Almost two decades ago, Joel Spolsky excoriated Netscape for rewriting their codebase in his landmark essay Things You Should Never Do.

He concluded that a functioning application should never, ever be rewritten from the ground up. His argument turned on two points:

- The crufty-looking parts of the application’s codebase often embed hard-earned knowledge about corner cases and weird bugs.

- A rewrite is a lengthy undertaking that keeps you from improving on your existing product, during which time the competition is gaining on you.

For many, Joel’s conclusion became an article of faith; I know it had a big effect on my thinking at the time.

In the following years, I read a few contrarian takes arguing that, under certain circumstances, it made a lot of sense to rewrite from scratch. For example:

- Sometimes the legacy codebase really is messed up beyond repair, such that even simple changes require a cascade of changes to other parts of the code.

- The original technology choices might be preventing you from making necessary improvements.

- Or, the original technology might be obsolete, making it hard (or expensive) to recruit quality developers.

The correct answer, of course, is that it depends a lot on the circumstances. Yes, sometimes it makes more sense to gradually refactor your legacy code. And yes, sometimes it makes sense to throw it all out and start over.

But those aren’t the only choices. Let’s take a quick look at six stories, and see what lessons we can draw.

(Bonus: ASCII art summaries of each story!)

1. Netscape

Netscape ... 🡒 4.0 🡒 📝5.0 ☠ 6.0 🡒 7.0 🡒 ☠

⤷ Mozilla 1.0 🡒 ☠

📝Firefox 1.0 ---------- 🡒

Key: 📝 = rewrite ☠ = dead end

Netscape’s disastrous 5.0/6.0 rewrite is the original poster child for “never rewrite”, thanks to Joel.

Netscape’s Navigator, first released in 1994, defined the early years of the commercial internet. Less than two years after it was released, the company’s $3-billion IPO launched the dot-com era.

Netscape’s first serious competition came from Microsoft’s Internet Explorer, which came out in 1996.

At the beginning of 1998, Netscape was still the leading browser, but just barely. Netscape’s retail price was $49; Microsoft was giving IE away for free and shipping it with Windows as the default browser.

After version 4.0 of Netscape was released, the company announced that version 5.0 would be given away for free, and developed by an open source community created and funded by the company, called Mozilla.

This was basically unprecedented at the time, and Netscape won a lot of goodwill for making a gutsy move. As it happened, though, the community didn’t really materialize. Jamie Zawinski, one of the browser’s earliest developers, explains:

The truth is that, by virtue of the fact that the contributors to the Mozilla project included about a hundred full-time Netscape developers, and about thirty part-time outsiders, the project still belonged wholly to Netscape.

The team concluded that one reason outside developers weren’t interested in contributing to their open-source project was that the existing codebase was a mess:

The code was just too complicated and crufty and hard to modify, which is why people didn’t contribute … which is why we switched to the new layout engine. A cleaner, newly-designed code base, so the theory went, was going to be easier for people to understand and contribute.

Starting with a clean sheet

So after a year the group decided to scrap their work on 5.0 without releasing it, and started from scratch on version 6.0.

Another two years went by before Netscape 6.0 was finally released; and even after all that time it was clear that it still wasn’t ready to have been released. According to New York Times’ reviewer David Pogue, it took a full minute to start up (!) and hogged memory. And it lacked a number of simple usability features that previous generations of the browser had:

The print-preview feature is gone, as is the ability to drag a Web site’s address-bar icon directly into the Bookmarks menu. You can no longer copy or paste a Web address in the Address bar by right-clicking there, either. And you have to resize the browser window every time you begin surfing; Navigator doesn’t remember how you had it the last time you ran the program. The most alarming flaw, however, is that you can’t highlight the entire Address bar with a single click.

Not that it mattered. In the three years that Netscape stood still, Internet Explorer had taken all of its remaining market share:

When the rewrite began, Netscape was losing ground quickly to Microsoft’s Internet Explorer. When the new browser was finally released three years later, it was buggy and slow; meanwhile Netscape’s market share had dwindled to practically nothing. (Chart adapted from Wikipedia.)

In 1999, while the rewrite was underway, AOL had acquired Netscape in a deal valued at $10 billion.

Just two years after Netscape 6.0 was released, the Netscape team within AOL was disbanded.

Mozilla, the open-source community that Netscape had created, would go on to release the Firefox browser in 2002 — after yet another ground-up rewrite. Firefox did manage to gain back some market share from Microsoft.

But Netscape as a business was dead. (In a humiliatingly ironic footnote, Microsoft would end up with the remains of Netscape’s intellectual property after a 2012 deal with AOL.)

Having won that battle, Microsoft pulled back on its investment in browser technology. Internet Explorer 6.0 was released in 2001 and didn’t get another upgrade for another five years, in what some see as a deliberate strategy to prevent the web from advancing as platform for applications.

Lessons

People have argued that the rewrite wasn’t a disaster in the long term, because the project eventually led to the Gecko engine and the Firefox browser.

But we all had to endure years of stagnation in web technology under IE6’s endless, suffocating monopoly while we were waiting for new browser to gain traction; and what finally ended the IE6 era wasn’t Firefox but Google Chrome.

And anyway, the question at hand isn’t whether the rewrite was good for the web; it’s whether it was a good decision from the perspective of the company making the decision. Netscape’s slide into irrelevance wasn’t entirely due to the rewrite — a court agreed that Microsoft had deliberately abused their monopoly.

But the rewrite was certainly a contributing factor, and the end result was the destruction of a company worth billions of dollars and thousands of layoffs. So I’m going to agree with Joel that the net consequences of this rewrite were disastrous.

2. Basecamp

Basecamp Classic --------------------------------------------- ->

📝Basecamp 2 ------------------------------------- ->

📝Basecamp 3 ------------------------- ->

In the early 2000s, a Chicago web design company called 37signals had built a following around founders Jason Fried and DHH’s influential and often contrarian blog.

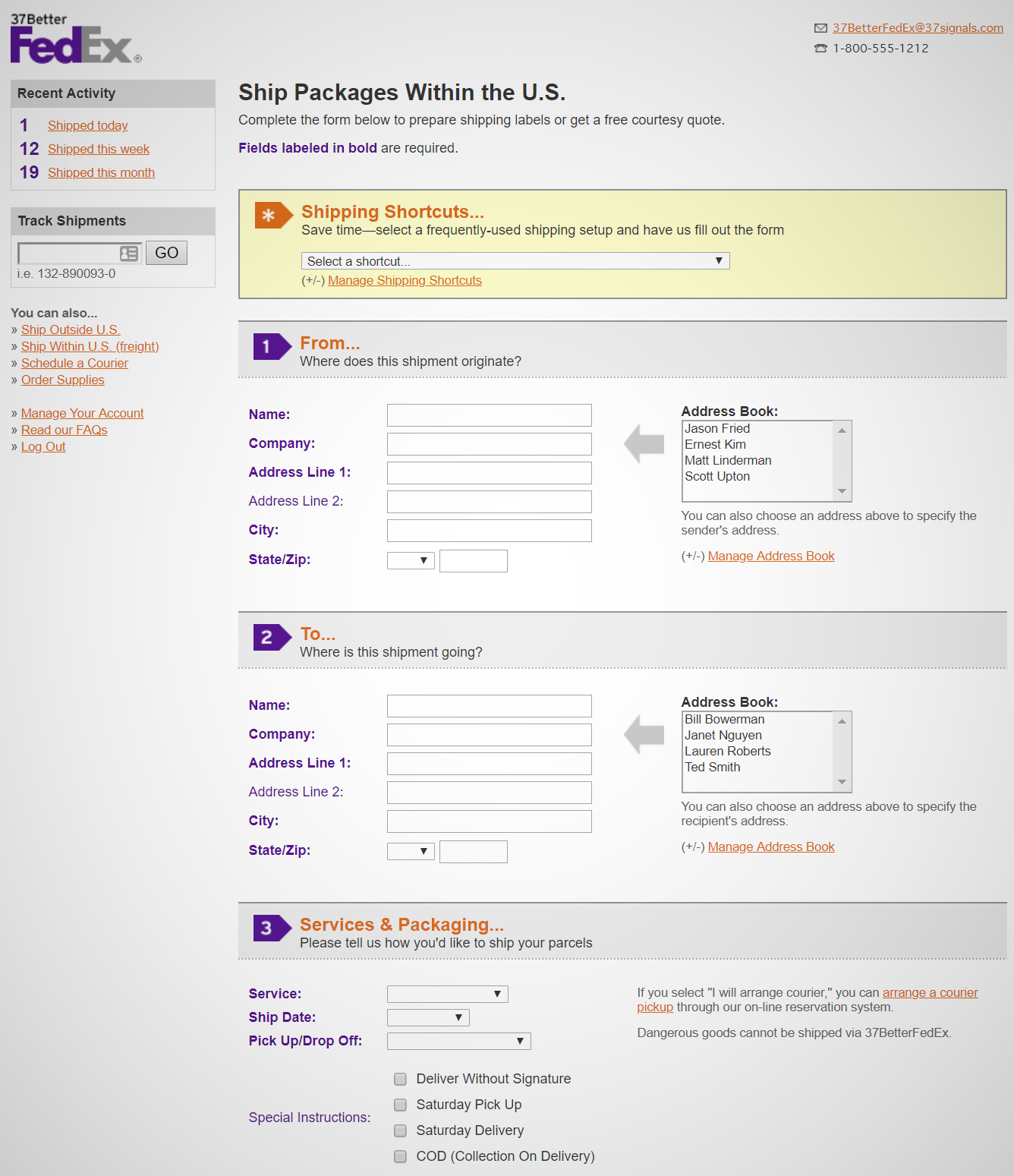

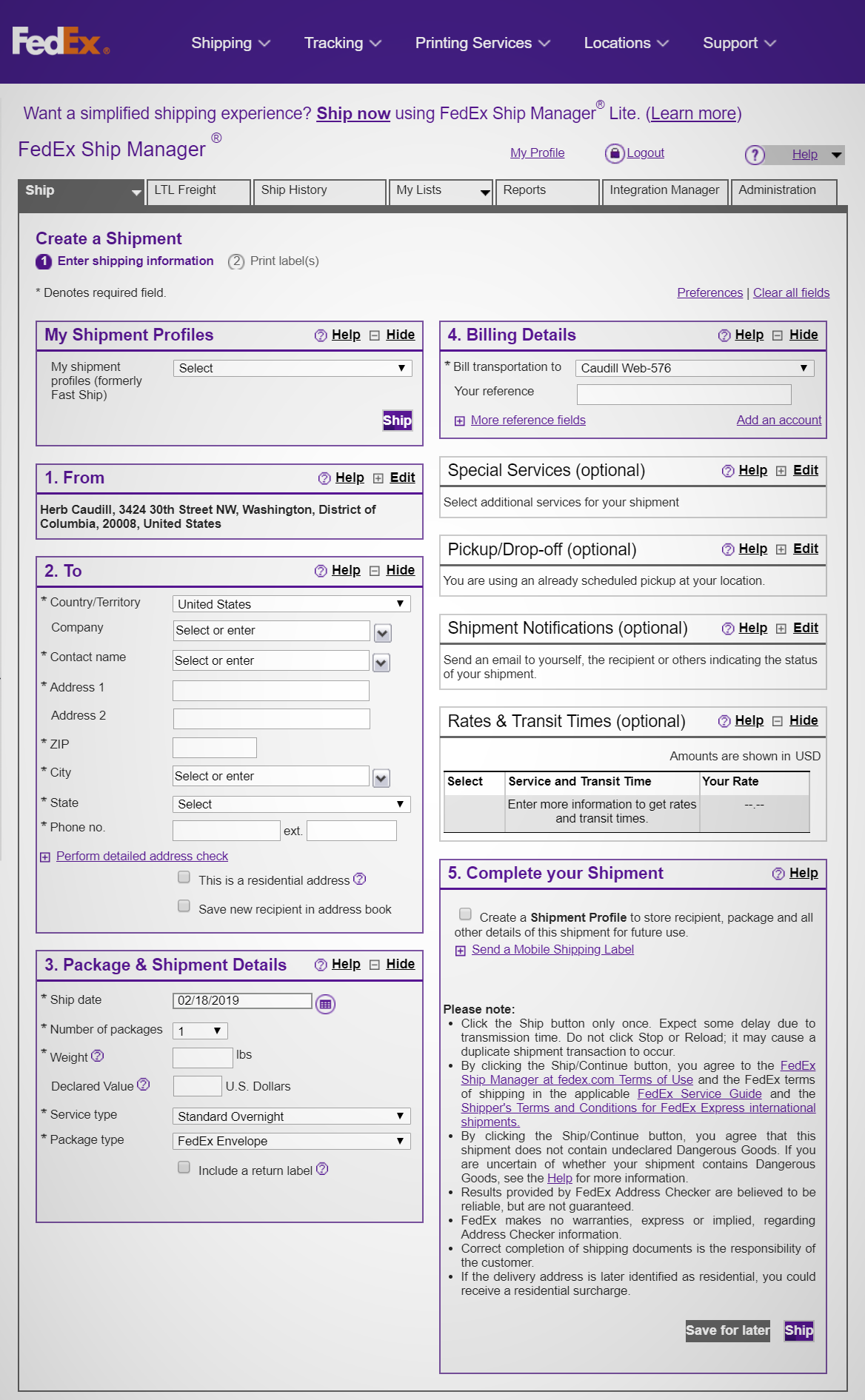

They originally caught my attention when I was just starting out as a web designer, with a series of unsolicited redesigns of sites like Google and PayPal, called 37better.

37signals’ redesign of FedEx’s shipping form (left) is still better than the real thing, nearly two decades later.

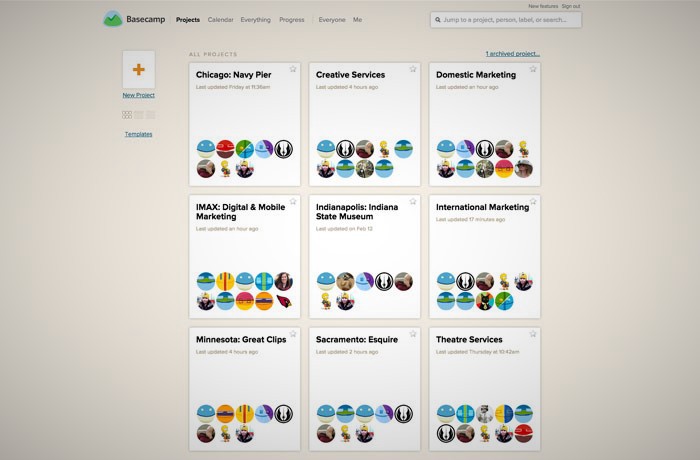

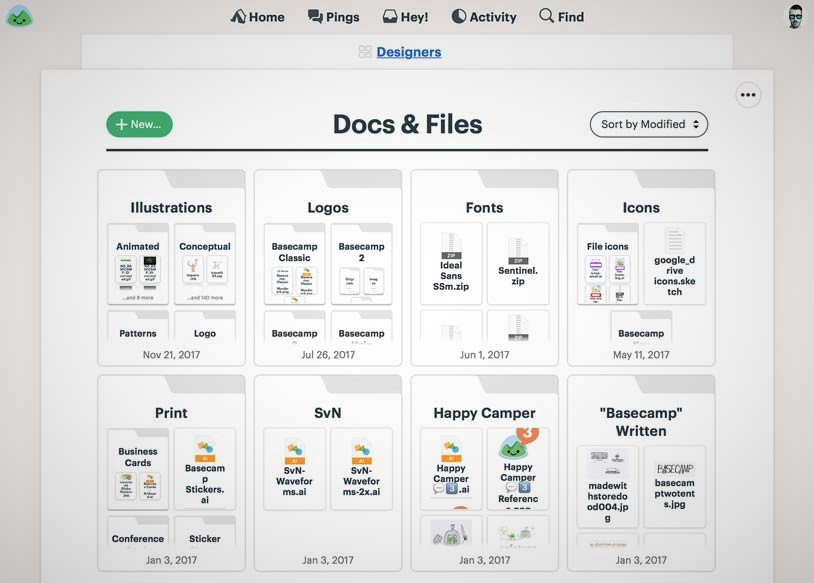

In 2004, they took a project-management tool that they had developed for internal use, and released it as a software-as-a-service product called Basecamp.

This was at a time when subscribing to software was still a novelty. Project management tools came in shrink-wrapped boxes with four-figure price tags and hefty manuals, and were all about modeling critical paths and generating complex Gantt charts.

Basecamp sold for $50 a month and was a breath of fresh air, with its super-simple interface and its focus on communication.

Fast forward a few years, Basecamp has half a million happy users, checks are rolling in every month, and Jason and David are starting to get restless.

I saw David tell this story at the Business of Software conference a few years ago. He said that not only had he been convinced by Joel Spolsky that rewriting software would kill the company, but there was an element of self-righteousness inspired by the Agile movement:

[I was] completely taken in with the idea of transcendent software. … That code is infinitely malleable. That legacy is infinitely valuable. That you can change anything, any piece of software, any piece of code can be rewritten. … If software is hard to change, it is your fault. You’re a bad programmer and you just have to learn to be better.

After what he calls “seven fat years”, though, they were in a bind — and it had nothing to do with technical debt.

Golden handcuffs

They started by noticing in their gut a lack of enthusiasm. Not only were they not motivated to work on their flagship product, but they themselves weren’t using the product as much.

They had lots of ideas about how to make the product fundamentally better, but with hundreds of thousands of people building their workflows around Basecamp, every change they made was disruptive to lots and lots of people. The obstacle to change wasn’t a crufty codebase, it was their users.

Their focus on keeping their existing customer base happy was freezing the product in time, and preventing them from appealing to new customers. This wasn’t an immediate problem for the business, but it posed a long-term threat. DHH used the metaphor of trying to keep a leaky bucket full:

You might be plugging all the holes, you might be fixing all the bugs, you might be upgrading all the features the existing customers are complaining about so that no water escapes — but some water always escapes. Customers move on from their job and they leave your software even if they [love it]. But you can kind of delude yourself that, “Hey, this bucket is more than half full still. That’s just a tiny little hole there seeping out and that’s perfectly natural.” But, if you just keep that on for long enough, the bucket is going to end up empty.

Part of the problem is that you hear all the time from your present customers, but you don’t hear from your future customers:

People who showed up at the Basecamp homepage in 2011 and chose not to buy because our ideas were no longer good enough, how often do you think we were hearing from them? Never. We were hearing from this broad base of existing customers who very much would love us to just keep plugging those little holes.

They started to see their profitable product as a set of golden handcuffs:

The number one thing is just to make sure all the users you already have are still happy. The money just keeps coming in every month, new check, new check, new check. Great. But, you have to stick your arms forward and say, “Okay, I will never change my software again.”

Spoiler alert: They rewrote Basecamp from scratch and it turned out great. It took around a year, and new signups doubled immediately following the release of Basecamp 2.

They did two interesting things that, I think, made this work.

First, they didn’t try to rebuild the exact product they already had — because they had new ideas about how to solve the problems they’d originally set out to solve.

Are we really that arrogant to think that the ideas we had in 2003 were still going to be the very best ideas in 2011? I mean, I’ve been accused of being pretty arrogant, but I ran out of steam on that one in like 2008.

So they presented Basecamp 2 as a completely new product, with no guarantees that it would be backwards compatible with Basecamp Classic. Lots of things were new, other things were gone, and lots of things were just totally different.

That decision gave them a degree of freedom. Freedom is motivating, and motivated human beings get more done.

Not having to support every one of the original product’s use cases also bought them a lot of time. For example, the original Basecamp allowed users to host documents on their own FTP server. Cutting out that feature — and others like it, that might have made business sense at one time, but didn’t any more—made it possible to bring the new product to market in a reasonable amount of time.

Sunset considered harmful

But what about all those hundreds of thousands of existing users? All those people who complain loudly when their cheese is moved?

That brings us to the second interesting thing they did, which was that they didn’t sunset their existing product.

David riffed for a while on the notion of “sunsetting” software:

Someone somewhere came up with this beautiful euphemism called the sunset. … Let’s call killing software “sunsetting”. … All the users can sit on the beach and they can watch all their data fade away. It’s going to be beautiful!

The only people who believe in the “sunset” are the people who call it the “sunset”. No user who’s actually ever been through a period of sunset actually comes back and says, “Oh that was beautiful.” They come back and say, “Fuck! I put in years of work in this thing! … And now you’re going to sunset me?”

He points out that when you force users to pack up and move, that’s when you’re making “the worst strategic mistake ever”: Because you’re taking your entire recurring customer base and making them think about whether they want to keep using your software or move to something else altogether.

“Is Basecamp even actually the thing I want anymore? If we have to move all our crap over anyway, maybe I can just move it somewhere else. If I have to pack it all up into boxes and load it on the truck, I can just send that truck across town instead. That’s not a big hassle. The big hassle is to pack up all my shit. Whether it goes to Basecamp again or it goes somewhere else, that’s not the big decision.”

David compares Basecamp Classic to a Leica M3: It hasn’t been manufactured since 1967, but Leica is still committed to supporting it and repairing it for as long as they’re in business. (Photo Dnalor 01)

Instead, Basecamp committed to “honoring their legacy”: They made it easy for people to upgrade, but didn’t require them to leave Basecamp Classic. Not only that, but they’ve committed to continuing to host, support, and maintain Basecamp Classic indefinitely.

The kicker is that, four years later, they did it all over again: Basecamp 3 was released in 2015, rewritten from the ground up, with some features cut, some added, and lots of things changed. And just as before, users of older versions can easily upgrade — but if they prefer, they can continue using Basecamp Classic or Basecamp 2 “until the end of the internet”.

Basecamp 3 is not going to sunset anything. Not the current version of Basecamp, not the classic, original version of Basecamp. Either of those work well for you? Awesome! Please keep using them until the end of the internet! We’ll make sure they’re fast, secure, and always available.

But, but, but isn’t that expensive? Isn’t that hard? What about security? What about legacy code bases? Yes, what about it? Taking care of customers — even if they’re not interested in upgrading on our schedule — is what we do here.

Lessons

Personally, I find this model really inspiring.

Each rewrite allowed Basecamp to revisit design decisions and build the product they wished they’d built the previous time.

For users, this is the best of both worlds: People who don’t like change don’t get their cheese moved; but people who are bumping against your product’s limitations get to work with a new and, hopefully better thought-out application.

Having to maintain multiple versions of product indefinitely doesn’t come without a price; but as David says:

It’s not free. Why would you expect it to be free? It’s valuable, so of course it’s not free. But it’s worth doing.

3. Visual Studio and VS Code

VS 97 -> 6.0 -> .NET -> ... -> 2015 -> 2017 -> 2019 ------- ->

📝VS Code ------😎------- ->

Key: 😎 = street cred

Microsoft made VS Code in order to reach out to developers working on other platforms.

You have to remember that for a long time, working in Microsoft’s world was an all-or-nothing proposition. If you used Visual Studio, you worked in .NET, and vice versa. This split the software community into two big, mostly mutually exclusive camps — to everyone’s detriment.

Reaching out to the cool kids

That started to change even in the Steve Ballmer years— remember what a huge deal it was when the ASP.NET team decided not to reinvent jQuery!

It’s become one of CEO Satya Nadella’s principal missions for Microsoft to explicitly appeal to developers outside its walled garden.

But as Julia Liuson, VP of Visual Studio puts it in this episode of The Changelog podcast:

We didn’t have anything for this whole class of developers — modern, webby, Node-oriented developers, JavaScript — we had nothing to talk to you about. You were a developer we were never gonna be able to attract, at all.

So the motivation for VS Code was to break down that barrier and say “Actually, you know what? We do have something that you could use.”

Visual Studio is a heavyweight product in every sense: It can take upwards of half an hour to install. It has to support a wide variety of complex use cases relied on by enterprise customers. So it wouldn’t have made sense to use Visual Studio itself as a starting point, for Microsoft to try to appeal to other platforms by adding features. And presumably the idea of making Mac or Linux versions of Visual Studio was a non-starter.

So Microsoft started from scratch with no guarantees of backwards compatibility.

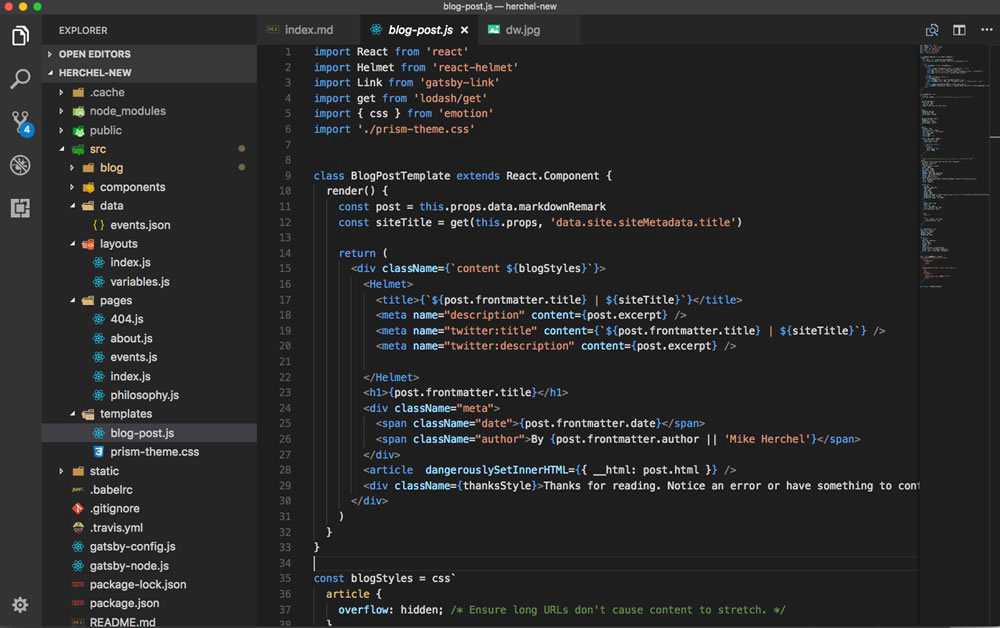

Not quite from scratch, actually: Microsoft already had some important parts lying around, such as the in-browser Monaco editor. And because VS Code is a Node.js app (written in Typescript and run in Electron), they were able to take advantage of the rich JavaScript ecosystem.

VS Code is open-source, lightweight, fast, and extensible; and — amazingly for a Microsoft product — it’s become the coding environment of choice for the cool kids.

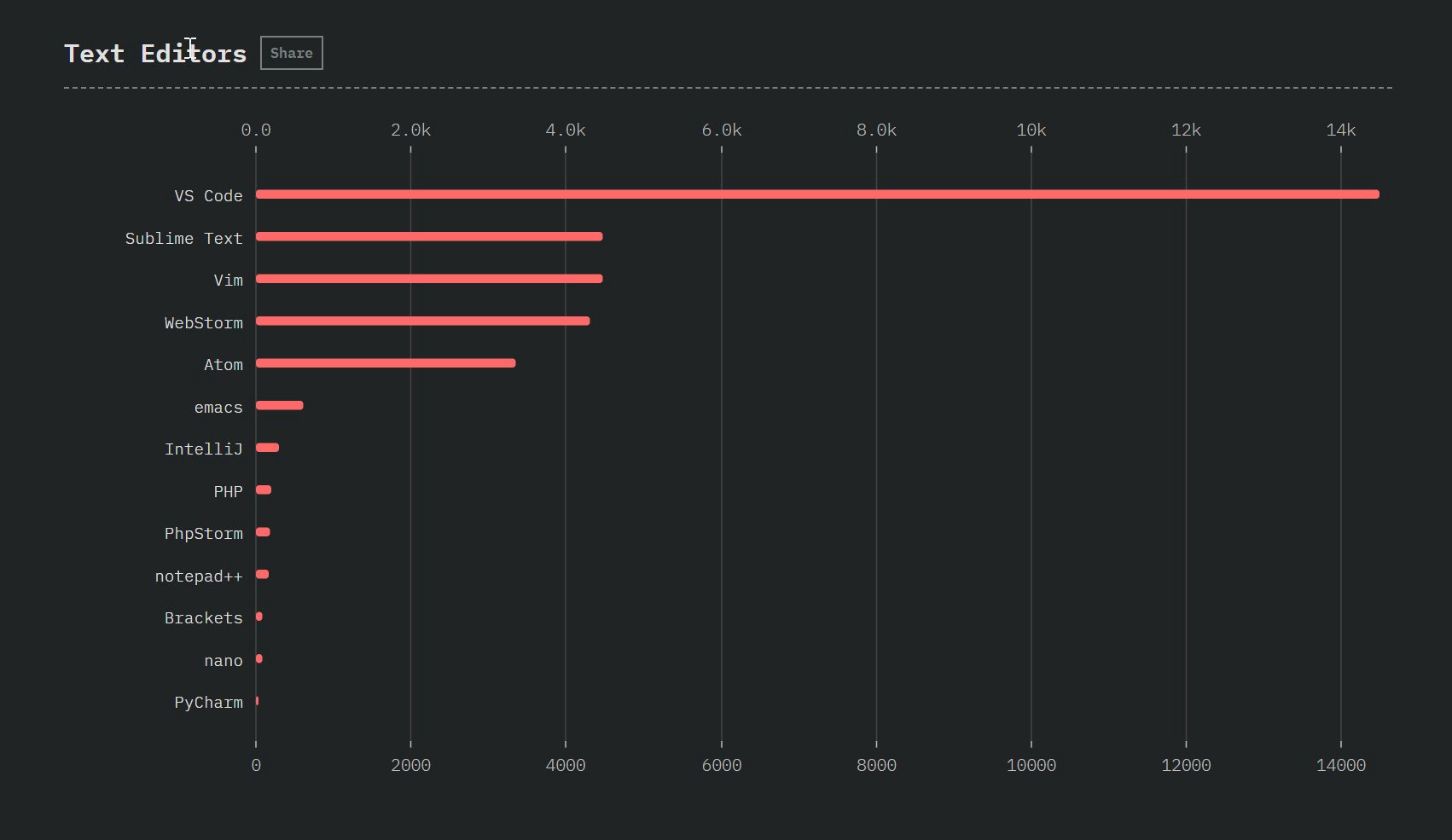

VS Code has become the text editor of choice for JS hipsters. (Chart from State of JavaScript Survey, 2018)

Both products are still actively developed, and there’s no indication that Microsoft intends to sunset Visual Studio.

Lessons

In stark contrast to Netscape’s experience, Microsoft succeeded in building an active open source community around VS Code. This community has multiplied the efforts of the in-house development team.

Of all the open source projects on GitHub, Visual Studio Code is ranked thirteenth by number of stars — coincidentally, just below Linux!

Of course, not everyone has a business model that will support completely open sourcing their core product.

But if open source is a part of your development strategy, it might be worth comparing these two case studies to find out what Microsoft did so differently that caused this community to flourish.

Another multiplier: Microsoft also equipped VS Code with a solid extensibility model, and as a result nearly 10,000 extensions have been written by the community.

One final takeaway from the VS Code story is that things have changed fundamentally in the last few years, in a way that makes it easier than ever to prototype and create software.

In spite all of the hand-wringing about the complexity of today’s toolset, the fact is that the JavaScript ecosystem has evolved over the last few years into the long-awaited promised land of reusable, modular open-source code. In that respect, this is a historically unprecedented time.

4. Gmail and Inbox

Gmail ----------------------------------------------------- -> 📝Inbox for Gmail ------ ↗ -- ↗ -- ↗ 🌇

Key: 🌇 = sunset

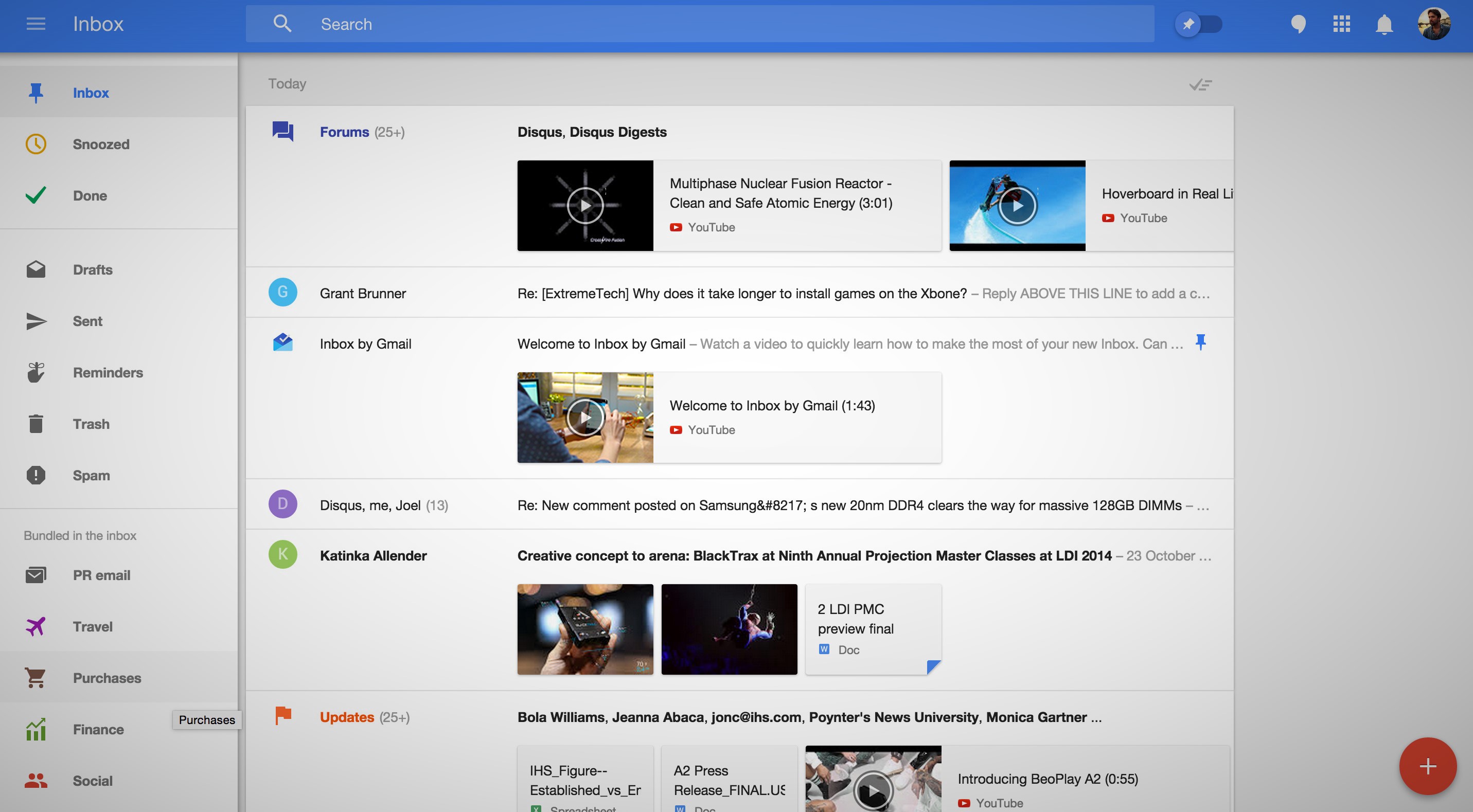

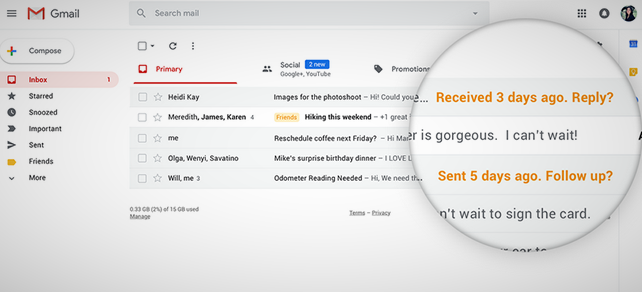

Inbox for Gmail was originally introduced as a stripped-down alternative UX for Gmail “designed to focus on what really matters”. It never approached feature parity with the original Gmail, and it introduced new features like bundles, pinned emails, and snoozed messages.

Some people, including me, adopted Inbox enthusiastically. I always assumed that Inbox was a preview of what Gmail would eventually become, and put up with the lack of some of Gmail’s niceties with the expectation that they’d eventually make it over to Inbox.

Two interfaces, one service

Both Inbox and Gmail used the same back end. They were essentially just different user interfaces for the same service, and you could switch back and forth at will. This had advantages and disadvantages: If Inbox was missing a feature (say, vacation autoresponders) you could always go back to Gmail and do what you needed there. But there was some inevitable weirdness when switching back and forth.

After a while, though, Inbox stopped improving, and it became clear that Google was no longer investing any resources in it. Sure enough, four years after it was launched, Google announced that it would be sunsetting Inbox.

I was initially very annoyed, but after spending a little time with the latest version of Gmail, I found that many of my favorite features from Inbox had been ported to the original product: Smart Reply, hover actions, and inline attachments and images. Gmail’s multiple inboxes were a good-enough stand-in for Inbox’s bundles.

But not everything made it over: Snoozing, for example, became a critical part of how many people dealt with email; and the demise of Inbox left them high and dry.

Lessons

Inbox gave the Gmail team a way to experiment with features without disrupting workflows for the vast majority of users who didn’t choose to switch over.

By committing to having both versions use the same back end, though, Gmail put hard limits on their own ability to innovate.

Google got a lot of criticism, yet again, for shutting down a popular service. Of course, Google discontinues products all the time, so what did we expect.

In this case, Google’s original messaging around Inbox led us to believe that we were getting an early look at the future of Gmail. As DHH would say, this was not a beautiful sunset; for many people it sucked to have to go back to the old product, and lose Inbox’s innovative workflows.

I think there would have been less unhappiness if Gmail had gone all the way to feature parity with Inbox before it was shuttered.

5. FogBugz and Trello

FogBugz ------------------------------------ 😟

📝Trello --------------------------- -> 🤑

Key: 😟 = sad decline 🤑 = money money money

FogBugz is a particularly interesting case, since it was Joel Spolsky’s product: It gives us a look at how the never-rewrite principle plays out with a real-world product.

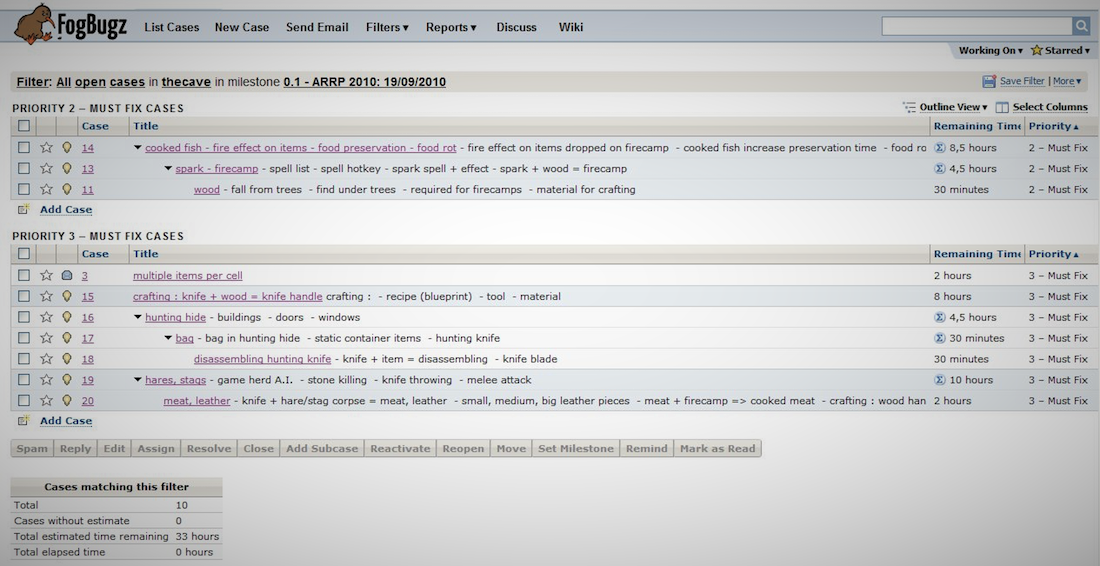

Before there was Jira, before there was GitHub Issues, there was a web-based bug-tracking product called FogBugz. Released in 2000, it was the first product of Fog Creek Software, the firm Joel had recently founded with Michael Pryor; and it was their flagship product for more than a decade. They initially only sold it as shrink-wrapped software to be installed on your own servers, but later came out with a hosted, subscription version.

It became very popular, especially among the kind of developer who, like me, followed Joel’s blog and took his advice to heart. My company used it for many years; it was a great product for its time.

FogBugz was originally written in classic ASP, which ran on Windows servers. When ASP.NET came out, Joel explained why he was in no hurry to upgrade.

In order to allow people to install FogBugz on Linux servers, an intern wrote a compiler, named Thistle, to convert classic ASP to PHP. By 2006 Thistle had evolved into a private home-grown language called Wasabi that compiled to ASP, PHP, and client-side JavaScript.

The strange story of Wasabi

Now developing an in-house, proprietary programming language and compiler is — let’s just say it’s an eccentric choice. So bear with me on a brief detour.

At one point Joel described Wasabi in an off-hand paragraph at the end of a blog post. Apparently some people thought he wasn’t serious, and he clarified that he was. This caused fellow blogger Jeff Atwood’s head to explode:

Writing your own language is absolutely beyond the pale. It’s a toxic decision that is so completely at odds with Joel’s previous excellent and sane advice on software development that people literally thought he was joking.

Joel maintained that it all made business sense: Of course you wouldn’t invent your own language if you were starting from a clean slate. But if you look at each decision along the way, considering the technological context at the time and the codebase they had at the time, you can see how you would end up there.

Reflecting on Wasabi in a thoughtful essay titled “Technical Debt and Tacking Into the Wind”, former Fog Creek engineer Ted Unangst compares the process to traveling without a map:

Imagine you’re in Savannah, Georgia and you want to go to London, England. You don’t have a map, just a vague sense of direction. … You can’t go in a straight line, at least not without building a boat, because there’s an ocean in the way. But there’s a nice beach leading northeast, which is in the direction you want to go. Off you go. Time passes. You notice you’re not heading directly to your destination, but with each step you take, you are getting closer.

Somewhere around Boston, or maybe Nova Scotia, you finally stop and think about your choices. Maybe this isn’t the way to London. From high above in the peanut gallery, you can hear the cackles. “Hahaha, look at these retards. Can’t tell the difference between England and New England. Get these fools a map.” But that’s just the thing; you didn’t have a map. Maps are made by people who, almost by definition, don’t know where they’re going.

At any rate, as Jacob Krall, another former Fog Creek developer, explains, this decision traded off developer velocity today for maintainability tomorrow — the definition of technical debt — and by 2010 the bill for this debt was starting to come due.

We hadn’t open-sourced [Wasabi], so this meant any investment had to be done by us at the expense of our main revenue-generating products. … It was a huge dependency that required a full-time developer — not cheap for a company of our size. It occasionally barfed on a piece of code that was completely reasonable to humans. It was slow to compile. Visual Studio wasn’t able to easily edit or attach a debugger to FogBugz. … All new hires had an extensive period of learning Wasabi, regardless of their previous experience. … What’s more, we weren’t living in a vacuum. Programming languages were of course improving outside of Fog Creek. … Developers began to feel like their brilliant ideas were being constrained by the limitations of our little Wasabi universe.

An inflection point

At this point, a decade in, FogBugz was a mature and stable product. Joel had created Stack Overflow as a side project with Jeff Atwood (presumably his exploded head had had time to heal by then).

FogBugz wasn’t setting the world on fire, and it was showing its age. While the market for bug trackers was still fragmented, Atlassian’s Jira — which had come out a couple of years after FogBugz — had become the default choice, especially for bigger enterprise users.

I’m a little fascinated by this particular inflection point in Fog Creek’s history. Like Basecamp, they had a profitable, mature product. It was no longer sexy, and probably not very exciting to work on. It embodied, for better and for worse, years of technological shifts and evolving ideas about how to solve a specific problem space.

One response, of course, would have been to do as Basecamp did: Take everything Fog Creek had learned about bug tracking, and reinvent FogBugz, starting from a clean slate.

I’m guessing this idea didn’t go very far— “things you should never do”, “worst strategic mistake”, etc. etc.

I recently came across an article from 2009, when Joel was writing a monthly column for Inc. Magazine. This column, titled “Does Slow Growth Equal Slow Death?”, has a very different tone from his usual self-assured bombast: It’s introspective, tentative, doubtful. He frets about Atlassian’s rapid growth — wondering if in the end there’s only space for one product in the bug-tracking market.

I had to wonder. We do have a large competitor in our market that appears to be growing a lot faster than we are. The company is closing big deals with big, enterprise customers. … Meanwhile, our product is miles better, and we’re a well-run company, but it doesn’t seem to matter. Why?

So he resolves to do two things. First, add All The Features to FogBugz:

That’s the development team’s mission for 2010: to eliminate any possible reason that customers might buy our competitors’ junk, just because there is some dinky little feature that they told themselves they absolutely couldn’t live without. I don’t think this is going to be very hard, frankly.

Second, build up an enterprise sales force. Joel confesses that this is something that he’s not good at, and finds distasteful.

I don’t know how either of those two plans played out. The last time Joel ever mentioned FogBugz on his blog was a perfunctory announcement of a minor release a few months later.

A new hope

What did happen was this:

Around the time of Fog Creek Software’s ten year anniversary, I started thinking that if we want to keep our employees excited and motivated for another ten years, we were going to need some new things to work on.

So they split up into teams of two, with each team working to come up with and prototype a new product idea.

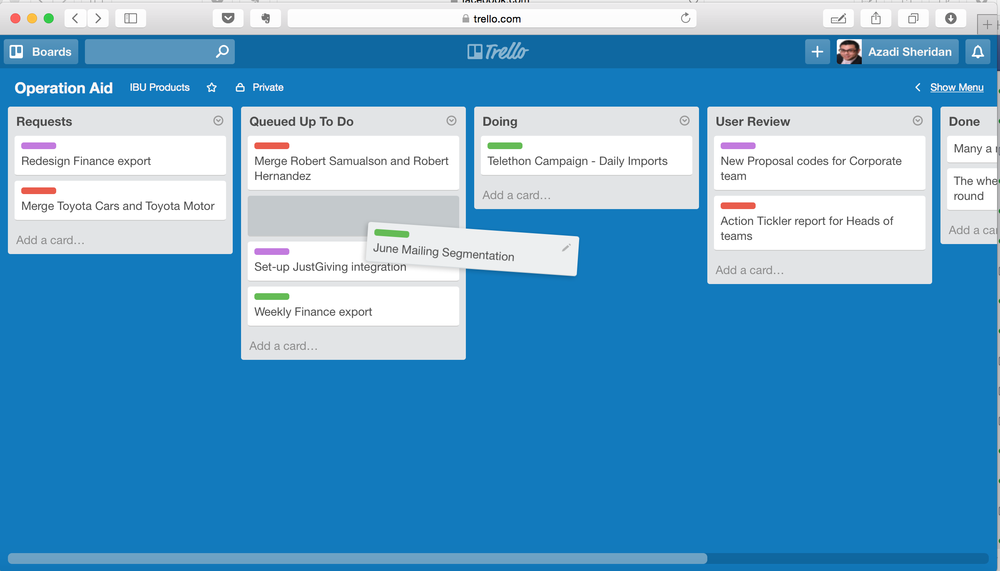

The winning idea was inspired by the Kanban board — a physical tool, often used in software development, generally involving Post-It notes distributed across columns on a whiteboard.

Joel presented it as a tool for managing work at a higher level than FogBugz allowed:

Honestly, with all the fancy-schmancy “project management” software out there, I never found a way to keep track of who’s supposed to be working on what. … As the founder of two companies it was starting to get distracting to walk down the hallways seeing dozens of people getting paid to sit at computers … and I had no idea if they were doing the exact right thing, or maybe something they thought was important but which, nevertheless, was not, actually, important.

In building Trello, Fog Creek’s developers got a chance to use contemporary technologies, for a change:

We use cutting edge technology. Often, this means we get cut fingers. Our developers bleed all over MongoDB, WebSockets, CoffeeScript and Node. But at least they’re having fun. And in today’s tight job market, great programmers have a lot of sway on what they’re going to be working on. If you can give them an exciting product … they’ll have fun and they’ll love their jobs.

Trello also multiplied their in-house development team’s efforts by enabling third-party plug-ins from the beginning:

The API and plug-in architectures are the highest priority. … Never build anything in-house if you can expose a basic API and get those high-value users … to build it for you. On the Trello team, any feature that can be provided by a plug-in must be provided by a plug-in.

Programmers, of course, saw the utility of Trello right away; but there was nothing in the tool that was specific to software development. Joel described it as useful for “anything where you want to maintain a list of lists with a group of people.” Trello was soon being used to organize everything from weekly meals to weddings to animal shelters.

Where FogBugz was a vertical product — targeted at a specific niche market — Trello was a horizontal product, that could be used by anyone for anything. Joel argues that “going horizontal” was the right thing to do for FogBugz at this juncture:

Making a major horizontal product that’s useful in any walk of life is almost impossible to pull off. You can’t charge very much, because you’re competing with other horizontal products that can amortize their development costs across a huge number of users. It’s high risk, high reward: not suitable for a young bootstrapped startup, but not a bad idea for a second or third product from a mature and stable company like Fog Creek.

In order to scale up quickly to lots and lots of users, Trello was initially offered for free. A paid “business class” plan was introduced later.

In 2014, Trello was spun out into a separate company. Three years later, with over 17 million users, Trello was sold for $425 million. In an ironic twist, the buyer was Atlassian, Fog Creek’s old nemesis.

Meanwhile back at the ranch…

Fog Creek went on to develop yet another new product, a collaborative programming environment first called HyperDev, then GoMix, and finally renamed to Glitch.

In the meantime, FogBugz languished in obscurity. In 2017 someone decided that FogBugz was a dumb name, and engineering efforts went into re-branding the product as Manuscript. A year later — just a few months ago — Fog Creek sold the product to a small company called DevFactory, which immediately changed the name back to FogBugz.

Under CEO Anil Dash, Fog Creek became a single-product company and changed its name to Glitch.

Lessons

I have a lot of feelings about all of this.

Making a nice place to work was our primary objective. We had private offices, flew first class, worked 40 hour weeks, and bought people lunch, Aeron chairs, and top of the line computers. We shared our ingenious formula with the world: Great working conditions → Great programmers → Great software → Profit!

The key to understanding this whole story is that Fog Creek was never about bug tracking as much as it was about a empowering programmers — starting with their own:

With this “formula” in mind, maybe we can put together a coherent and encouraging narrative: Fog Creek built a business around developer happiness. This was reflected both in the company’s products and its internal “operating system”. Its first product, a bug tracker, provided a foundation for launching a new product that solved a similar problem in a more broadly applicable way.

I think it’s really telling that Trello’s origin story, the way Joel tells it, is not so much Joel looking for a new business opportunity, as it was Joel looking for a way to keep Fog Creek’s developers happy and engaged. Creating a product worth half a billion dollars, that was just a pleasant unintended consequence.

I can’t help but be a little sad about the way things ended up for FogBugz, though. I don’t imagine there was a lot of developer happiness going on during the product’s final days at Fog Creek.

Clearly all the people involved had bigger fish to fry: Stack Overflow, Trello, and Glitch are each individually far more useful and valuable than FogBugz could ever be; and any given person can only do so much with their time. So I can’t begrudge anyone in particular for losing interest in FogBugz, with its two-decade-old codebase and its competitive niche market. And at least its loyal users found a good home, and didn’t get the “sunset” treatment!

But the sentimental part of me wishes there had been a better way to “honor the legacy” of all the people who created it and used it over all those years.

6. FreshBooks and BillSpring

FreshBooks ------------------------------------------------ ->

🕵️📝BillSpring ------- ↗

Key: 🕵️♀️ = undercover operation

This has already turned into a much longer article than I ever imagined, but I can’t leave this story out. Stick with me, it has a great twist.

Stop me if you’ve heard this before

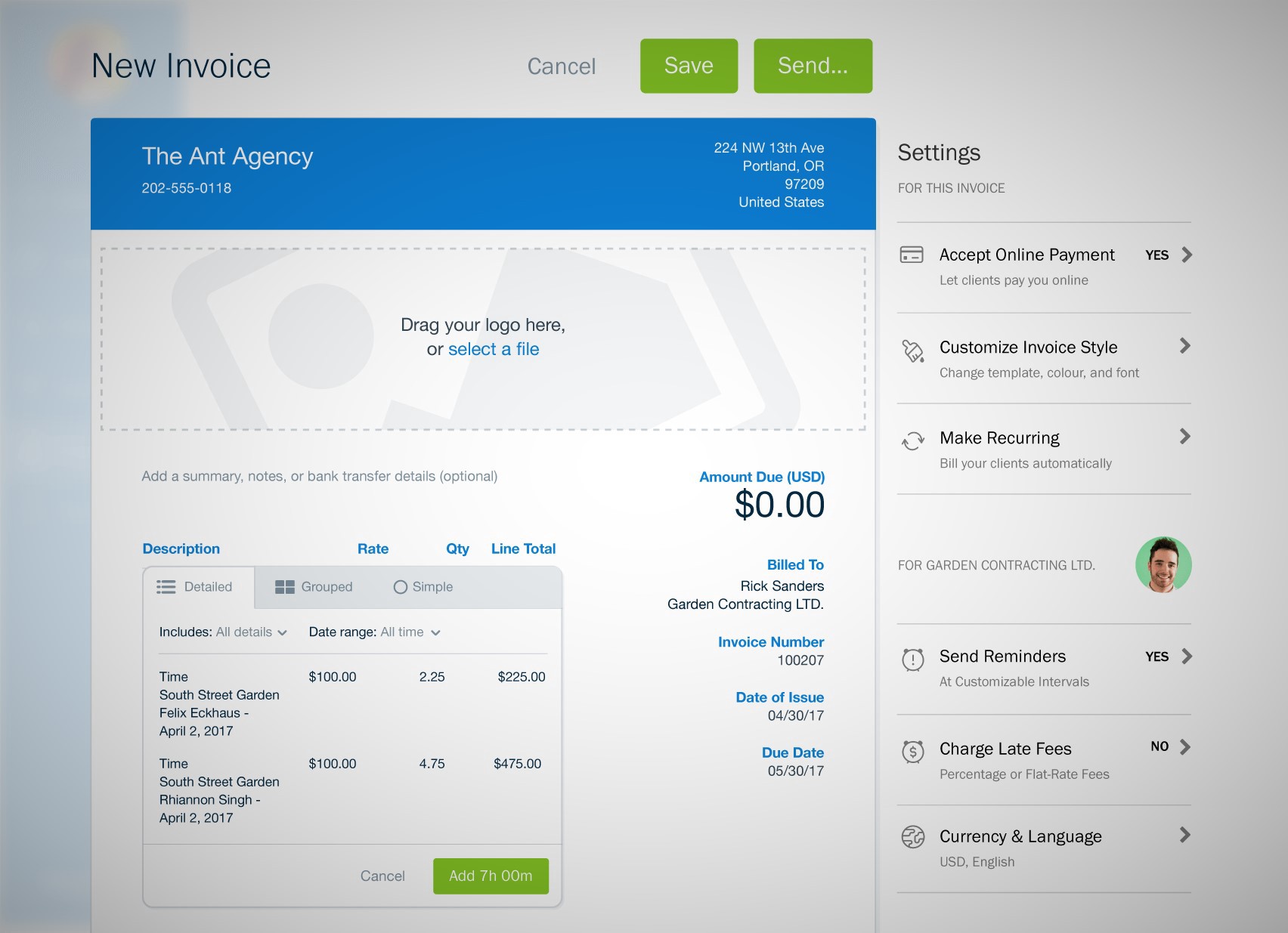

In the early 2000s, Mike McDerment owned a small design agency. He was using Word and Excel to make invoices, having decided that accounting software was too complicated for what he needed.

This system was good enough until it wasn’t: Mike was a designer, not a programmer, but he and two co-founders managed to cobble together a tool good enough for a few people to pay $10 a month to use it. It took nearly four years for the business to make enough for him to move out of his parents’ basement.

I hit my breaking point one day when I accidentally saved over an important client invoice — I just kinda snapped. I knew there had to be a better way, so I spent the next two weeks coding what would become the foundation of what is now FreshBooks.

By the product’s 10-year anniversary (is this starting to sound familiar?) FreshBooks was solidly profitable, with more than 10 million users and 300 employees.

Just one problem: By the time they managed to hire “real” programmers, they had a million lines of “founder code”. An outside analyst reviewed their codebase and concluded:

“The good news is that you’ve solved the hardest problem. You’ve figured out how to build a business, and you have a product that people love. The bad news is that you guys stink at technology.”

More importantly, though, they had new ideas that the existing product wouldn’t accommodate:

We started the company more than a decade ago; the world has changed and we’ve learned a lot about building products and serving people who work for themselves. While self-employed professionals and their teams are a massive and growing part of the labor force … For FreshBooks to be able to keep pace and to serve that group well in five years’ time, we knew we needed to act.

McDerment had absorbed the conventional wisdom about starting from scratch:

There’s no greater risk for a software company than rewriting. Chances are you won’t even finish the project. It will take longer than you think. It will cost more. When you do it, the customers could like it less. And there are no guarantees that by building a new platform it’s a better product. The number one rule in software is you don’t re-platform your software.

So they made a couple of attempts to clean up the mess without starting over; but found it impossible to “change tires on a moving vehicle”.

What happened next may surprise you

The idea that McDerment finally hit on was to secretly create a “competitor” to FreshBooks.

He incorporated a completely new company, named BillSpring, in Delaware. The new company had its own URL and its own branding and logo. Careful to keep the two companies from being linked, he had an outside lawyer draft new terms of service.

The development team adopted the book Lean UX: Designing Great Products with Agile Teams by Jeff Gothelf and Josh Seiden as their guidebook, and put in place Agile practices like scrum teams and weekly iterations with review sessions with real customers. McDerment told them to think of themselves as a startup and himself as their venture capitalist:

“You’ve got four and a half months. If you’re in the market by then, we’ll give you more money. Otherwise, we’re out.”

When the first year was up, they started charging BillSpring customers. At one point the new product was validated in an unexpected way:

The team managed to come up with an MVP a few days before the deadline. They bought Google AdWords to send traffic to the new site. They offered free accounts for the first year. Before long they had actual users, and they started iterating quickly to polish the product.

“One person called us to cancel FreshBooks to tell us they were going to this new company,” McDerment says. “That was a good day.”

Shortly afterwards they lifted the veil of secrecy: They let BillSpring customers know that the product was now FreshBooks, and let existing FreshBooks customers know that a new version would soon be available.

Little by little, “FreshBooks Classic” customers were invited to try the new upgrade — but they didn’t have to, and they could always migrate back to the more familiar version if they wanted.

Lessons

FreshBooks’ undercover rewrite didn’t come cheap: McDerment estimates that they spent $7 million on the project. After more than a decade of bootstrapped growth, they had just raised $30 million in venture capital; so they had the cash. Not everyone has that much money to spend.

Forbes estimates that FreshBooks had $20 million in revenue in 2013. In 2017, after the upgrade was complete, they earned $50 million. They don’t say how much of that growth came from the new product, but starting over certainly doesn’t seem to have slowed down the company’s growth.

McDerment reports that they’re able to add features more quickly and easily now. More importantly, they’re facing the future with a product that captures their best ideas.

Beyond their stated goals, though, they’ve found that the experience has changed company culture — in a good way. Their time pretending to be a startup has left them acting more like a startup. The “lean” practices they experimented spread to the whole engineering team. Customers are closely involved in new feature development.

FreshBooks went to extraordinary lengths to insulate themselves from the potential downside of a rewrite: By innovating under a throw-away brand, developers felt free to rethink things completely, and to take bigger risks. That way, the worst that could happen was that they’d reach another dead end; at least they wouldn’t damage their existing brand in the process.

It all feels a little extreme, and perhaps it’s not necessary go to the lengths they did. But it’s a reminder of how serious the stakes are.

Some thoughts for now

The conventional wisdom around rewriting software is that you should generally avoid it and make incremental improvements instead — unless that’s truly impossible for some reason.

I agree with this, as far as it goes.

This advice assumes, though, that the objective is to end up with the original product plus some set of new features.

But what if you want to remove functionality? Or what if you want to solve some use case in a completely different way? What if your experience with the product has given you ideas for a fundamentally new approach?

My takeaway from these stories is this: Once you’ve learned enough that there’s a certain distance between the current version of your product and the best version of that product you can imagine, then the right approach is not to replace your software with a new version, but to build something new next to it — without throwing away what you have.

So maybe if you’re thinking about whether you should rewrite or not, you should instead take a look at your product and ask yourself: Should I maybe create my own competitor? If my product is FogBugz, what’s my Trello? If it’s Visual Studio, what would my VS Code look like?

If you re-read Spolsky’s post on Netscape and DHH’s post on Basecamp side by side, you’ll see that they agree on one thing: What you’ve already created has value.

The good news is that you don’t have to throw that value away in order to innovate.