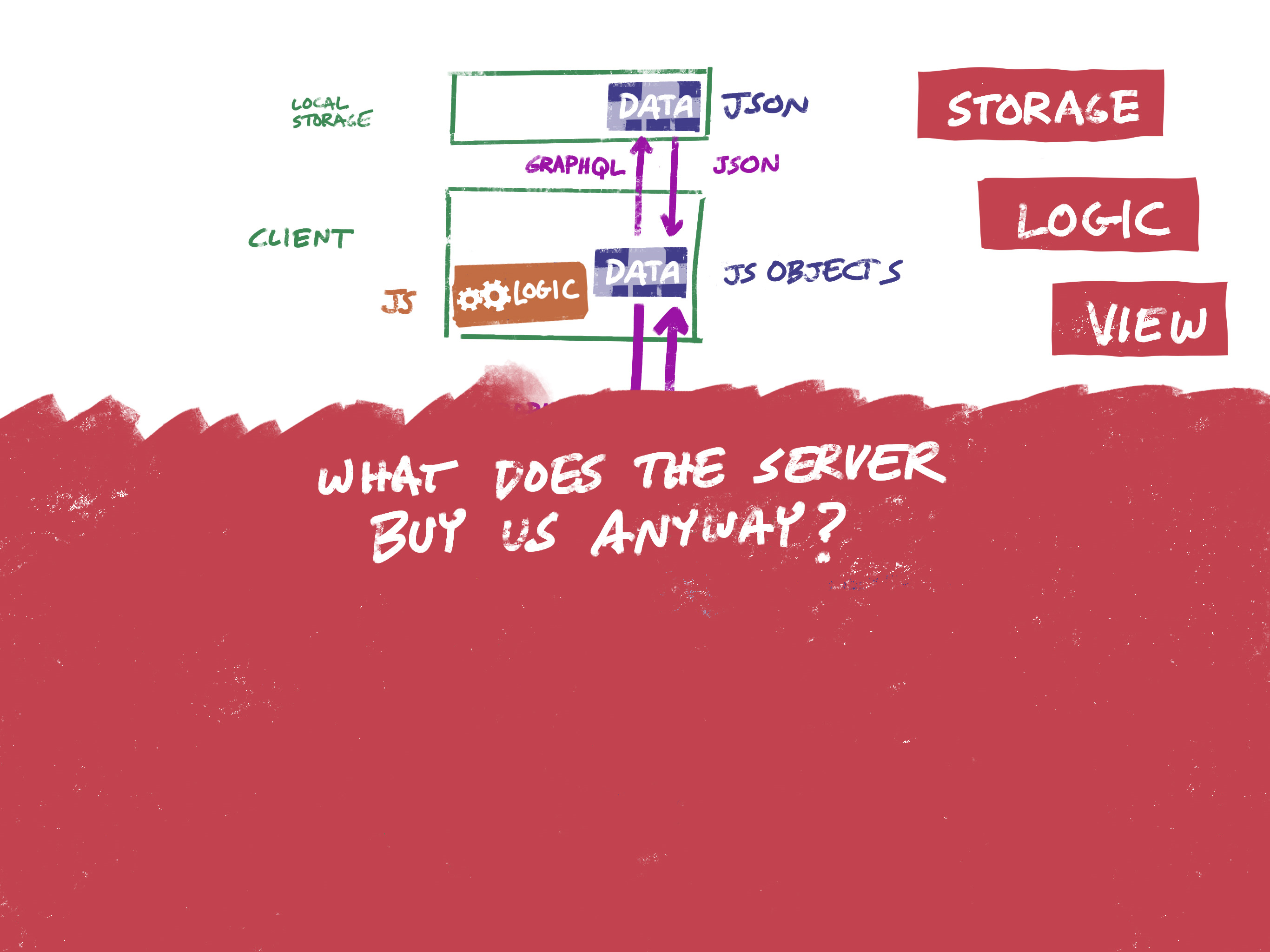

My starting point is the way DevResults works, so even though that’s a decade-old codebase, let’s take a look at its architecture. It’s a server application written in C#, a SQL database, and an Angular front end. So something like this:

Nothing surprising here — this is a very standard architecture for web apps of a certain age.

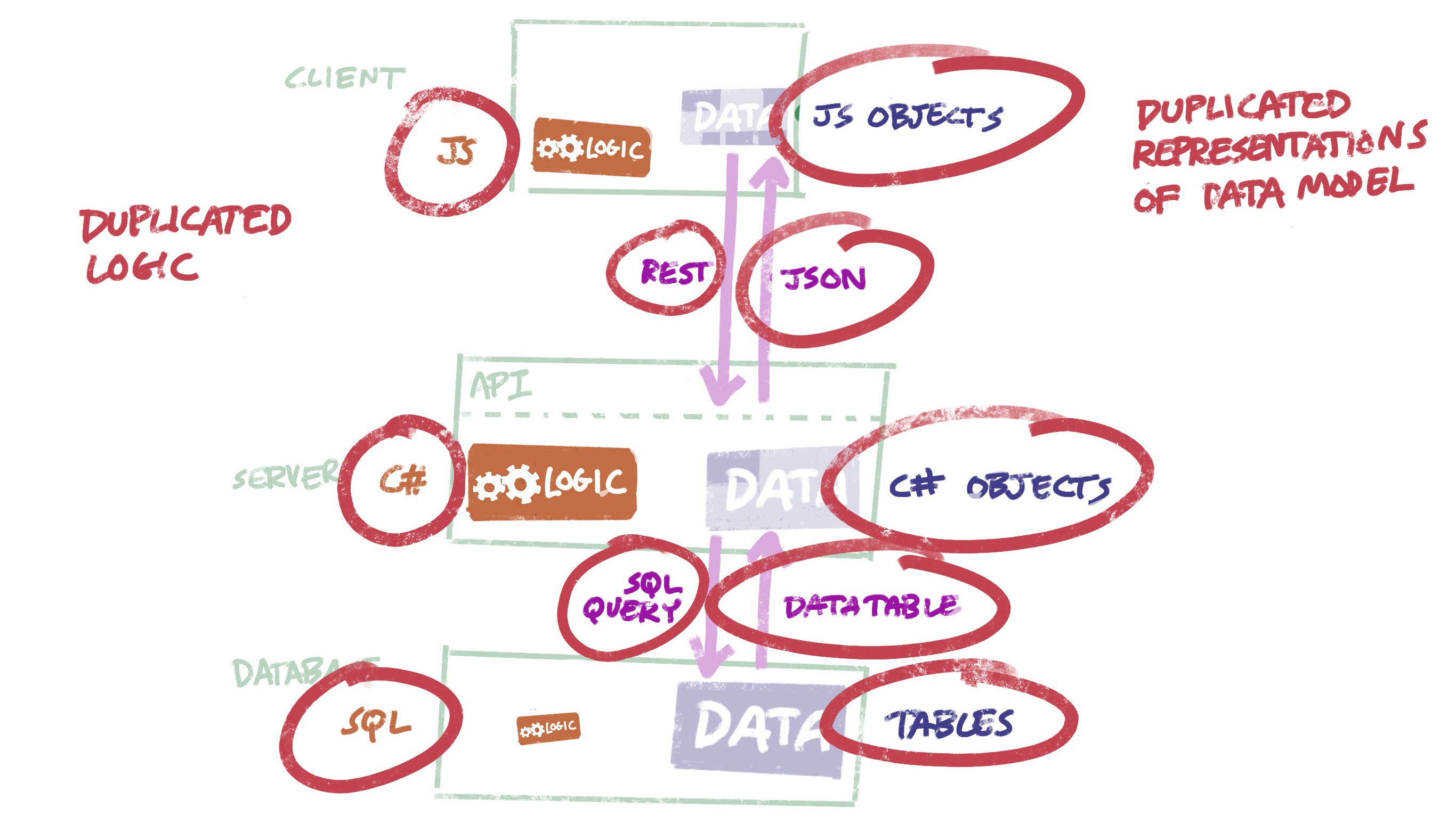

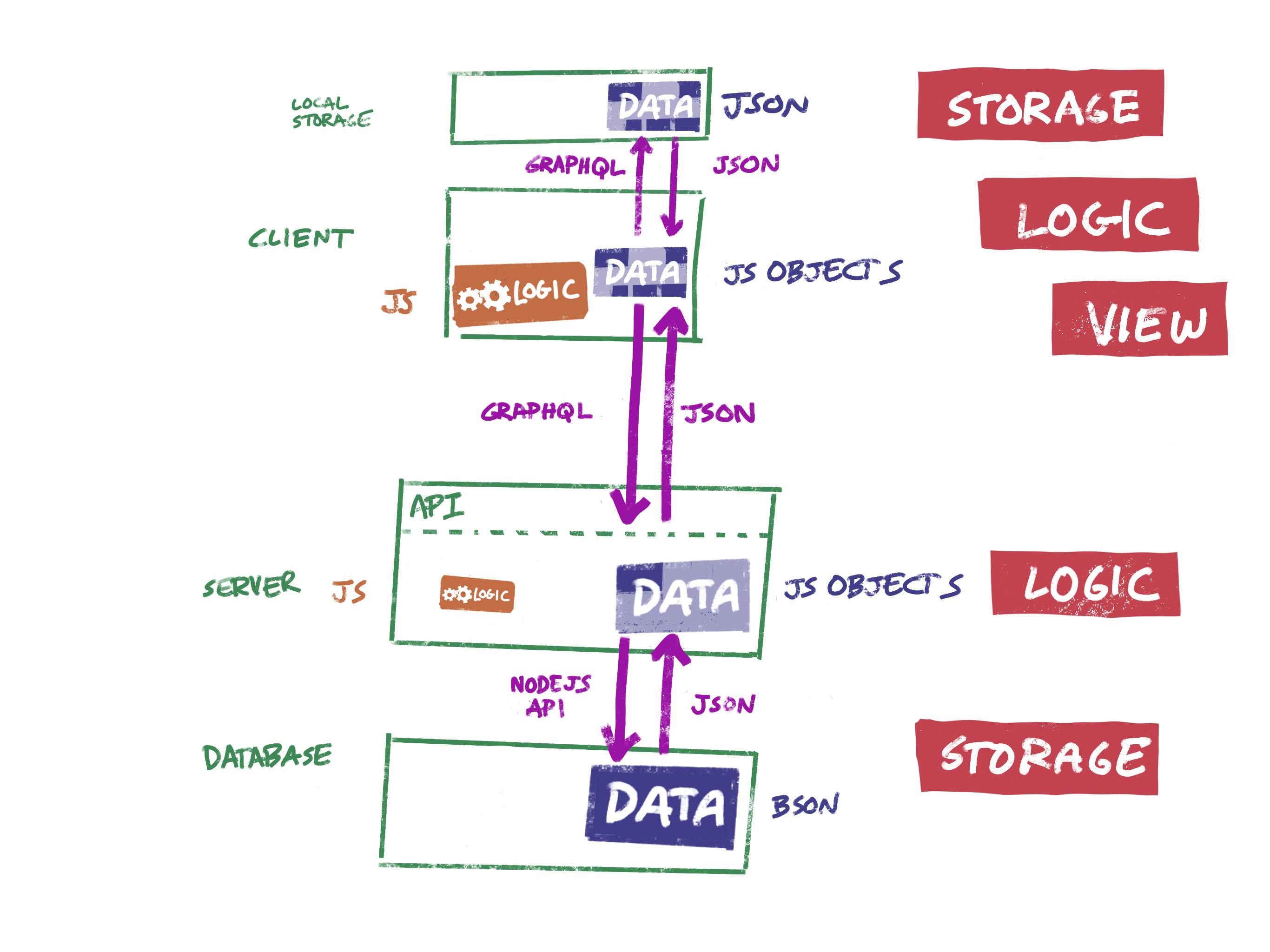

There are several sources of inefficiency here:

- JavaScript, C#, and SQL are very different worlds, and some large fraction of the code we write and debug is just about the mechanics of unpacking information from one form and repackaging it into another.

- Our data model has to be restated repeatedly in multiple different formats.

- Each of these layers includes some logic, and it’s hard to avoid duplicating some logic across more than one layer.

Kind of a mess: Logic expressed in 3 languages, data model expressed lots of different ways.

Now, DevResults was first written in 2009, and changes to the code since then have had to be made in a cautious and incremental way in order to avoid disrupting people who actively use the software. We’re starting with a clean slate now, so what should we do differently?

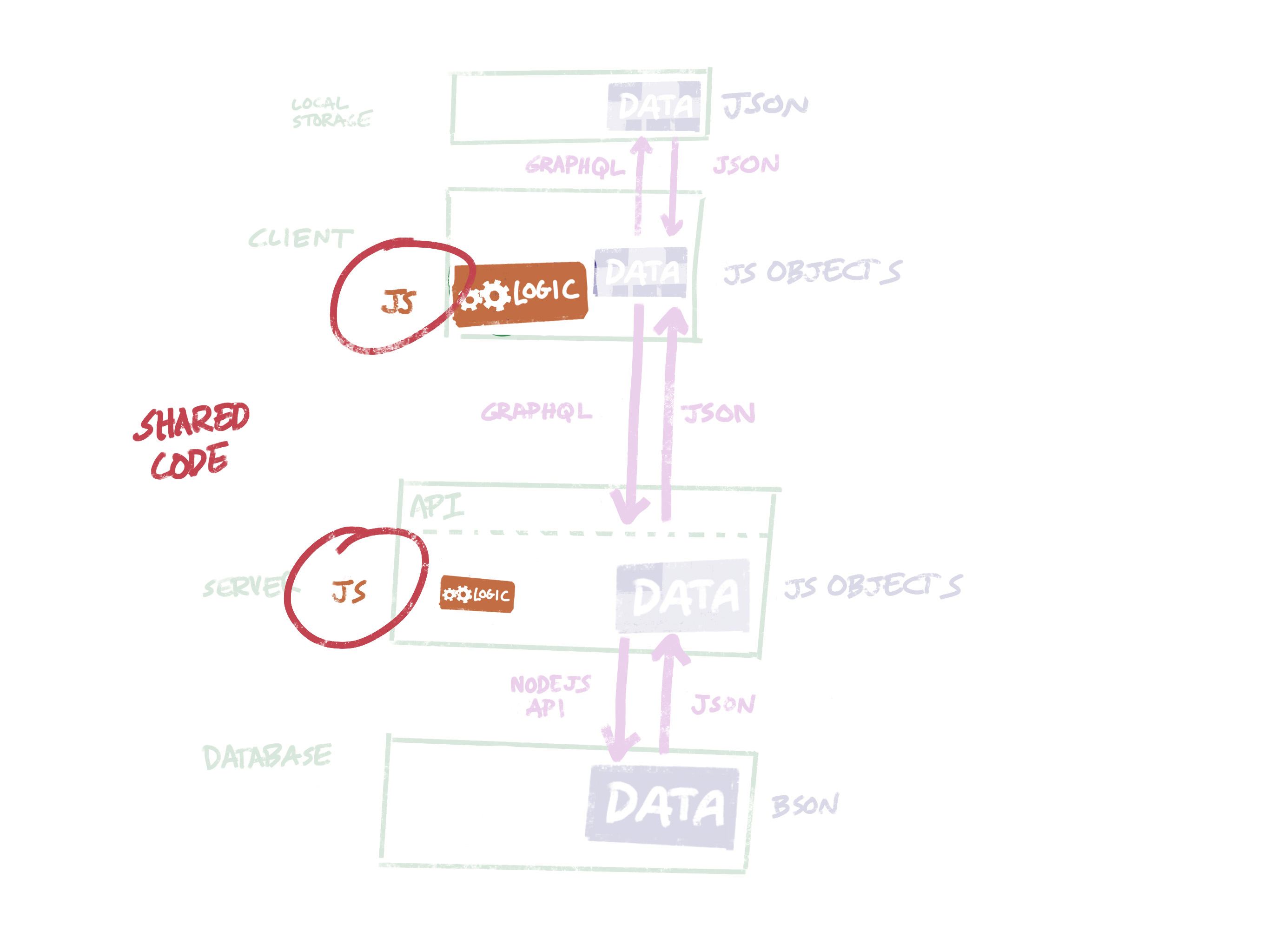

Improvement 1: JavaScript everywhere

The first step to simplify this is to use a single language for the codebase. In 2018, the only reasonable choice is JavaScript. We can use Node.js on the back end, and that way bits of logic that are shared between the client and the server only have to be written once.

Better: Server-side JavaScript lets us write code around the data model just once, and run in both places.

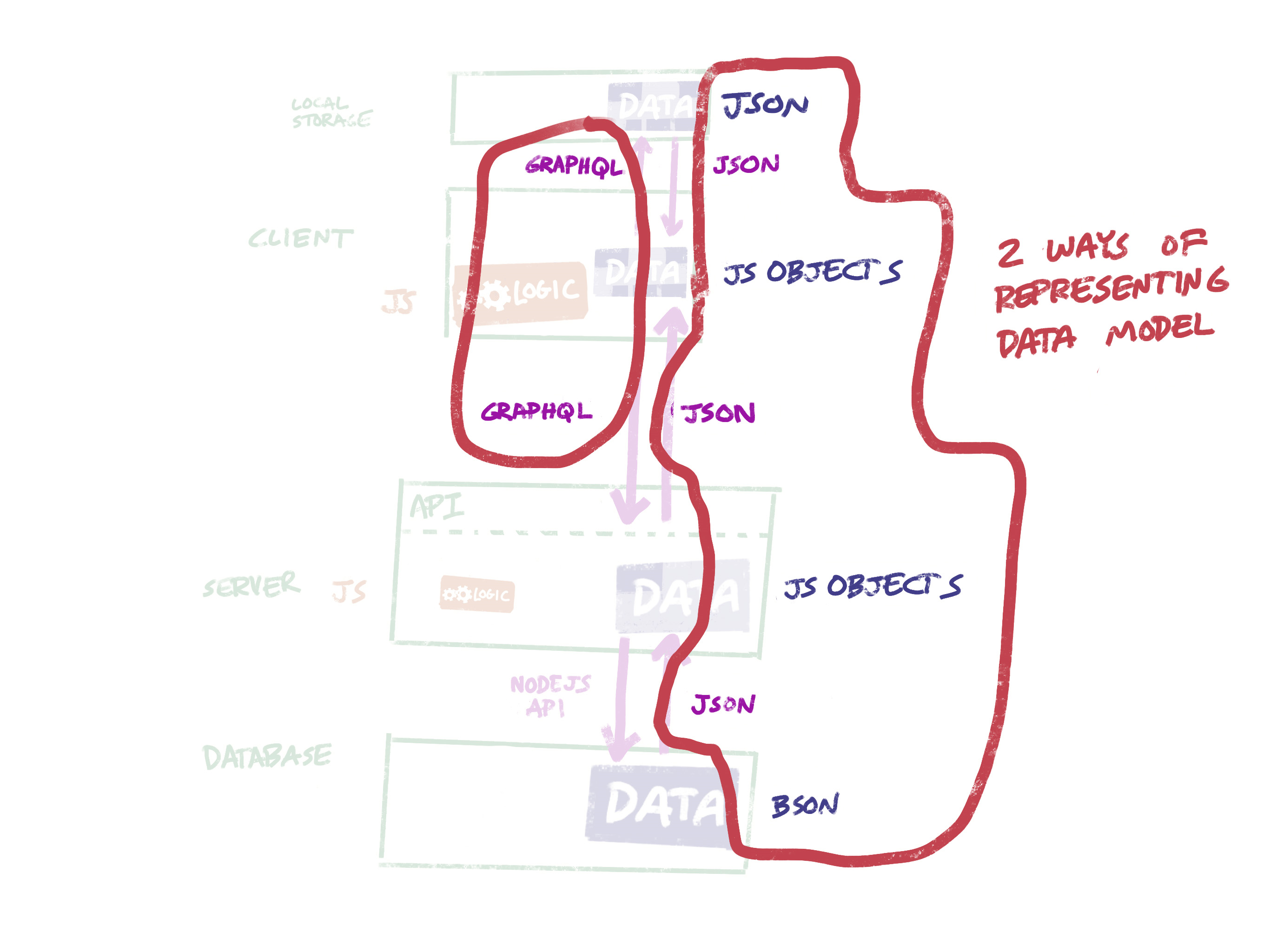

Improvement 2: JSON everywhere

We can also use a NoSQL database like MongoDB, which accepts and returns JSON data. So our data can move from client to server to database without having to be translated.

Better: GraphQL for requesting data, JSON for representing data.

Another simplification is to use GraphQL instead of REST to communicate requests for data. In fact, if we use Apollo’s client framework, we can use GraphQL to query local state and locally cached data in addition to server data. That leaves us with just two representations of the data model, which is a big improvement.

So far, so good. There’s nothing revolutionary here; in fact something like this architecture is rapidly becoming the norm for new projects.

And yet…

But when I started playing with this in a couple of toy apps, I was still frustrated by the number of moving parts, and the consequent amount of ceremony required just to do simple things.

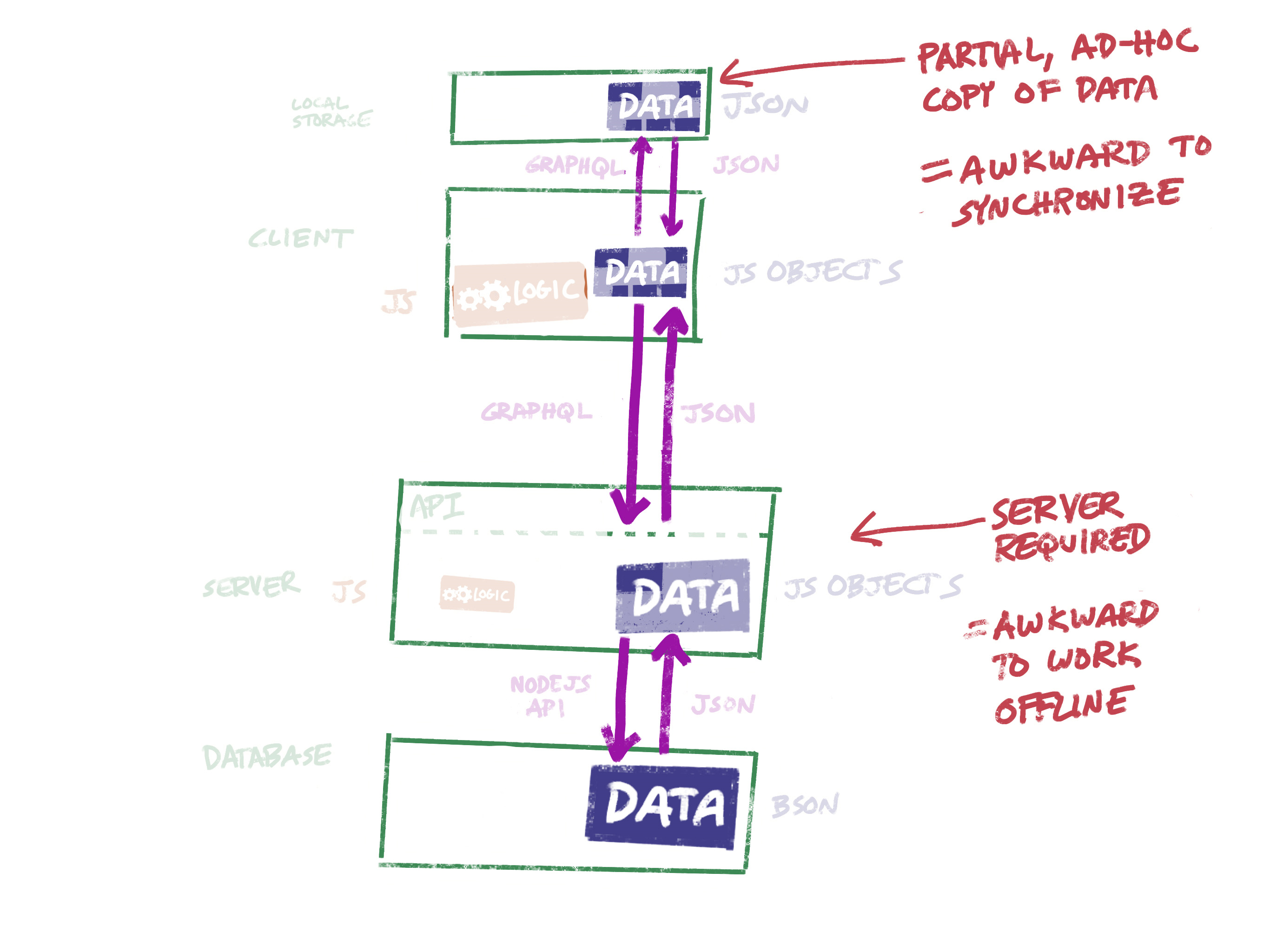

- Data storage is provided by the database. But since the client needs to work offline, it needs to provide storage also. That means you need to write two data layers — one for the client to work with local data, the other for the server to work with the database.

- Application logic traditionally lives on the server. But if the client needs to work offline, some or all of that logic needs to be on the client as well.

Is there a good reason for all of this duplication?

So we’re duplicating logic between the server and the client, and duplicating storage between the database and the client.

But when I really ground to a halt was when I started thinking about how to support a user who is disconnected from the server.

Thinking offline-first

We all spend a certain amount of our time offline or on spotty networks. For those of us who live in bandwidth-saturated cities in the rich world, that’s primarily when we’re traveling. For many DevResults customers, who are trying to get things done in remote corners of some of the poorest countries on earth, working offline is a fundamental necessity.

Excel, for all its faults, doesn’t care whether you’re offline or online. If we really want to liberate people from spreadsheets, we need to be able to provide first-class support to the offline scenario.

There are two big challenges with building an app that works offline:

- It has to work when no server is available (duh), which means that it needs to have a full local copy of the data that it needs.

- When the app does go back online, it needs to reconcile changes that have been made locally with changes that have been made elsewhere.

The standard browser/server/database model isn’t well-suited to offline scenarios.

Long story short, this isn’t the architecture you would start with if offline usage is a priority. It might be possible to bolt on offline capabilities after the fact, but it wouldn’t be easy and it wouldn’t be pretty.

Since we are starting from scratch, we can do better. But we’ll have to rethink things at a more fundamental level.

How did we get here?

This is the sort of kludge that you get when you’re at a very specific and awkward juncture in the history of technology.

Specifically: Since the invention of the computer, the pendulum has swung every few years from putting intelligence on the server, to putting it on the client, and back again. Most recently, we’ve gone from dumb terminals running software on a mainframe, to PC operating systems with software installed, to software as a service delivered in the browser.

The original web applications ran entirely on the server, and the browser was just a dumb terminal. Each interaction caused the server to re-render a fully-formed HTML page and send it to the browser. In 2005 AJAX became a thing, allowing us to avoid some of those round trips. Ever since then we’ve been moving intelligence back to the client in bits and pieces.

More than a decade later, you can do pretty much anything you want within a browser, and even more if you give the browser big-boy pants by wrapping it in Electron. But we’re still living with a lot of assumptions that come from the days of server-side rendering.

What if we only had a client?

Let’s take a step back and think about what a “web application” with no web server would look like.

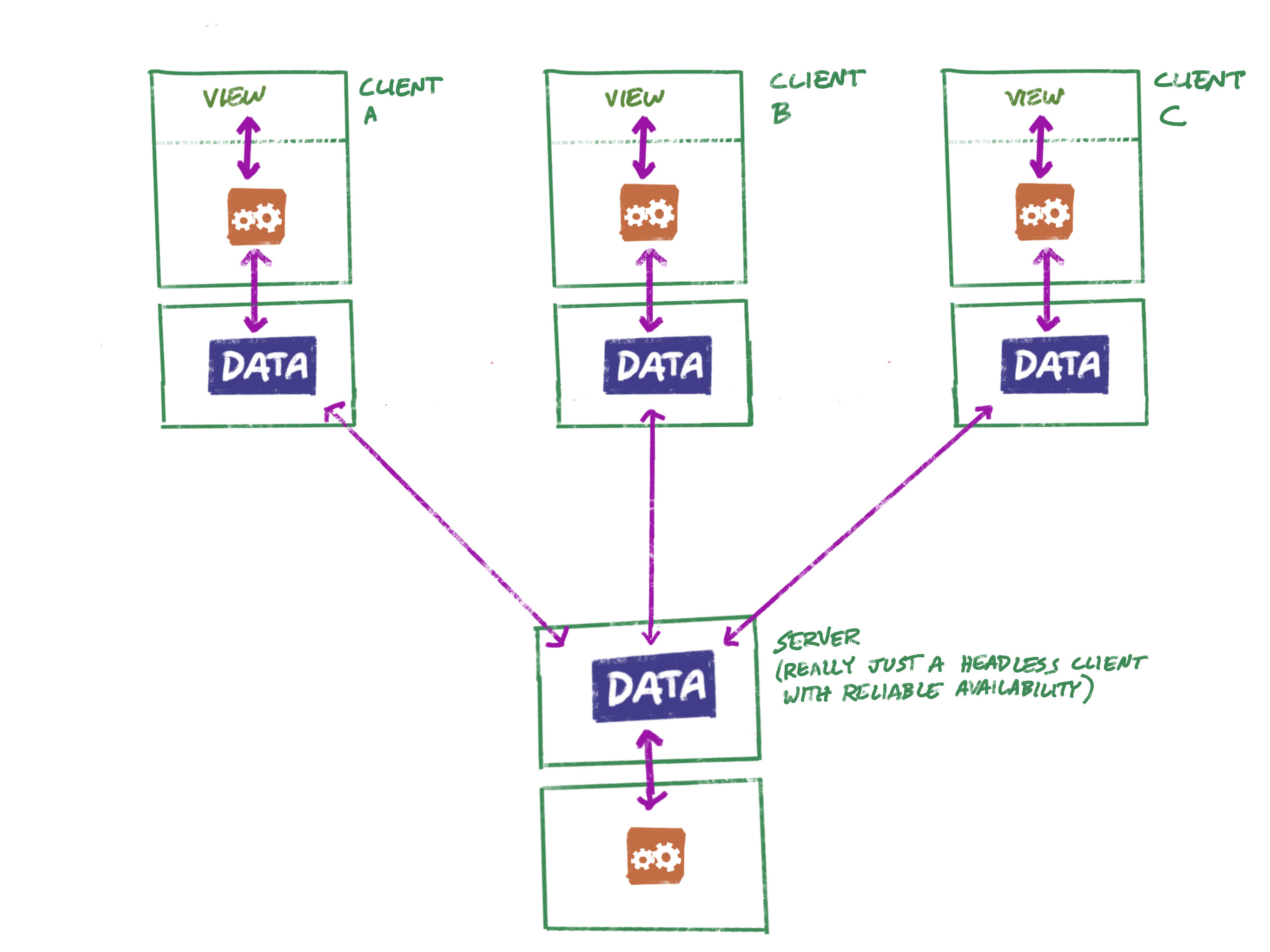

The most obvious answer is that we need the server to collaborate with others. If you’re the only one involved in whatever you’re working on, you may not need a web app. But if you’re working with a team of two or more people, you want some way of keeping everyone on the same page, and centralizing the data on a server is an obvious way of doing that.

So, yes, this would be a very simple architecture:

Simple, but not very useful.

But Herb, I hear you saying: This is of no use to us if Client A (Alice) and Client B (Bob) need to collaborate.

So let’s put on our “pretend it’s magic” hats.

Let’s just imagine for the moment that we had a magical way of automatically and instantaneously synchronizing Alice’s data with Bob’s data, so that when they’re both online, they’re both always looking at the same thing.

Simple, but you have to believe in magic.

If we had that magical piece, then we’d truly be able to eliminate duplication in our codebase.

But wait, you say! This peer-to-peer setup requires Alice and Bob to be online at the same time. If Alice makes some changes and then goes offline, Bob won’t see them the next time he comes online.

OK, no problem — we can just fire up a client on a computer that no one uses, and leave it running all the time.

Congratulations, we’ve just re-invented the server! 😆

Except this server is really just a special instance of our client — one that no one uses directly, and that lives on high-availability infrastructure.

Our headless-client-as-server doesn’t require a separate codebase. Compared to a traditional server, it can be hosted in an inexpensive, highly redundant, and infinitely scalable way: Each instance could live inside an lambda function, automatically scaled as needed, and backed by a simple key-value persistence layer.

OK, that’s great, but at some point we’re going to have to have to come up with a solution that keeps everyone’s data consistent without relying on magic.

As you might suspect, data replication and synchronization is a problem that a lot of smart people have been thinking about for many years; so not only do we not have to rely on magic, but we don’t have to invent anything new.

Mutable data, immutable data, and the meaning of truth

The solution hinges on a different conception of data from the one I’ve always worked with.

The databases I’ve always worked with treat data as mutable: If you need to update data, you replace what was there with something new. So when I moved from Washington DC to Barcelona, some database might have reflected the change by replacing a value in the City column for my record:

In this case, you could go back and look at the log of changes to see, for example, that an entry was made in 2012 stating that I lived in Washington DC, and that in 2016 that entry was updated to Barcelona.

In fact, using that log, we could theoretically reconstruct the state of the database at any point in time — but it would be clumsy. In a traditional database, the state of a given table right now is our source of truth, and the change logs are ancillary metadata.

But suppose you have two replicas of this database, and they’re both intermittently online. At some point we compare them, and one says I live in Washington while the other says I live in Barcelona. How do we know which one is true? Without any additional information, we have no way of knowing.

This perspective is what makes replication and synchronization complicated. Our source of truth is a moving target.

The inside-out database

What if we reverse our perspective, though, and think of the change log as our primary data source? In that case a snapshot of the data at any point in time is just a pure function of the event log.

The event log shows these two facts:

- In 2012, Herb said he lived in Washington DC

- In 2016, Herb said he lived in Barcelona

Both of these statements are true facts, and we can easily query them to derive a picture of the state of the world at any given moment t. Now we can see that the current state of the world is just a special case, where t = now.

With this perspective, much of the complexity around replication and synchronization just disappears. CRUD (create/read/update/delete) is now just CR, because updates and deletes are just another kind of new information. It’s much easier to merge two event streams than it is to merge two conflicting point-in-time snapshots.

Now, this all just clicked for me, and I’m super excited about it. But it’s nothing new: The abstraction of append-only logs and immutable data stores has been with us for a while.

- Double-entry bookkeeping is perhaps the original append-only log. If there’s an error in a previous entry, we don’t go back and correct it in place: We make a new adjusting entry.

- This is exactly how Git, Mercurial, and similar source-control management systems solve the problem of asynchronous, distributed collaboration: by storing a sequence of changes, and deriving point-in-time snapshots from those changes.

- Redux, the widely-used state container for JavaScript apps, treats data as immutable, which makes “time travel” possible and makes it easy for frameworks like React to detect updates.

- Conflict-free replicated data types (CRDTs) are data structures that can be replicated across multiple computers, that can be concurrently updated, and that resolve any resulting conflicts in a predictable, consistent way.

- And, of course, the blockchain is a distributed append-only log, with the added twist of cryptographically-verified consensus to verify correctness.

I’m going to focus on the next-to-the-last item in that list — CRDTs — because they abstract away the problem of reconciling conflicting changes.

CRDTs and Automerge: Indistinguishable from magic

Automerge, a JavaScript implementation of a CRDT, promises to be the magical automatic synchronization and conflict resolution layer we’re looking for.

Automerge is essentially a wrapper for JavaScript objects that enforces immutability, provides an interface for committing changes, and automatically resolves conflicting changes.

The simplest way to think about Automerge is that it’s just like Git, for JSON data — except without merge conflicts.

- Just like Git, each user has a local copy of the data, and can commit changes whether or not they’re online.

- Just like Git, when there’s a network connection, changes can be pushed, merged, and pulled so that everyone ends up with the same state.

- Just like Git, users can choose to work alone, or to collaborate peer-to-peer, or via a central hub.

However:

- Unlike Git, merge conflicts are automatically resolved in an arbitrary but predictable way, so that everyone ends up in the same state without any further intervention (hence the “Auto” in “Automerge”).

The idea of automating conflict resolution is the part of this that’s most likely to raise eyebrows, so let’s look at that a bit more closely.

- First of all, a CRDT uses an algorithm to resolve conflicts that is arbitrary and deterministic. To be clear, it’s not random: If it were, then different users could end up in different states. It’s also not based on any clocks, since we can’t ensure that any two users’ clocks show the same time. For example, you might use the sort order of a hash of the change data to determine the order “wins”. The only requirement is that all users can independently make the calculation and arrive at the same result.

- Conflicts are resolved in a non-destructive way, preserving information about the conflict as metadata. This way, if needed, the application can apply its own conflict-resolution logic after the fact, or surface conflicts to a user for human resolution.

- Conflict resolution is rarely necessary in most use cases. If two different objects are modified, or different properties of the same object are modified, there is no conflict. If two users simultaneously insert or delete items in an array (or characters in a text document), all insertions and deletions are preserved. There is only a conflict when there are concurrent changes to the same scalar property on the same object.

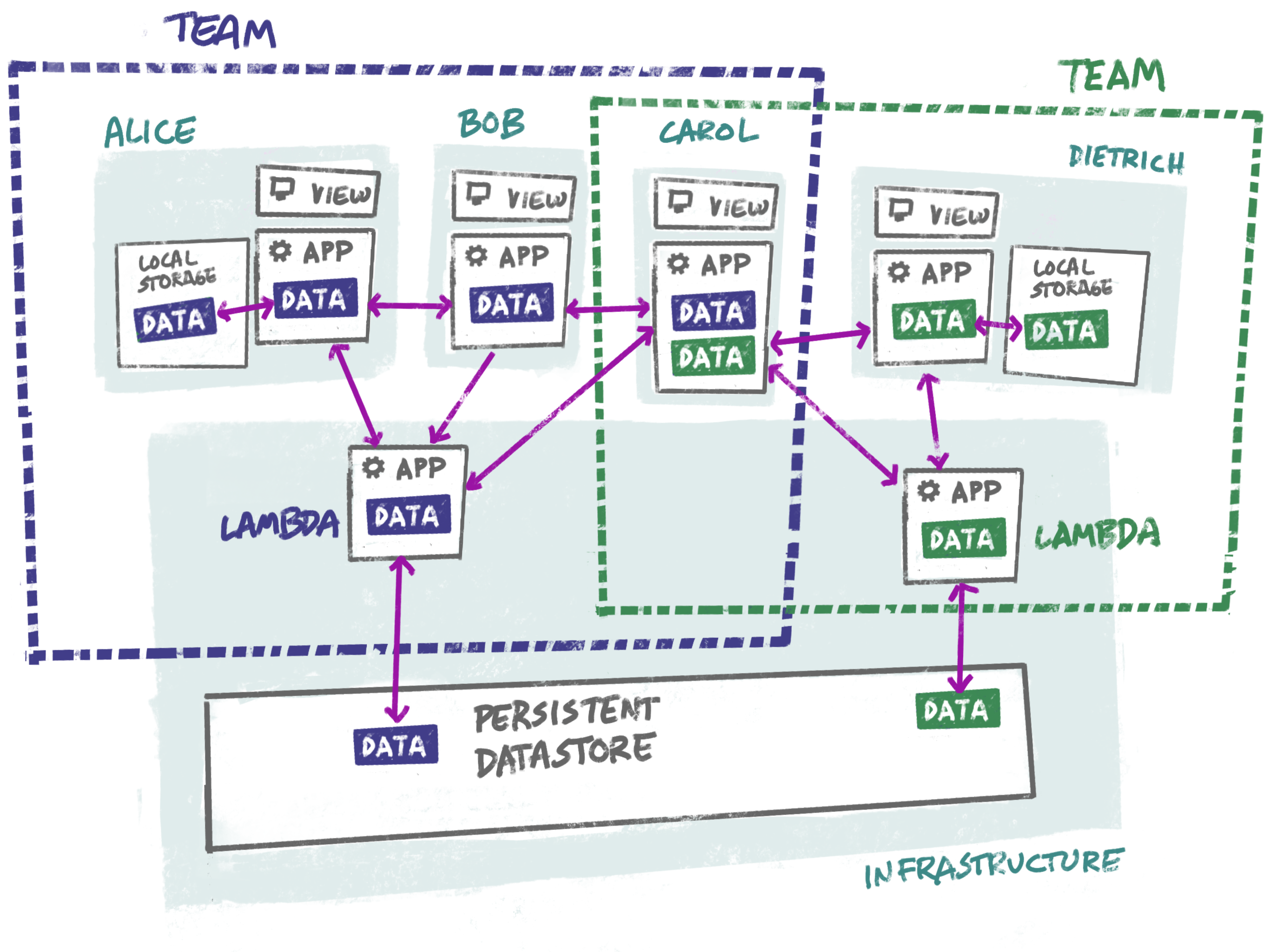

So the overall idea starts to look like this:

- Instead of a traditional browser/server/database stack, we have a single application that can work as a standalone thing, persisting its data in a local or remote key-value store, and optionally synchronizing its data with other instances.

- Real-time background synchronization is provided automatically and unobtrusively by Automerge.

- Instead of a server, we have an always-available headless peer living in a lambda function. If we define a “team” as our permissions boundary, it might make sense to just spin up one lambda per team.

This is a very different design from the ones I’ve worked with in the past. It’s not the way most software is being written today. But I’m convinced that many applications will be architected this way in the future. The advantages are hard to ignore:

- Users can work with the application offline or online.

- The application is always working directly with local data, eliminating network latency from most use cases.

- Users can decide whether they want to work alone, collaborate on a peer-to-peer basis, or use a server as a central hub.

- If a central server is needed, it is cheap, low-maintenance, and super scalable.

- Users can easily roll their data back to any point in time, or review an audit trail of who made what changes when.

- Developers can work with a vastly simpler stack, with no duplication, no impedance mismatches and fewer possible points of failure — making it easier, cheaper, and faster to develop new functionality.

There are trade-offs involved that are going to be deal-breakers for some scenarios. For example, this setup doesn’t make sense for big datasets — specifically any datasets that are too big to store on a single computer. In practical terms, today, this probably means an upper limit somewhere between 10GB and 1TB, depending on the target market. That upper limit will rise exponentially in a predictable way; but this will never be a “big data” solution.

For the purposes of this application, that’s OK. Remember, we’re talking about a tool to allow teams and individuals to organize their own information. Our competition is a bunch of spreadsheets.

Also, I haven’t mentioned authentication and permissions. Unlike a traditional database, Automerge assumes those concerns are handled elsewhere. I have some thoughts, but I’ll leave those to a later post.

Is this insane? Has it been done before? Let me know what you think!

Further exploration

In Distributed Systems and the End of the API (2014), Chas Emerick points out that network API models — whether RPC, SOAP, REST (or now, GraphQL) — are fundamentally unsuited to distributed systems, and that many API use cases can be solved using CRDTs instead.

The earliest and clearest explanation of the advantages of immutable event logs I found is in the article How to beat the CAP theorem (2011) by Nathan Marz. Martin Kleppman takes a very similar line in the talk Turning the database inside-out with Apache Samza (2015).

Martin Kleppman is also the author of Automerge, which he presents in a very accessible way in the talk Making servers optional for real-time collaboration (2018).

Automerge was built under the auspices of Ink and Switch, an industrial research lab founded by Adam Wiggins, one of the co-founders of Heroku, along with Heroku veterans Peter van Hardenberg and Mark McGranaghan.

Ink and Switch has also created a series of proof-of-concept apps using Automerge:

- Trellis, a peer-to-peer Trello clone

- Pixelpusher, a collaborative drawing tool

- Pushpin, a collaborative corkboard app